Dispatches from Freedom Summer

Long a Force for Progress, a Freedom Summer Legend Looks Back

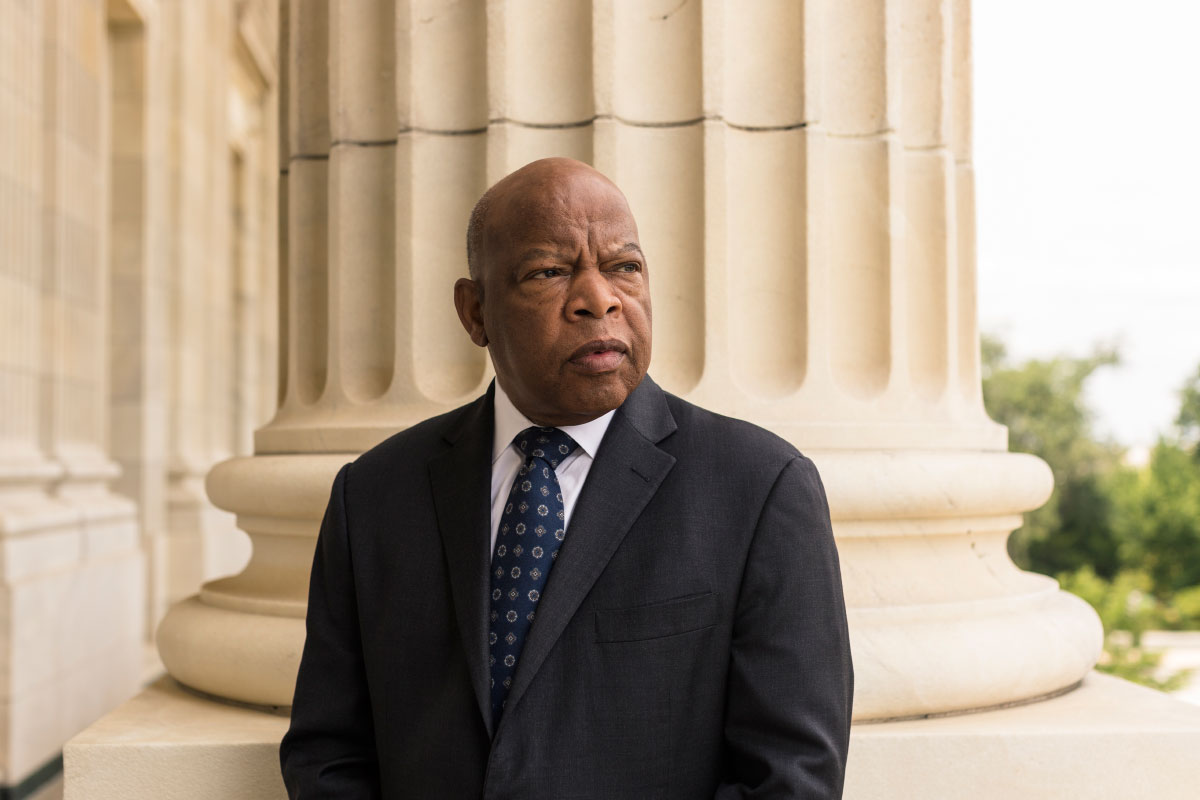

Georgia Congressman John Lewis talks about what changed — and didn’t — because of the movement he helped to lead 50 years ago.

Rep. John Lewis, D-Ga., is the most iconic living veteran of the Civil Rights Movement, the sole survivor of the leaders known as the Big Six. He is the only speaker left from the pivotal 1963 March on Washington.

Lewis was a Freedom Rider and was among the first to launch the sit-ins, protests to integrate lunch counters and other spaces. In 1964, he traveled the country, recruiting college students to travel to the deepest South for Freedom Summer. A year later, the blood Lewis spilled in the now-infamous clash between peaceful marchers and state and local police on Selma’s Edmund Pettus Bridge helped propel the 1965 Voting Rights Act through Congress.

About three weeks ago, I sat down with the congressman to talk about his role in Freedom Summer and the battles still to come as part of our series commemorating the effort’s 50th anniversary. This week marks the culmination of Freedom Summer, when black Mississippians challenged Mississippi’s all-white delegation at the Democratic National Convention in Atlantic City.

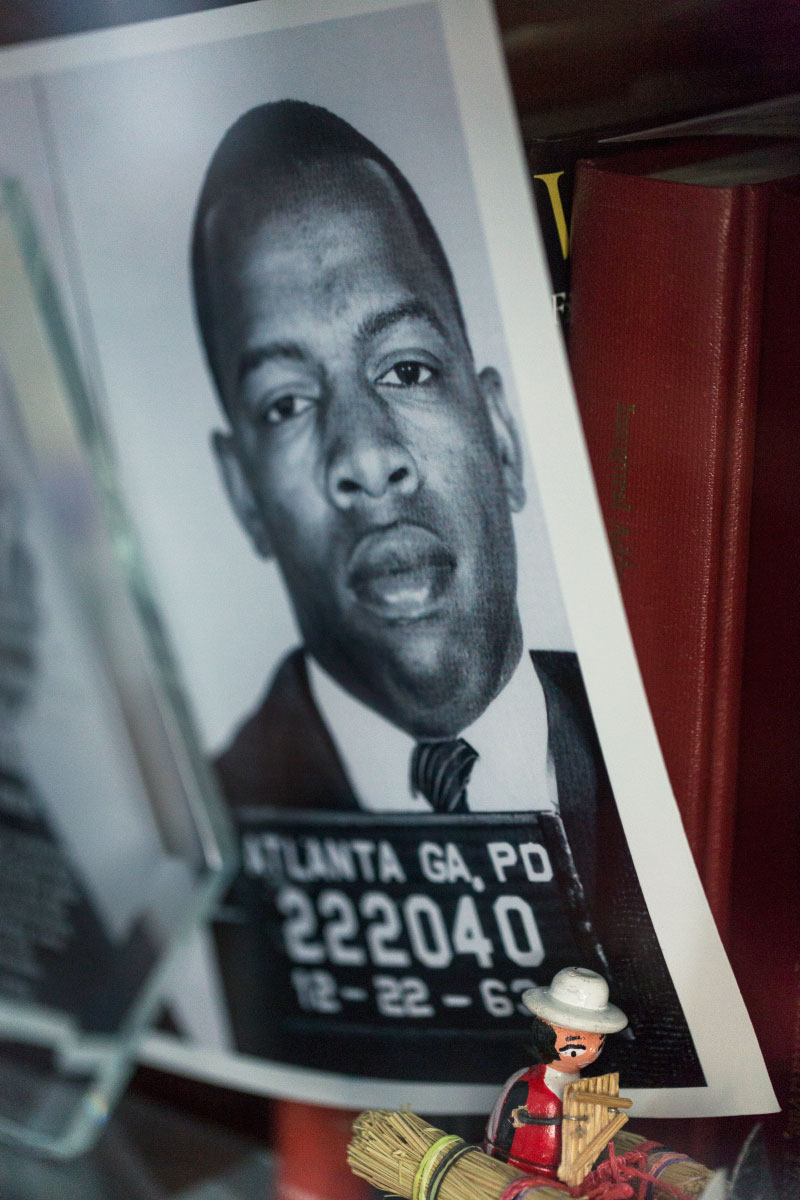

Today, Lewis represents Georgia in the House of Representatives, in a seat that wouldn’t have existed without Freedom Summer and the larger civil rights movement. Black and white photos of the struggle and its leaders adorn the walls of his office, turning them into a historical mosaic.

At the time we met, we could not have known that eerily similar images would soon be emerging from a small Missouri town after a white police officer killed an unarmed black teen, prompting protests and a virulent response from law enforcement that included tear gas, tanks and rubber bullets.

Last night, Lewis marched with demonstrators in Atlanta who were supporting protestors in Ferguson, Mo. We were unable to speak with Lewis about the situation in Ferguson, but parts of this Q&A seem prescient in how they reveal the ways in which, despite great progress, race remains an open wound in this country.

Q: You had left college to start working on civil rights. In 1964, you traveled across the country to convince other students to do the same thing. The students who ended up coming were largely white; they were leading more privileged, safe lives. How did you convince these students to give up the relative safety of where they were to come to what was one of the most dangerous places?

A: During the summer of 1964, SNCC, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, along with the NAACP in Mississippi and CORE launched Mississippi Freedom Summer, to urge African Americans to become participants in the Democratic process, to register to vote. As you well know, in 1964, the state of Mississippi had a black voting age population of more than 450,000 and only about 16,000 blacks were registered to vote. Many people of color lived in fear. People had been arrested, jailed, beaten. Emmett Till had been lynched. People had been murdered. Medgar Evers had been assassinated in 1963. Mississippi was a dangerous place. I grew up in rural Alabama and Alabama was bad but we all saw Mississippi was worse.

I visited Mississippi for the first time in May of 1961, going on the Freedom Rides. (I was) arrested, jailed, in a city jail, the county jail, and later taken to the state penitentiary at Parchment. I knew or had some idea of what we were getting involved with. It was dangerous, very dangerous, but we had to go there. And we convinced students, young people, religious leaders and others to support an effort and people responded.

Q: What did you say, though, when you were going to visit these campuses, to convince people to leave that behind to come join the fight?

A: Well, the issue of civil rights, it was the issue to deal with. We had had the March on Washington in 1963. These young people, these students, had witnessed the march and some had participated in the march. Many of these young people knew what happened in Birmingham during the spring of 1963. Bull Connor used dogs and fire hoses on children and women. So, it was not hard to convince young people, to convince students and religious leaders to come to Mississippi.

They responded. We kept saying the vote is precious, the vote is important. I had said earlier, on Aug. 28, 1963, when I spoke at the March on Washington, I made the statement after seeing an article in The New York Times concerning women in southern Africa attempting to register to vote and participate in the political process, and I said something like, “One man, one vote is the African cry. It is ours too; it must be ours.”

And that became the rallying cry for the young people in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. All across America, on college campuses where we had friends of SNCC, people were wearing the buttons saying “One Man, One Vote.” It was on our letterhead, it was on posters, so people knew something about this idea of getting people to register to vote and they wanted to be part of it.

We knew by appealing to students and saying we need at least 1,000 students to come. And you’re right the great majority of the young people were white and they came from the North. But some white Southerners participated and many black students came from southern schools and from southern communities and from places like Howard (University) and Fisk University and Tennessee State University. As a matter of fact, two Japanese students… came from Canada and worked on the summer and later became SNCC volunteers in the South. So it was black and white, Latinos and Asians that participated in the Mississippi Freedom Summer.

Q: You yourself were a child of sharecroppers who sacrificed so that you could go to college. How were you able to make the decision that you were willing to leave college for a period of time to fight for civil rights?

A: Well, it was important. It was important. Growing up in rural Alabama, 50 miles from Montgomery, I saw the signs and symbols of segregation and racial discrimination – I didn’t like it. I had been deeply inspired by the action of Rosa Parks, the word and leadership of Martin Luther King Jr. I had heard about Emmett Till, when I was 15 years old in 1955, and I kept thinking that this could be one of my first cousins traveling from Buffalo, N.Y., to rural Alabama during the summer of 1955. So it was Emmett Till, Rosa Parks, Martin Luther King Jr., the Little Rock Nine, all sort of inspired me to find a way to do something. And when I had an opportunity, had a chance, and became the chair of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, I made a commitment to do everything possible to end discrimination and end segregation.

Q: A lot of people saw things they didn’t like, and weren’t able to or didn’t actually do anything. What was the difference for you?

A: I became as someone growing up very, very poor in rural Alabama and seeing how people were being treated simply because of the color of their skin, and I saw the signs, I saw the photographs. That said to me, “You have to do something.”

I heard Martin Luther King Jr. speaking on the old radio and it seemed like Dr. King was speaking directly to me, saying, “John Robert Lewis, you too can do something. You can make a contribution.”

I met Rosa Parks, at a young age, I met Dr. King at a young age. It changed my life. And set me on a path.

Q: Where did you meet them?

A: I met Rosa Parks in Nashville, Tenn., as a student there in ‘57 at the age of 17. The next year in 1958, I met Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in Montgomery in the First Baptist Church, pastored by his colleague, the Rev. Ralph Abernathy.

I had sought his counsel, his help. I wrote him a letter before going off to college. I wanted to attend a little school called Troy State College, it’s now called Troy University, only 10 miles from my home. I submitted my application, my high school transcripts. I never heard a word from the college. So I wrote a letter to Dr. King. I did not tell my mother and my father, any of my sisters or my brothers, or any of my teachers.

Dr. King wrote me back, sent me a round-trip Greyhound bus ticket and invited me to come to Montgomery to meet with him. And I remember that Saturday morning, in March of 1958, a young lawyer, a young African-American lawyer – (I’d) never met a lawyer before, black or white – a man by the name of Fred Gray.

Q: I’ve met Mr. Gray.

A: He was a wonderful man. (He) met me at the Greyhound bus station in downtown Montgomery, and drove me to the First Baptist Church… and ushered me into the pastor’s study, and I saw Dr. King and Ralph Abernathy standing behind a desk. And Dr. King said, “Are you the boy from Troy? Are you John Lewis?”

And I said, “Dr. King, I am John Robert Lewis.” I gave him my whole name, and that was the beginning. I often think if it hadn’t been for Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., I don’t know what would have happened to me.

After the discussion with him telling me what could happen if I decided to insist on going to Troy State, that my family home could be bombed or burned, they could lose the farm that they had bought by then and I went back and had a discussion with my folks, telling them that Dr. King said we may have to file a suit against the state of Alabama, against Troy State College, and what could happen. And they were so afraid they didn’t want to have anything to do with it. So I continued to study in Nashville. It was in Nashville that I met a gentleman by the name of Jim Lawson, James Lawson, who became our teacher. He taught us the way of peace, the way of love, the way of nonviolence. So a small group of students from Vanderbilt University, Peabody College, Fisk University, Tennessee State, Meharry Medical School, and American Baptist College met every Tuesday night at 6:30 p.m.

And we studied what Gandhi attempted to do in South Africa, what he accomplished in India. We studied Thoreau and civil disobedience. We studied the great religions of the world. We studied what Dr. King was all about in Montgomery. And in the fall and winter of 1959, we had what we called test sit-ins at the lunch counters and restaurants. And then by February after the sit-ins started in Greensboro, N.C., Feb. 1, 1960, we started sitting in on a regular basis.

And I was one of the early participants, one of the first participants as a matter of fact. We would be sitting there in an orderly, peaceful, nonviolent fashion waiting to be served, some black and white college students, and someone would come up and spit on us, or put a lighted cigarette out on our hair or down our backs, pour hot water or hot coffee on us, and we would look straight ahead and continue to sit. And that went on for a whole month and then on Feb. 27 I got arrested with 89 students. That was my first arrest.

I felt free. I felt liberated. And I couldn’t turn back. So as my parents, grandparents and great grandparents had said, “Don’t get in trouble, don’t get in the way.” I got in trouble, I got in what I call good trouble and necessary trouble and I’ve been getting in trouble ever since.

Mississippi Summer just didn’t happen. It was this build up. See, during early summer and late summer of 1961, almost 400 of us had gone to jail. We filled the city jail in Jackson, the county jail in Jackson, and then the state penitentiary in Parchmont. So many of these young people and religious leaders who had left Mississippi went to other parts of the country, so three years later when we started talking about Mississippi Freedom Summer, there was a reservoir of goodwill towards being involved, helping to change that state, and in doing so, we were helping to change the South.

Q: I was reading some of the old SNCC material and correspondence leading up to Freedom Summer, and one of the things they’d said was all of the efforts there had failed to crack Mississippi. There was this feeling that all these things that had been tried in other places were not succeeding in Mississippi and you even said if we crack Mississippi we’ll likely be able to crack the system in the rest of the country. Why was Mississippi so difficult?

A: In the state of Mississippi, I think there was state-sanctioned violence against nonviolent participants in the movement. You had something there called the State Sovereignty Commission. They kept files, they kept records. People would show up at meetings, they would take down their license plates, check on them. So there was fear, a tremendous amount of fear. And we felt as (Freedom Summer organizer) Bob Moses said from time to time, we have to bring the nation to Mississippi. We have to make what Dr. King’s father, Daddy King, would say, “We have to make it plain.” We have to put the light.

Mississippi was a closed society and we had to open it up. We had to put a spotlight on it. And that’s what we did.

Q: You said if it hadn’t been for Freedom Summer, there would be no Barack Obama. Talk to me about that.

A: I believe that. Mississippi Freedom Summer not only had changed the South and Mississippi, but it helped change the nation. The Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, that came out of Freedom Summer, the testimony of Fannie Lou Hamer, testifying before the Democratic credentials committee at the convention in Atlantic City in 1964 helped educate and sensitize America. And because of what happened in Freedom Summer, the education, the organizing effort, and sadly the murder of the three civil rights workers, it was painful. And I say to people today, these three young men were not murdered in the Middle East or Eastern Europe, Africa or Asia, or Central or South America, but they were murdered right here in America. And in a real sense, they must be looked up on as the founding fathers of a new America.

What happened to them pricked the conscience of America, but the African-American community in the state of Mississippi probably became more politically aware, more politically assertive and more politically organized than any other group. When we went to Atlantic City it was an organized effort, people knew why they were standing up and fighting and taking that long trip, from the heart of the Delta in Mississippi, from Jackson, or other parts of the state to Atlantic City and because of that, three brave and courageous women, black women, Fannie Lou Hamer, Annie Devine, Victoria Gray, challenged the seating of the Mississippi congressional delegation. And all of that helped to educate, not just people in Mississippi and other parts of the South, but people in the nation.

Selma came a year later, but Mississippi helped lay the foundation for Selma. So, if it hadn’t have been for Mississippi, and Selma and Mississippi Freedom Summer, put it all together, I don’t think Bill Clinton would have been elected, I don’t think Jimmy Carter would have been elected. Barack Obama wouldn’t be president of the United States.

Q: We know that the majority of white voters did not vote for Barack Obama. He was elected by a coalition of voters of color and white voters and that in this last election, black voter participation was actually the highest of any group. It seems like there is a direct line there, that you couldn’t see those levels of black voting participation if you hadn’t had all of these things that we just talked about.

A: It all is part of a continuum. People have been told, black people and young people wouldn’t get out and vote in the last election. They kept saying they are not going to vote, they are not going to vote. And they did turn out and they did vote.

Because people understood so well that people suffered. I remember being in Ohio, the Sunday before the election… and then going to an early voting site where people were standing in line and I kept saying, “Don’t forget the three civil rights workers. Don’t forget the bridge in Selma.”

And the young people, black and white, got it. One thing about the African-American community – I don’t need to tell you this – but if you go to a state like Mississippi and then you go to a city like Chicago, so many of the families can be traced back to Mississippi. If you go to Detroit, many of the families can be traced back to Alabama. So people understand that. They get it. And a tremendous amount of the support that we received during Mississippi summer came from the African American churches based in Chicago, based in Alabama and other parts of the South. And many of the young people that had been in Mississippi during the summer of 1964 came to Selma during the spring and summer of 1965. They related to what was happening.

A lot of people convinced their parents and their grandparents to cast their lot with Obama. I kept hearing people saying to me, “My son, my daughter, my grandchildren said ‘You’ve got to vote for Barack Obama.’”

Q: You got very fiery after the Supreme Court ruled on the Voting Rights Act last year. You, of anyone, understand the cost paid to get the Voting Rights Act passed and why it was so important. How did it feel the Supreme Court used the success of the act to rule against it?

A: It was unreal. It is unbelievable. When I heard about the decision, I had a sense of righteous indignation. I wanted to cry, but the tears just didn’t come.

I have said on many occasions that the vote is precious. It’s almost sacred. It is the most powerful nonviolent tool or instrument that we have in a democratic society. And every citizen must be able to use that vote, and when they register and then vote, their vote must be counted.

People gave a little blood and some people gave their very lives. I gave a little blood on the bridge in Selma and I almost died for the right of all of our citizens to become participants in the democratic process.

Today in a state like Mississippi, because of Freedom Summer and because of the Voting Rights Act, that state has the highest number of African-American elected officials than any state. And if the state were redistricted fairly, in a democratic fashion, there would be several African-American members of the House of Representatives.

Q: What do you mean by that, if it were redistricted fairly?

A: In the state of Mississippi, as in so many parts of America, we’ve had gerrymandering, the drawing of the lines in a way to make it almost impossible for certain people to become elected. They are packing a large percentage of people of a certain race or color in a single district.

Q: Where do efforts to rewrite the Voting Rights Act in a way the Supreme Court would find amenable stand?

A: Today we have a piece of legislation pending that has been supported by both Democrats and Republicans. We don’t at this time have enough members. We are going to continue to work and it is my hope that when we come back in the next congress we will be able to get that support and get it passed through committees and get it on the floor of the House and get it through the Senate.

Q: What is the main thing keeping enough congressman and women from supporting it?

A: I think people from the other side are somewhat reluctant to do anything before this next election. They have to get this election behind them and then (we’ll) do our very best to get the great majority of members on both sides of the aisle from the House to pass it. We pass it on the House side, the Senate will follow.

Q: We’ve seen a rise in laws considered by some to be voter suppression laws, we see what’s going on with Moral Mondays in North Carolina, and other actions people see as rolling back civil rights gains. I asked my Twitter followers in light of this, what would they like me to ask you. One question I received is whether there is a need for another Freedom Summer.

A: There is an ongoing need for another Freedom Summer. We need to organize, to mobilize another generation of people and not just young people, not just college students, to get out there and organize and mobilize and register and empower those who need to be registering to vote. If we fail to do it, we can go backwards. We have made too much progress to go backwards or to stand still. We must move forward.

Direct action is always effective. When you see people standing up, standing in, when you see people marching in an orderly, peaceful, nonviolent fashion – and we did march in Mississippi, we did walk, we did get arrested and go to jail in an orderly, peaceful, nonviolent fashion – there is not anything more powerful than finding a way to make it plain. To make it simple.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Comments powered by Disqus