For more than 30 years, the Johnson & Johnson unit that makes Tylenol has delivered a consistent message: it’s the pain reliever that doctors recommend most.

McNeil Consumer Healthcare marketing experts have spent hundreds of millions of dollars promoting it through television and magazine advertisements. It is a refrain that many American consumers know by heart.

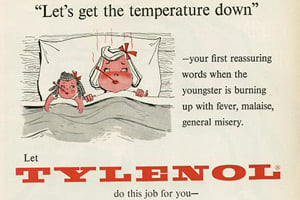

A History of Advertising

Marketing prowess helped turn Tylenol into one of America’s most popular pain relievers. See ads and commercials from some of the company’s campaigns.

But it’s also not the whole story, according to internal company records that have emerged in a trial pitting McNeil against a New Jersey woman who claims that Tylenol sent her to the hospital. The trial is set to go to the jury today.

The regular surveys conducted by McNeil show that while most doctors recommended the drug, they also told patients to take the medication at doses far less than the daily maximum allowed by the federal government, according to the previously undisclosed documents.

The reason? Doctors worried that what the government and company described as the maximum safe dose of the active ingredient in Tylenol, a compound called acetaminophen, was too close to the level that can damage the liver and even lead to death.

In 2002, for instance, McNeil noted the “pervasive problem” of health care professionals, or HCPs, recommending doses lower than maximum daily dose of 4 grams of acetaminophen per day, or about 8 extra-strength pills.

“Less than half of HCPs recommend the maximum daily dose,” one internal company memo said. The memo – labeled “Restricted Document. Distribute and Disclose on a Need to Know Basis” – also said patients had stopped taking the drug or reduced their intake, many due to safety concerns. The “lost dollars” or “financial impact” on Extra Strength Tylenol, the memo estimated, would be $3 million from the drug’s $430 million in projected annual revenue.

The latest revelations come in a trial over the issue of whether McNeil should have done more to mitigate the risks of Tylenol. There are about 200 other similar cases pending against McNeil, most in federal court in Philadelphia. The company is contesting all the suits, arguing that its product is safe when taken as directed.

The parties in the New Jersey case were set to present their closing arguments today but the jury has already seen previously confidential documents offering a rare view into how corporate managers weighed the safety risks and the financial rewards of one of America’s most iconic brands.

The documents show that for decades McNeil knew that doses near the recommended level could cause liver injury, that some patients used too much of the drug, and that many doctors were telling patients to take less than the recommended dose.

Meanwhile, the company marketed Tylenol as the most recommended pain reliever and calculated how increasing the amount of the drug that arthritis patients take each day could boost the company’s revenues by $25 million, according to one McNeil document.

Last week, New Jersey Superior Court Judge Nelson C. Johnson denied a motion by McNeil to grant a verdict in its favor. But the jury will face a higher hurdle to hold the company liable. It must find that the drug was not only defective but that the defect caused injury to the plaintiff, Regina Jackson.

Last week, the judge, out of ear shot of the jury, noted that Jackson’s “conduct violated just about every recommendation and warning.” But Johnson, ruling before McNeil presented its defense, also said he had a “problem” because of some of the evidence he had seen during the trial, especially involving drug misuse.

“This product is marketed very heavily. It’s marketed as the number one pain reliever, number one recommended, and I don’t doubt that it’s safe if it’s used properly,” Johnson said, explaining why the trial should continue. “But there also seems to be a fair amount of evidence that it’s predictable that some people won’t use it safely. And again, I don’t think we exist to protect people from themselves, but I do think when it’s foreseeable, I need to know that the manufacturer’s done everything they can to deal with that situation. And I’m not satisfied that they did.”

A McNeil spokeswoman, Jodie Wertheim, declined to comment, but in a statement last month she emphasized the safety record of the company and the drug.

“Johnson & Johnson Consumer Inc., McNeil Consumer Healthcare Division is committed to providing consumers with safe and effective over-the-counter medicines and recommends consumers always read and follow the product label,” she said. “The company has acted appropriately, responsibly and in the best interests of patients regarding Tylenol, which has one of the most favorable safety profiles among OTC pain relievers.”

Jackson, a New Jersey state employee, claims she inadvertently exceeded the recommended daily dose for Extra Strength Tylenol for a couple of days in 2011 and wound up hospitalized with elevated liver enzymes. At the time, the daily limit was no more than 4 grams, or 8 pills of 500 milligrams each.

Under New Jersey law, a manufacturer can be held liable even if their product was misused “if the misuse was objectively foreseeable,” the judge said last week.

A 2013 investigation by ProPublica and This American Life examined McNeil’s efforts to protect its best-selling brand, including opposition to warning labels, dosing restrictions and even some public awareness campaigns. But the Jackson case has shed new light on what company officials knew about their product, including plans to lobby the Food and Drug Administration to block new recommended safety restrictions.

As far back as 1973, McNeil documents show, company officials were told that the more powerful Extra Strength Tylenol should be handled by doctors and not recommended to the general public since “the vast majority of patients, probably 98% are effectively treated” with Regular Strength Tylenol, which contains 325 milligrams in each dose.

In light of a scientific report showing hepatic, or liver, damage at 6 grams per day, a company executive recommended McNeil look at “modifying the acetaminophen molecule to avoid hepatic damage.” McNeil did subsequently research making a safer version of acetaminophen, but that effort failed.

Decades later, after Extra Strength Tylenol became the best-selling version of the brand and reports emerged of patients suffering liver injury near the recommended dose level, health care professionals repeatedly voiced concerns to McNeil about the drug’s risks.

A 1995 survey found “a significant increase in the percentage of physicians citing safety issues as disadvantages” of acetaminophen, often involving liver toxicity.

Moreover, the same survey found that doctors were twice as likely – 66 percent to 33 percent – to recommend a daily dose of 2.6 grams per day – 8 regular strength Tylenol pills – versus 4 grams, 8 doses of Extra Strength Tylenol.

The plaintiff also introduced records from a 2004 national sales meeting in which executives were told that “physicians state 4 g/day is ‘close’ to an unsafe dose. Currently recommend 2.5/day on avg.”

The document’s “conclusion”: “MUST reassure TYLENOL is safe AND effective at 4 g/day.”

In 2011, McNeil dropped the maximum recommended daily dose of Tylenol to 3 grams after an FDA panel recommended doing so.