Series: No Sanctuary

The Unshackling of ICE

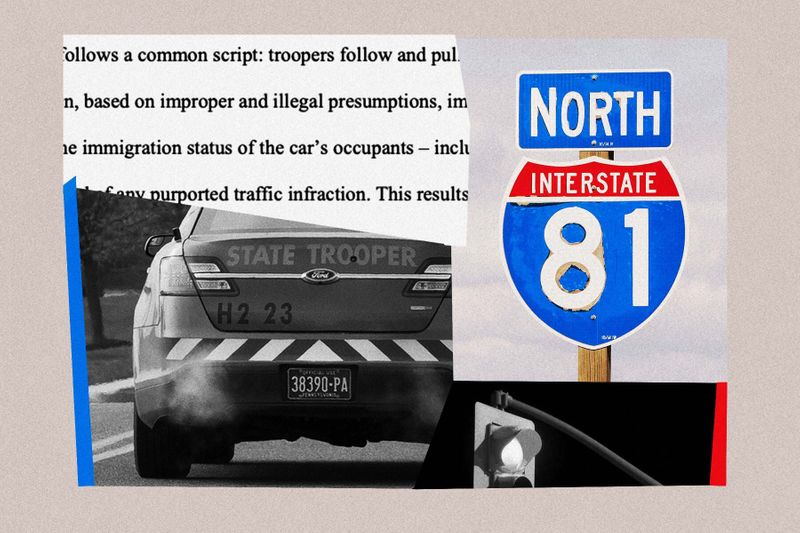

The state of Pennsylvania has agreed to pay $865,000 to settle a federal lawsuit alleging that its state troopers routinely and unconstitutionally pulled over Latino drivers, demanded their “papers” and held them and their passengers for pickup by federal immigration authorities — a practice that escalated markedly after President Donald Trump took office in 2017.

The complaint, filed by the Pennsylvania ACLU and drawing in part on a 2018 series of ProPublica articles published in collaboration with The Philadelphia Inquirer, detailed cases of state troopers stopping and then detaining immigrants under the auspices of federal immigration laws, which it alleged they had no authority to enforce. The immigrants were engaged in ordinary, legal activities, according to the complaint: traveling to see family members, driving to or from work, buying a soda in a state police barracks, awaiting medical help following a traffic accident or, in one case, returning from a job interview accompanied by a wife who was nine months pregnant.

Three of six incidents recounted in the complaint were carried out by one state police officer, Luke Macke, whose practices were revealed in the ProPublica articles.

“Our investigation found that the six incidents described in the lawsuit were the tip of the iceberg, reflecting a pattern of discrimination by state troopers against Latinos and people of color,” said Vanessa Stine, immigrant rights attorney for the Pennsylvania ACLU. “Racial profiling and discrimination have no place in law enforcement.”

The complaint alleged that the police actions violated the plaintiffs’ constitutional protections against racial and ethnic discrimination and illegal searches and seizures.

The settlement in Marquez, et al. v. Commonwealth, et al., signed on Wednesday, includes state payments to 10 plaintiffs, attorneys fees and extensive changes in state police policies. The new rules bar officers from stopping drivers based on their suspected nationality or immigration status, and from asking drivers about their immigration status unless it relates to a criminal investigation. They also state clearly that the state police department “does not have jurisdiction with respect to civil immigration enforcement.”

At the time of the ProPublica series, the state policy was significantly different. The Trump administration was ramping up immigration enforcement, and many states and municipalities were enacting explicit limits on how officers questioned immigrants or communicated with U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement. Others formed partnerships with ICE that deputized local police to enforce immigration laws.

Pennsylvania did neither, providing no guidance to troopers on how to handle encounters with undocumented immigrants, a state police spokesperson told ProPublica in 2018. Individual troopers decided on their own whether to question drivers and passengers about immigration status, summon ICE, or hold immigrants without a warrant until ICE arrived, according to ProPublica’s investigation.

In the year after Trump took office, these practices helped the regional ICE field office covering Pennsylvania, Delaware and West Virginia tally more “at-large” arrests of undocumented immigrants without criminal convictions than any of the 23 other field offices in the country. These were immigrants picked up in communities, not at local jails and prisons. The state police did not track these encounters, so there was no system for monitoring their impact.

“The whole central Pennsylvania area is like the opposite of a sanctuary city,” Anser Ahmad, an immigration lawyer, told ProPublica at the time. “Cops are out there looking for people.”

The agency’s new policy requires the department to keep records of all traffic stops, arrests and detentions of foreign nationals and to make them available to plaintiffs’ attorneys for a year.

“I am confident these changes to policy and training will ensure the department is in compliance with current case law,” said state police commissioner Robert Evanchick.

According to the ACLU, none of the officers named in the complaint were disciplined, and all remain on the force. A state police spokesperson said the department does not discuss disciplinary matters. Macke, who did not respond to requests for comment in 2018, has not responded to a request for comment for this story.

Almost all of the plaintiffs in the lawsuit ended up in deportation proceedings after state troopers turned them over to ICE. According to the complaint, all “suffered substantial damages including emotional trauma and distress, loss of enjoyment of life, and financial damages, some or all of which may be permanent.” The ACLU said all remain in the U.S.

One of the incidents in the lawsuit involved Rebecca Castro, the only U.S. citizen among the plaintiffs. She was driving her boyfriend (now husband) Carlos Amaya Castellanos and a co-worker to a construction job in Maryland when Macke pulled them over in May 2018. Castro provided her driver’s license, registration and insurance, which should have ended a legal encounter. But Macke contended that her truck and trailer looked suspicious. She asked what could be suspicious about an open-air trailer. Rather than respond, she said, he turned to investigating the immigration status of her passengers — evidence, according to the complaint, that the traffic stop was “impermissibly based on Ms. Castro’s and Mr. Amaya Castellanos’ perceived race, color, ethnicity, or national origin.”

According to the complaint, Macke held the three of them without a warrant for 90 minutes, demanding their identification and forcing all, including Castro, to submit to telephone interrogations with an ICE officer. Two ICE officers arrived soon after, arrested Amaya Castellanos and his co-worker and placed them in deportation proceedings. Macke had Castro’s vehicle towed, leaving her at the roadside without transportation.

“We were going to work. We weren’t doing anything else. Because of the simple fact that he saw we were Hispanic, he thought this was his lucky day and he was going to take all three of us,” Castro said, fighting back tears, in a video posted to Instagram. “But it turned out I was a citizen. He couldn’t take me. So that’s why I decided to fight the case — so that it didn’t happen to other people — because honestly the officers don’t get the damage they’re causing.”

Update, April 8, 2022: This story has been updated to include a Pennsylvania police spokesperson's comment that the department does not discuss disciplinary matters.