This article was produced for ProPublica’s Local Reporting Network in partnership with The Press of Atlantic City. Sign up for Dispatches to get stories like this one as soon as they are published.

Last fall, amid the second year of the pandemic, Atlantic City’s casino executives painted a dire picture for New Jersey’s Legislature. Their brick-and-mortar properties were struggling. And despite thriving online gaming businesses, casinos said they were losing most of that revenue to companies that operate the internet gambling sites.

If policymakers didn’t cut casinos’ tax burdens, industry leaders forecast “grave danger” ahead. The state Senate president went further, warning that four of the city’s nine casinos could close.

The pitch worked. Fearing closures and layoffs, legislators moved quickly to deliver tax relief, few questions asked. “All good by me,” said Gov. Phil Murphy, who signed it on Dec. 21, one day after both chambers passed it.

The legislation altered the formula that determines how much casinos pay the city, its school district and the county to operate. And under the changes, companies will collectively pay those entities $55 million less than they otherwise would have this year — cuts that will disproportionately impact Atlantic City, the distressed capital of the state’s gaming industry.

The problem? Although the casinos cried poor, business is back.

As they pushed for tax relief, gaming companies were already on the rebound from the pandemic slump, recording profits above 2019 levels. The casinos’ parent companies were also spending billions of dollars to purchase online gaming companies, acquisitions that will help assure them more revenue from online wagers, according to a Press of Atlantic City and ProPublica review of state and federal financial filings, as well as public statements by casino representatives.

The industry in Atlantic City reported roughly $767 million in gross operating profit in 2021, its best year in more than a decade. But, as a result of the change in the law, it will pay $110 million in a key local tax — the smallest amount in the history of the five-year-old levy and $20 million less than the year before. (See how we calculated casinos' tax burden.)

“How do you do a tax decrease of that magnitude while they’re registering those kinds of profits on their books?” said Jim Kennedy, former executive director of the Casino Reinvestment Development Authority, the state agency that oversees the investment of gaming tax revenue for economic development projects.

The debate centers around a taxing program known as PILOT, or payment in lieu of property taxes. The plan was adopted in 2016 to resolve the costly fights that casinos waged with Atlantic City to dispute their property assessments, battles that nearly bankrupted the city. Instead, each casino now pays a share of an industrywide assessment calculated based on the prior year’s total gaming revenue. Since the system was implemented, Atlantic City has received the largest share of PILOT, with payments making up about a third of the city’s annual budget. But this year, the casino companies didn’t want to see their PILOT levies rise, in part because a separate tax break was simultaneously expiring.

The upturn in business for the casinos contrasts sharply with the reality of Atlantic City, which has been struggling to emerge from near financial ruin since 2016, when New Jersey imposed a state takeover. This year, at a time of high inflation and rising costs, the city of 38,000 estimates it will get $91.7 million from local taxes on casinos, $5 million less than it did last year. That might not sound like a lot of money for a city, but leaders had expected this year’s casino tax revenues to rise compared to last year. In fact, had lawmakers not changed the tax law, Atlantic City would have seen $133 million this year — $41 million more than the city is actually getting, according to state and city projections.

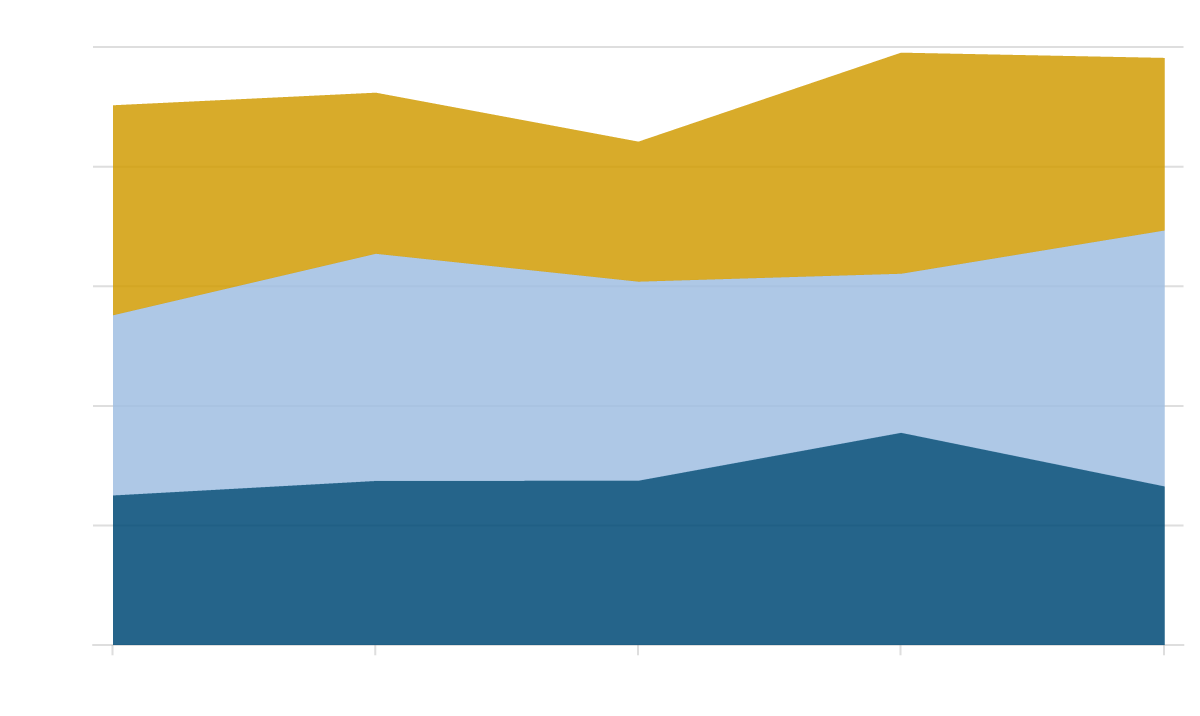

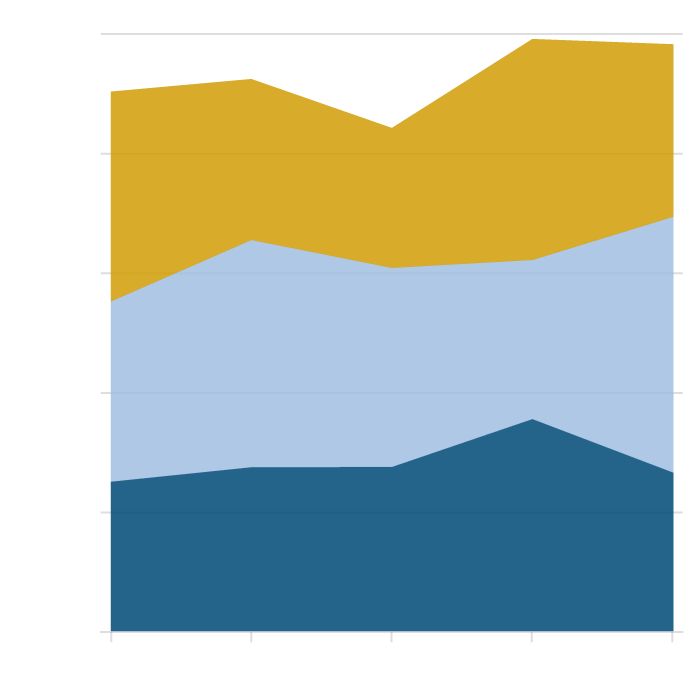

Casino PILOT Payments Are a Big Part of Atlantic City’s Budget

$250M

200M

County, state and federal revenue

150M

Other local revenue

100M

50M

PILOT payment

0

2017

2018

2019

2020

2021

250M

200M

County, state and federal revenue

150M

Other local revenue

100M

50M

PILOT payment

0

2018

2017

2019

2020

2021

And by most metrics, Atlantic City needs the cash.

More than a third of its residents, who are mostly Black and Hispanic, live in poverty. Its infant mortality rate is alarmingly high, and its children have higher levels of lead in their blood than kids almost anywhere else in New Jersey, according to the most recent state reports. In the shadow of the gleaming casino towers that dot its famous four-mile boardwalk lies a single full-service grocery store.

Atlantic County, which has one of the highest foreclosure rates in the nation, could also feel the pinch. The new tax formula will result in approximately $19.3 million less than expected coming to the jurisdiction over the next five years, county estimates show. County officials, who are suing the state to maintain their share of tax revenue, say the reduction will hinder several public health programs and services for veterans, seniors and disabled residents.

For its part, the industry defends the new law.

In response to our reporting, Joe Lupo, head of the Casino Association of New Jersey and president of Hard Rock Hotel & Casino Atlantic City, said the soaring revenue figures give a distorted picture of the industry’s health because its online partners get a large chunk of the money from internet gaming. “Failing to adjust the PILOT would have resulted in egregious, inappropriate, and inequitable taxes for any industry, let alone an industry that is still fighting to recover from COVID-19,” the group said in a statement.

The industry’s most recent financial reports, released by state regulators last month, show revenue from in-person gambling has surpassed pre-pandemic levels.

MGM Resorts International, the parent company of the Borgata Hotel Casino & Spa, the market leader in Atlantic City, also defended the changes to PILOT. “We take our position as a large employer and community leader seriously and have devoted significant efforts and resources to Atlantic City’s economic success and future,” a spokesperson said in a statement. “Our priority when it comes to taxation is ensuring it’s structured so that each operator is contributing its fair share.”

Former state Sen. Steve Sweeney, the South Jersey lawmaker who led the legislative push last year, stood by his actions. “Casinos would have closed,” he said in an interview. “We did the best we could in a bad situation. We saved Atlantic City, we got it back on its feet.”

Murphy, through a spokesperson, declined to comment.

For local and state officials, though, the new PILOT law has renewed questions in a long-running debate about whether Atlantic City is being shortchanged, despite policymakers’ promises from more than four decades ago that legalized gambling would help revitalize the beleaguered community.

“There is a difference between being a good partner and getting taken advantage of,” said City Councilman Jesse Kurtz, a Republican representing the 6th Ward, who opposed the legislation.

A New Tax System for Atlantic City

Since the first New Jersey casino opened in Atlantic City in 1978, the city’s fortunes have been tied to gaming. The industry expanded rapidly, growing to a dozen properties, nearly all along the city’s world-famous boardwalk, and recording year-over-year gains for nearly 30 years. Taxes on casino operations, as well as related fees, sent billions to the state. Money also flowed directly to Atlantic City in two other forms: property taxes, which became the single largest source of municipal revenue, and another tax dedicated to financing community projects. The latter levy, known as the investment alternative tax, or IAT, was created in 1984 to ensure the industry invested in Atlantic City amid concerns that casinos were bilking the city.

But, over the past decade and a half, a slew of challenges upended the industry’s growth: the global financial crisis in 2008, Superstorm Sandy in 2012 and the expansion of legalized gambling in nearby states. As casino revenues dropped, gaming companies began successfully challenging their property tax bills. County records show their collective property valuation plunged from a high of $13.7 billion in 2008 — when 11 casinos were open — to $3.2 billion in 2016 — when only seven properties were operating. As a result, local tax revenue plummeted and municipal debt ballooned, mostly to cover the costs of property tax refunds owed to casinos. (Today, about two-thirds of Atlantic City’s $456 million debt burden comes from bonds sold to cover those refunds.)

That debt limited the city’s ability to invest in infrastructure and services, including its fire department, which has been borrowing neighboring communities’ trucks while awaiting new equipment. The city also reduced the size of its police force, cutting dozens of officers.

With the city on the brink of insolvency, gaming companies hatched an alternative tax plan, pitching it for several years before it gained enough support in Trenton to pass in 2016. For the next decade, instead of paying traditional property taxes, casinos would make payments based on other factors, including how many hotel rooms they have and their gross gaming revenue.

The legislation, drafted in part by the Casino Association of New Jersey, set the collective amount due in 2017 at $120 million, and for each of the remaining nine years, it tied the total PILOT payment to industry performance: If the industry saw a drop in revenue, payments would also decline.

For the businesses and Atlantic City, the new system held clear advantages. Casinos would no longer challenge their property taxes in court, saving both sides time and money. And they could bank on predictability, penciling in the amounts owed for each of the next 10 years.

The 2016 legislation also included a separate tax break for gaming companies, an incentive to convince all the casinos to participate in the PILOT system. It gave casinos a discount on the investment alternative tax that they paid to finance community projects. The change would hurt Atlantic City in the short term, but lawmakers ensured that the cuts wouldn’t last forever: The tax break would expire halfway through the PILOT program, with the city seeing the full tax benefit again in 2022.

Then-Gov. Chris Christie signed the PILOT bill into law in 2016. Seeking to avert New Jersey’s first local government bankruptcy since 1938, he also placed Atlantic City under state control — a move that gave the state authority over large parts of local government, including its budget.

But the bad times didn’t last for the casinos. Two shuttered properties, the Trump Taj Mahal and the Revel Casino Hotel, changed ownership and then reopened in mid-2018 as the Hard Rock and the Ocean Casino Resort, respectively. Meanwhile, online gaming blossomed, injecting hundreds of millions of dollars into the industry. Legalized in 2013 — with the requirement that computer servers be based in Atlantic City — the sector nearly quadrupled its revenues in New Jersey in just six years, growing from $123 million to $483 million in 2019. The climb accelerated in the back half of 2018, aided by the legalization of sports betting in the state.

As a result, gross gaming revenue climbed in 2018, and then again in 2019. So did the PILOT payments, which reached $152 million in 2020, far more than the initial $120 million, which the industry had expected to be a kind of ceiling.

At the same time, the temporary break on the investment alternative tax was scheduled to expire, meaning companies would have to begin paying their full share again in 2022.

To some industry leaders, the PILOT program was starting to look like a bad bet.

They turned to a key ally.

Gaming Industry Pushes for Change

For more than a decade, Steve Sweeney lorded over New Jersey politics as the president of the state Senate. Long considered the second-most-powerful person in the state, behind the governor, the South Jersey Democrat brokered deals on everything from schools to public pensions to renewable energy.

But last year, amid a Republican wave, he met his political end in a stunning upset, falling in the November election to a little-known truck driver with no political experience. With only months left in his post, he returned to Trenton to address unfinished business. On his agenda: tax relief for the gaming industry.

Specifically, Sweeney had sponsored legislation to exempt all online gaming revenue from the PILOT formula.

The bill was a response to industry leaders, who had spent months publicly downplaying their online windfall. Hard Rock’s Lupo led the effort, making a key claim: that casinos’ technology partners were gobbling up the bulk of online wagers.

In general, a spokesperson for the Casino Association of New Jersey said, just 20% to 25% of the total online revenue in New Jersey was attributable to casinos’ own platforms. But, according to the Press of Atlantic City/ProPublica review, that number is poised to rise over the course of the PILOT program, as gaming companies increasingly make moves to reduce or eliminate third-party costs.

At a press conference in late November, Mayor Marty Small of Atlantic City backed the industry’s push to change PILOT.

“We’re guaranteed to be in no worse position than any previous year,” Small said.

At his side was his adviser, Steven P. Perskie, a former judge and onetime state lawmaker who authored the Casino Control Act legalizing gaming in Atlantic City. Perskie cited what he called a “comprehensive” financial analysis of PILOT taxes conducted by the state. “The impact of the increases that would take place in 2022 would put a significant portion of the industry in extreme financial distress,” he told reporters.

The new PILOT bill would help prevent that, Perskie said.

To be sure, the change would mean less in PILOT funds for Atlantic City. But the mayor reasoned that the loss would be offset by an increase in investment alternative taxes; the break that casinos had received on the levy would sunset as planned in 2022. But Small’s prediction would ultimately turn out to be wrong. The city’s proposed annual budget shows that this year, the two revenue streams combined are expected to total $5 million less than in the prior year.

Small did not respond to a request for comment, and Perskie declined to answer written questions from the news organizations. Neither provided evidence of the PILOT analysis they cited.

But as the legislation moved through the statehouse, other local officials, like Dennis Levinson, Atlantic County’s executive, took notice of the new financial reports being released by the Division of Gaming Enforcement, the state agency responsible for regulating casinos.

While the city’s nine casinos saw a 5% drop in in-person wagers through the first 10 months of 2021 compared with the same period in 2019, online gaming had pushed their gross revenue to $3.5 billion. In terms of gross operating profit — which regulators describe as “a widely-accepted measure of profitability” — the industry reported $592 million through the first three quarters of 2021, putting it on pace for its best year in at least a decade.

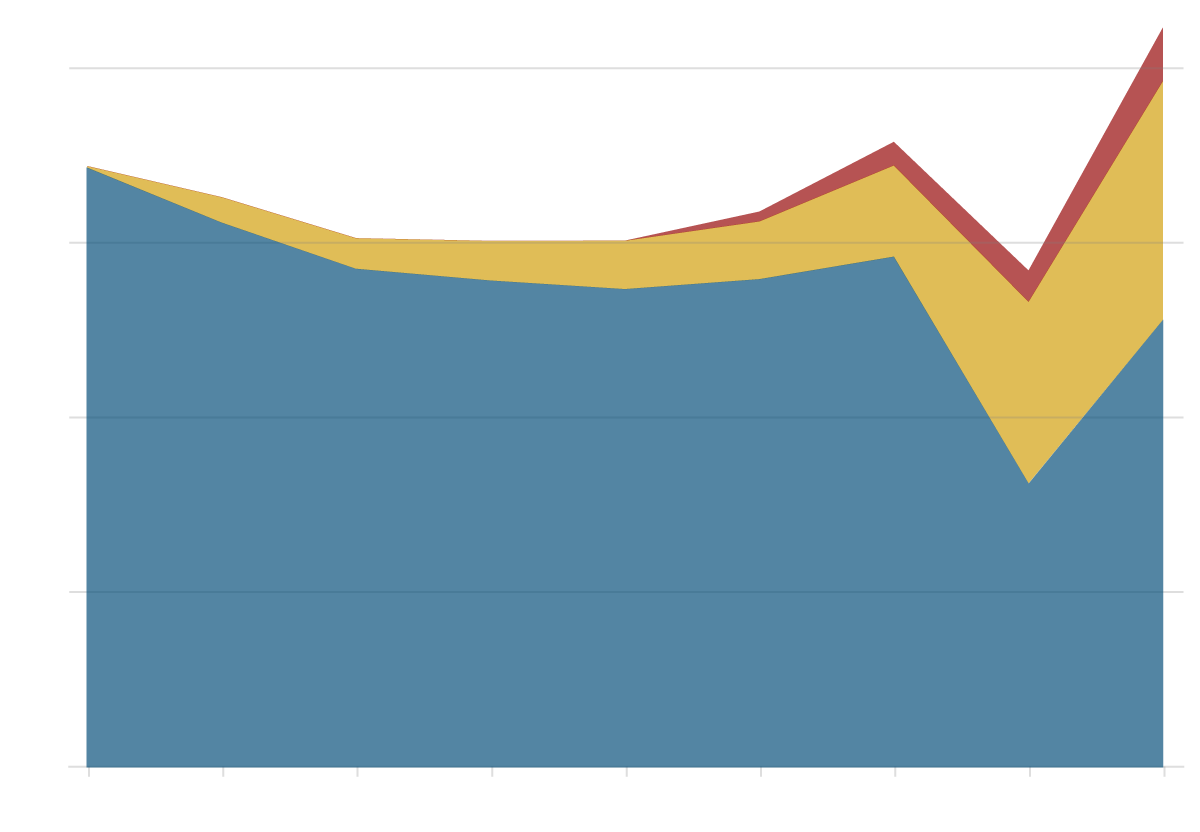

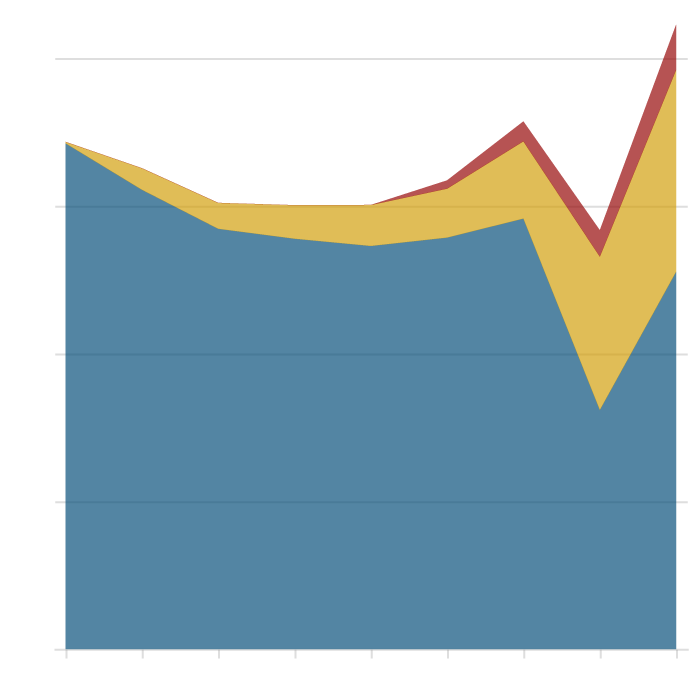

Revenue Has Jumped in the Atlantic City Casino Industry

While in-person gambling declined dramatically when COVID-19 hit, online gaming has been booming. It now accounts for a growing portion of total revenue for the casino industry.

$4B

Sports betting

Internet gaming

3B

2B

Revenue from casino wins

1B

0

2014

2015

2016

2017

2018

2019

2020

2021

2022

Sports betting

$4B

Internet gaming

3B

2B

Revenue from casino wins

1B

0

2014

2016

2018

2020

2022

Citing the gaming reports, Levinson asked Murphy to oppose the PILOT legislation.

“It is confounding that the casinos can claim they are suffering while all reports indicate they are setting revenue records,” Levinson wrote in a Dec. 2 letter. That same day, Moody’s Investors Service issued a credit opinion of Atlantic City that said, “City management is not aware of any plans to close further casinos.”

In his letter, Levinson also said changing the tax formula would violate a previous settlement agreement with the state that spelled out how much PILOT tax revenue Atlantic County would receive through 2026 — and he threatened to sue if the bill became law.

Levinson said the governor never responded. Murphy, through a spokesperson, declined to comment.

Big Action, Few Questions in the Legislature

The legislation gained momentum in early December when Sweeney made his case to the state Senate’s Budget and Appropriations Committee.

“We are risking four casinos closing,” he told his colleagues. “And that’s why this bill was proposed.”

The casino industry is the largest employer in Atlantic County, with more than 19,000 workers, and such a downturn would shutter roughly half the gaming properties. Some senators worried aloud about losing jobs; when four casinos closed in 2014, nearly 9,000 employees were laid off. None of the lawmakers, however, pressed Sweeney for evidence, and the bill sailed through the statehouse with little debate.

Indeed, the General Assembly committee spent less than four minutes on the bill to change PILOT during its Dec. 13 hearing. Nearly half that time was used by Sue Altman, state director of New Jersey Working Families Party, a progressive coalition that opposed the bill.

“We are sick and tired of watching big and successful and profitable industries like casinos pay less than their fair share in taxes,” she said.

Peter Chen, an analyst with left-leaning think tank New Jersey Policy Perspective, agreed. “The formula adopted by lawmakers in 2016 takes into account the possibility of adverse financial conditions,” he wrote in a letter to lawmakers. “It’s unclear why new changes are needed to reduce the amount casinos pay, beyond what current law provides.”

The committee members did not address the criticisms in the hearing, and just one spoke before voting. “I do have concerns about this bill,” the vice chair said, without detailing those worries. Nevertheless, he and eight other committee members approved the bill, which went before the Democrat-controlled Legislature a week later.

In the end, just four Democrats opposed the legislation, including state Assembly members Vince Mazzeo and John Armato, both of whom represented Atlantic City and a large part of Atlantic County. Armato’s defection was especially notable because he had been the sponsor of the Assembly version of the PILOT bill. In an unusual move, he had his name removed from the legislation before the final vote. “For me to move forward, I needed a lot more information, and I wasn’t getting it, which made me very uncomfortable,” he told The Press of Atlantic City and ProPublica.

“When Are We Going to Get Our Fair Share”

Today, New Jersey is reckoning with the fallout from the new law.

Levinson, the Atlantic County executive, made good on his threats to sue the state, alleging that the new PILOT formula could put several county programs at risk, including its opioid response, flu and COVID-19 vaccination initiative, and transportation services for senior citizens, disabled residents and veterans.

A judge in late February ruled in favor of Atlantic County, finding that the state violated the terms of its previous settlement agreement — a ruling that was upheld by the municipal court last month. The state, however, has not conceded, and plans to appeal.

Atlantic City has seen few improvements since the alternative property tax system began. Its budget remains flat, comparable to past years, as chronically high poverty and unemployment rates persist.

In March, Small, who supported the PILOT law despite the loss of revenue, was in Trenton, seeking more gaming money for his city. He asked lawmakers to back legislation that would send a sports wagering tax to Atlantic City instead of a state agency. The money would then be used to provide property tax relief to local residents, who have seen their tax rates rise over the past decade.

“We redid the PILOT bill, which I supported,” he told lawmakers. “But people are looking at when are we going to get our fair share of the pie.”

Indeed, the fallout from the legislation is now driving a larger debate about New Jersey’s gaming taxes, nearly all of which flow directly to the state, not Atlantic City.

Republican state Assembly member Don Guardian, a former Atlantic City mayor now in his first term representing Atlantic City and Atlantic County in the statehouse, said he plans to convene representatives from the city, county and state, as well as the gaming industry, to study the casino tax structure. Industry observers consider New Jersey the country’s most casino-friendly state after Nevada. “Let’s start taking into account that the world has changed,” Guardian said. “You need to go back and look at the whole issue.”

Meanwhile, some of the state lawmakers who initially supported the PILOT change are now questioning why it was necessary. “As more and more data started coming in on the health and vitality of the industry, it became clear to me that the idea the casinos were going to close was more talking point than truth,” said Democratic state Sen. Troy Singleton, chair of the Senate Community and Urban Affairs Committee.

During a Senate committee hearing in March, state Sen. Vince Polistina, a Republican representing Atlantic City and Atlantic County who voted against the bill in December, was more pointed with his colleagues. The new law, he said, “was done based on the premise of a charade.”

Do You Have a Tip for ProPublica? Help Us Do Journalism.

Got a story we should hear? Are you down to be a background source on a story about your community, your schools or your workplace? Get in touch.

Mollie Simon of ProPublica contributed research.