Series: Words of Conviction

Tracing a Junk Science Through the Justice System

Text STORY to 917-905-1223 to get the next installment in this series as soon as it publishes. Standard messaging rates apply.

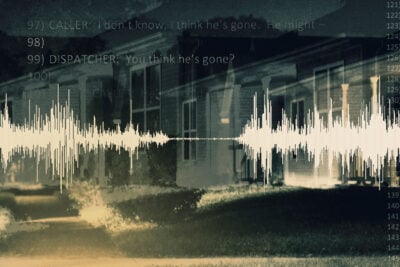

Revelations that a new type of junk science known as 911 call analysis has infiltrated the justice system have triggered calls by prosecutors, judges and defense attorneys nationwide to ban the use of the technique, review past convictions in which it was used and exact sanctions against prosecutors who snuck it into court despite knowing it was inadmissible.

The actions follow a two-part ProPublica investigation published last year that many judges and other court officers said took them by surprise. “I never anticipated that prosecutors — officers of the court — would engage in systematic organized frauds,” a judge in Ohio wrote in an email to ProPublica. She said she had alerted fellow judges to be on the lookout for 911 call analysis, which ProPublica found to be pervasive throughout the justice system: “I’m sure that some will care and share my outrage that innocent people are going to prison.”

The technique’s chief architect, Tracy Harpster, developed a program to spread his methods and says police and prosecutors who take his training will learn how to identify guilt and deception from the word choice, cadence and grammar of those calling 911. So far, researchers who have tried to corroborate Harpster’s claims have failed.

Last year, ProPublica documented more than 100 cases in 26 states where law enforcement has employed his methods. Those responsible for ensuring honest police work and fair trials — including the FBI — have instead helped 911 call analysis metastasize. The investigation revealed that some prosecutors knew 911 call analysis would not be recognized as scientific evidence but still disguised it in trial against unwitting defendants anyway.

During the reporting for the two stories, Harpster at first defended his program but then did not respond to repeated interview requests or detailed lists of questions. Supporters of his work in law enforcement have said 911 call analysis is a valuable investigative tool but not decisive evidence on which to base a conviction.

On Wednesday, he and Susan Adams, who co-authored the original study the technique is based on, sent a letter to ProPublica and argued its coverage had “presented an inaccurate narrative” and listed material they claimed to be omissions and misrepresentations. They asked that their letter be published. ProPublica is also publishing a point-by-point response.

Last October, ProPublica reported on the case of Jessica Logan, a young mother convicted of killing her baby after a detective trained by Harpster testified about his analysis of Logan’s 911 call. Shortly after the story was published, the Supreme Court of Illinois agreed to take another look at Logan’s case.

In addition, attorneys from the Exoneration Project and the Center for Integrity in Forensic Sciences offered to represent her. One of her new lawyers is Josh Tepfer, who was recently profiled by BuzzFeed News for helping exonerate 288 wrongfully convicted people, “making him among the most prolific exoneration attorneys since anyone began keeping track.”

Hope Bradford, who is a mother figure to Logan, said she’s encouraged by the recent developments but is reserving optimism. “I never thought it would even get this far,” she said. “I’m just waiting for her to come home — that’s all.”

Faulty scientific disciplines, including misleading testimony, are the second most common factor in wrongful convictions, according to the Innocence Project. “The criminal legal system can add 911 call analysis to the junk pile of fake scientific theories contributing to this statistic,” said Nellie King, president of the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers. She called the business of 911 call analysis “dangerous and insidious.”

“Most bothersome is the fact that justice agencies — police officers and prosecutors alike — are buying what he is selling,” King added. “Harpster’s impact on case outcomes is devastating to those falsely accused based on his claims.”

North Carolina’s Office of Indigent Defense Services issued a warning to attorneys across the state to be on the lookout for appearances of 911 call analysis. Fair and Just Prosecution, a network of elected prosecutors, called on its members to review past cases, as well: “Prosecutors must guard against these practices and correct the past injustices they’ve caused through post-conviction review processes.”

At a recent summit of prosecutors in Austin, Texas, Miriam Krinsky, the group’s president, presented ProPublica’s reporting to warn new district attorneys about 911 call analysis. In an email, Krinsky said her organization, in partnership with the Innocence Project, “is concerned about this issue and looking at where and how elected prosecutors can engage to guard against these and other practices that undermine the integrity of convictions.”

In recent weeks, dozens of readers, including defense attorneys and prosecutors, have reached out to ProPublica to inquire about the other jurisdictions where 911 call analysis has surfaced.

Reporters canvassed a sample of about 50 departments and training associations nationwide where records show Harpster’s methods appear to have surfaced over the past 10 years. These agencies, which range from Minnesota Bureau of Criminal Apprehension to the Tennessee Bureau of Investigation, have either hosted him for seminars, sent officers to attend, used his methods in actual cases or did a combination of all three.

Eleven of the 50 agencies responded, and the rest did not answer questions about whether or not they’d continue to support Harpster’s work. Those that did reply either distanced themselves from the program or minimized its role in past cases.

“We’ve never been of the opinion that 911 call analysis should be anything more than a potential investigative lead,” Susan Medina, chief of staff with the Colorado Bureau of Investigation, said in an email, adding that the department “would never advocate for 911 call analysis to be a deciding factor of an arrest or conviction.”

Some of those agencies that responded to ProPublica’s survey didn’t know about their past involvement with the program.

For example, Melaney Arnold, a public information officer with the Illinois State Police, said that department leaders were unaware of 911 call analysis or anyone who’s been trained in it. ProPublica then sent her emails and attendance lists documenting personnel who have attended the program or consulted with Harpster.

“Let me circle back with staff,” Arnold replied in an email. “They may have only been looking at 911 call analysis and not the concept in general.”

Two notable agencies that did not respond to questions are the Westchester County, New York, and Orange County, California, district attorneys offices.

A prosecutor in Westchester once wrote to Harpster to thank him for his consultation, which, he said, “proved to be an invaluable aid in understanding the defendant’s 911 call and greatly assisted in the successful prosecution.”

In Orange County, the district attorney charged a woman with murdering her boyfriend 26 years ago. The arrest came last spring, after prosecutors and detectives consulted with Harpster. “It significantly helped our district attorney to realize the indicators of guilt in the phone calls,” the lead detective told Harpster in an email, “as well as suggestions on how to introduce the 911 calls to the jury during trial.”

Public Defenders and Defense Attorneys: Help ProPublica Report on Criminal Justice

Help us tell stories that can make a difference in how the U.S. criminal justice system works.