Series: Cold Justice

The Outrage and Promise of Untested DNA From Rape Victims

Julienne Wood was walking through the aisles of Costco this June when a college friend rang her up.

“Jules, where are you?” asked her friend, out of breath and barely able to speak. “I have something REALLY BIG to tell you. … You’re gonna finally get answers you’ve been looking for. … I sent you a series of articles from ProPublica. … It’s big — way, way bigger than we thought.”

Wood rushed home, opened her computer and began reading. She started out with our last dispatch about how the 1983 rape and murder of Goucher College student Alicia Carter had been solved after a man named Alphonso Hill confessed to the crime this year.

“It was the most surreal experience of my life,” Wood later recalled.

She finally had a name, a picture and a good idea of who raped her 41 years ago.

“It’s a lot to digest,” she wrote in one of her emails after reading through the series. “But always I’ve felt in my heart that Alicia Carter was murdered by the same person.”

Carter was a classmate of hers at Goucher. Police found Carter, who was just entering her senior year, stabbed to death in August 1983. She was discovered in the same wooded area where Wood was raped in 1980 and where Martha Southworth, another student, was raped in 1979, at the outer edge of campus. By the time authorities found Carter’s body, much of the forensic evidence had deteriorated, according to police records.

Southworth, a Goucher senior, was walking back into campus at night in 1979 when Hill attacked her. The case went unsolved until nearly three decades later, when evidence from her rape examination was tested and linked to Hill’s DNA. Hers was one of nine cases in Baltimore County that led to convictions after police tested microscope slides from sexual assault examinations that a doctor had saved. Hill was also convicted of a 1983 rape in the city of Baltimore using fingerprint evidence, and he was connected using DNA to other rapes in which the women chose not to prosecute.

After reading about Carter’s case, Wood called the police immediately.

Her question: Could her attacker be the same man?

The answers she has since received have been “life-changing,” Wood said. “It’s the most freeing experience in the world.”

After Hill confessed to raping and murdering Carter this May, he also confessed to committing possibly a dozen other sexual assaults for which he has not been charged, according to the audio recording obtained by ProPublica. Detectives presented him with a list of the unsolved cases that mirrored his modus operandi. Wood’s 1980 case was on the list.

“I read through and there look like some incidents that could be mine,” he told detectives, with the caveat that he couldn’t get into specifics because he couldn’t remember. “I am saying some definitely look like me,” he said of several cases, including Wood’s. Wood said a sergeant with the Special Victims Unit reached out to her and told her that she will receive official documentation in the coming weeks that indicates her case is closed due to Hill’s admission.

Hill has been convicted of other rapes and is in prison until at least 2047, when he would be 95 and up for parole for the first time. He will likely die behind bars, according to Baltimore County State’s Attorney Scott Shellenberger, who offered him testimonial immunity for crimes he confessed to during the May interview so that families and survivors could get some closure.

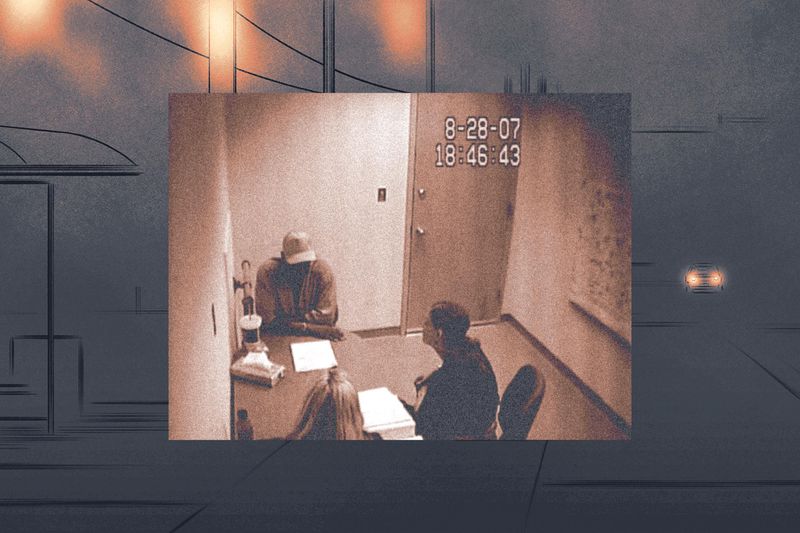

I had requested Alicia Carter’s case file and the files for several unsolved sexual assault cases from police through Maryland’s open records act after reviewing old case files and newspaper articles. My questioning prompted the police investigation and interrogation of Hill.

Detectives told Hill that they had DNA in some of the cases and that confessions could allow him to avoid trials and more public exposure.

Wood has reconnected with Southworth, the Goucher alumna raped by Hill in the same area one year before she was. The two have spent hours communicating on the phone and over email, and they’ve connected with other Hill survivors including Laura Neuman, whose 1983 case put Hill in jail two decades after the fact when police processed a fingerprint from her case that had previously been ignored. Neuman made the unusual decision to go public. “I understand it’s a very personal experience, but we will never change this if we don’t start talking about it,” she explained. She told me she always believed Hill had attacked others. A television interview she gave proved to be a crucial clue in helping solve a slew of other Baltimore County cases.

Neuman, Southworth and Wood have since started a private Slack group where they can communicate and organize. They want to help other survivors get validation and support, raise funds to test the remaining DNA in the archive created by Dr. Rudiger Breitenecker at Greater Baltimore Medical Center, and possibly get their cases solved.

So far, about 200 of the more than 2,200 cases saved by the doctor have been sent for testing or have been fully processed for DNA.

They are calling their group OURstories: Taking Our Power Back.

This is some of their story.

It starts in 1979, when Southworth was in her senior year at Goucher College; in 1980, Wood enrolled as a student there as well. By then, the school had been women-only for nearly a century (it’s now co-ed), and its list of graduates read like a timeline of female progress — suffragists, federal judges, astronomers, a vice commandant of the U.S. Coast Guard.

Southworth remembers that at the time the school motto was “Brave New Woman.” The message, she said, was “that you could do and be anything you want.”

You are both from out of state. What drew you to Goucher?

Wood: I liked the vibe, the intellectual energy, the admissions counselor who challenged me during my interview, the beauty of the campus, the self-confidence of the students.

Southworth: My parents had connections to the area and my sister had gone to an all-women’s college and had a good experience.

You two were assaulted one year apart. Julienne was a new freshman and Martha was a senior. How did you cope with it?

Wood: I went home initially for a few days, but returned right away. Goucher healed me, helped me survive, and the Goucher friendships I developed were a lifeline. But even with these friends, I couldn’t talk about what happened, so I can’t say I coped with it. I kept it a secret for decades. Ironically, I recently had started therapy with a very relaxed, funny but skillful psychologist who somehow cracked 40 years of silence when I let it slip out that I’d been attacked years ago, in college. At the time, I don’t think he quite understood the magnitude of my secret, but he knew I needed to dig deeper into my emotional scars, and he started me on this journey.

Southworth: I struggled with hypervigilance for a long time but was determined that this monster was not going to take anything else from me. The assault stiffened my resolve not to allow him to have any more power over me. I had a 3.25 GPA until that year. I dove into my studies and pulled it up to a 3.75. I had a small circle of friends with whom I chose to share what happened. They gave me a lot of strength, along with my family. My mom would tell me that I am a survivor, not a victim, and my dad put me in touch with a young psychologist colleague of his who had been raped. She had just had a baby and she showed me that it is possible to move forward and lead a normal life.

What was your reaction to the news of Alicia Carter’s murder?

Wood: I blocked it out. I had to. I understood the implications, and they were devastating. She was found stabbed to death in the exact same woods where both Martha and I had been dragged into, at gunpoint, at knifepoint, walking back to campus alone at night. It was now the beginning of my senior year, and I needed to finish school. I pretended Alicia’s murder didn’t happen. I wasn’t emotionally capable.

Southworth: It was unnerving. Her body was found near the same spot as where I was attacked. I had graduated and left Baltimore by then, but chose to go back. I felt I needed to go back and prove that I did not have to be afraid anymore. That fall, the director of residential life at Goucher put me in touch with Julienne. We compared stories and knew without doubt that we had been attacked by the same person.

Martha, what was your reaction when a detective called you in 2007 to tell you that they might be able to solve your case after nearly three decades because a doctor had saved the evidence from your rape exam?

Southworth: I was so grateful. Both Laura and the doctor are my heroes. To have a name and a face that allowed me to have a direction for my outrage was life-changing. I finally felt like I could bring [the rape] out of the closet. It also freed me up to try to help other young women. Sadly, I know of many women, daughters of friends or friends of my daughter, who are struggling with the aftermath of rape. I try to offer myself up as a model and a beacon of hope, like the psychologist who was also a family friend had helped me.

What was your reaction to the recent news about Carter’s case being solved this May?

Wood: Shock. Disbelief. Anger. Rage. Horror. Relief. Incredible relief and compassion for Alicia’s family, for her close friends from Goucher who had been working so hard all these years to keep her memory alive, through a scholarship fund in her name, through a garden dedicated to her.

Southworth: It was very emotional for me. I felt an overwhelming sense of sadness for Alicia and her family, and it reawakened a deep feeling of fright that this could have happened to me, Julienne, Laura and others I have yet to meet. His lack of humanity is bone-chilling.

The DNA from Martha’s rape examination became important evidence to show Hill’s pattern in and around Goucher. It was a key part of the puzzle shedding more light on Carter’s and Wood’s cases. How does that make you feel?

Southworth: This was very validating that I had made the right decision. It took courage and I had three administrators from Goucher by my side that night to help me through it. They put me in touch with an advocate at a rape crisis center who told me that even if the evidence that was collected could not help me, it might provide information that would help solve someone else's case. That was enough for me to go ahead.

Julienne, what would you tell law enforcement and survivors about what it is like to get some form of closure after 40 years?

Wood: It’s the most freeing experience in the world. I’m taking my power back, taking back things Alphonso Hill took away from me 41 years ago. I guess I feel inspired. I feel a new purpose. Maybe my next purpose in life will unfold dramatically differently than anything I ever imagined. And that leads to hope.

Why are you speaking out and what do you hope to do with your OURstories group?

Wood: What happened to me, and Martha, and to Alicia, wasn’t about Goucher College. It wasn’t about Towson [the suburb where Goucher is located] or Baltimore either. It was way bigger. This was about a time in history when serial rapists and murderers could roam more freely. It was happening all over the country. There was no DNA technology to stop them. But that’s not true anymore. Yet there still are survivors without answers. I hope that our stories might attract more Alphonso Hill survivors to our forum as a place to find purpose and shared meaning. Because collectively, our voices are stronger than individually, and we have many allies. I hope we can get the rest of the DNA tested and help other women get their cases closed.

Southworth: I hope that what comes from this is an ability to lend some strength to other women who are struggling in the aftermath of rape and to help promote healing. Laura and my dad’s colleague did that for me. I want to be that catalyst for others. I think it’s time to bring this out of the shadows.

To contact the reporter, message her at @cdrentz on Twitter. For survivors of sexual violence in Baltimore County and the city of Baltimore, TurnAround provides counseling and support.