Series: Roots of an Outbreak

How the Next Pandemic Could Start

ProPublica is a nonprofit newsroom that investigates abuses of power. Sign up to receive our biggest stories as soon as they’re published.

This story discusses pregnancy loss.

Part One

Meliandou, Guinea

We’re investigating the cause of viruses spilling over from animals to humans — and what can be done to stop it. Read more in the series →

Part One

Meliandou, Guinea

We’re investigating the cause of viruses spilling over from animals to humans — and what can be done to stop it. Read more in the series →

Generations ago, families fleeing tribal violence in southern Guinea settled in a lush, humid forest. They took solace among the trees, which offered cover from intruders, and carved a life out of the land. Their descendants call it Meliandou, which elders there say comes from words in the Kissi language that mean “this is as far as we go.”

By 2013, a village had bloomed where trees once stood — 31 homes, surrounded by a ring of forest and footpaths that led to pockets residents had cleared to plant rice. Their children played in a hollowed-out tree that was home to a large colony of bats.

Nobody knows exactly how it happened, but a virus that once lived inside a bat found its way into the cells of a toddler named Emile Ouamouno. It was Ebola, which invades on multiple fronts — the immune system, the liver, the lining of vessels that keep blood from leaking into the body. Emile ran a high fever and passed stool blackened with blood as his body tried to defend against the attack. A few days later, Emile was dead.

On average, only half of those infected by Ebola survive; the rest die of medical shock and organ failure. The virus took Emile’s 4-year-old sister and their mother, who perished after delivering a stillborn child. Emile’s grandmother, feverish and vomiting, clung to the back of a motorbike taxi as it hurtled out of the forest toward a hospital in the nearest city, Guéckédou, a market hub drawing traders from neighboring countries. She died as the virus began its spread.

Emile was patient zero in the worst Ebola outbreak the world has ever seen. The virus infiltrated 10 countries, infected 28,600 people and killed more than 11,300. Health care workers clad head to toe in protective gear rushed to West Africa to treat the sick and extinguish the epidemic, an effort that took more than two years and cost at least $3.6 billion. Then, the foreign doctors packed up and the medical tents came down.

This has long been the way the world deals with viral threats. The institutions we trust to protect us, from the World Health Organization to U.S. agencies like the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, focus on responding to epidemics — fighting the fires once they have begun, as if we could not have predicted where they would start or prevented them from sparking.

But looking back, researchers now see that dangerous conditions were brewing before the virus leaped from animals to humans in Meliandou, an event scientists call spillover.

The way the villagers cut down trees, in patches that look like Swiss cheese from above, created edges of disturbed forest where humans and infected animals could collide. Rats and bats, with their histories of seeding plagues, are the species most likely to adapt to deforestation. And researchers have found that some bats stressed out by habitat loss later shed more virus.

Researchers considered more than 100 variables that could contribute to an Ebola outbreak and found that the ones that began in Meliandou and six other locations in Uganda and the Democratic Republic of Congo were best explained by forest loss in the two years leading up to the first cases.

It is now clear these landscapes were tinderboxes for the spillover of a deadly virus.

We wondered what the world had done to keep disaster from striking again. Had global health leaders channeled money into stopping tree loss or deployed experts to help communities learn how to sustain themselves without cutting down the forest?

To get a sense of the current risk of spillover from deforestation at these sites, ProPublica consulted with a dozen researchers for its own analysis, which was unprecedented in its quest for specific, real-world findings. Using a theoretical model developed by a team of biologists, ecologists and mathematicians, we applied data on tree loss from historical satellite images taken between 2000 and 2021 — the most recent year available — and tested tens of thousands of infection scenarios.

The results were alarming: We found that the same dangerous pattern of deforestation has increased around Meliandou in the past decade, putting its residents at a greater risk of an Ebola spillover than they faced in 2013, when the disease first ravaged their village.

We ran the model for five other epicenters of previous Ebola outbreaks in Uganda and the Democratic Republic of Congo. In four of the locations, that telltale pattern of tree loss got worse in the years since those outbreaks, raising their chances of facing the deadly virus again.

“I think this is very powerful,” said Raina Plowright, a professor of disease ecology at Cornell University and senior author of the model, who reviewed ProPublica’s findings. “Even though we know the fundamental driver of these outbreaks, we have effectively done nothing to stop the ignition of a future outbreak.”

ProPublica traveled to Meliandou, where on the ground, a stark picture emerged. It’s not just that the same conditions remain that primed Meliandou to kindle the worst Ebola outbreak in history.

We found they’ve gotten worse.

It takes a half-hour to walk from the homes of Meliandou through the forest to the denuded mountainside where each family is assigned a plot of land to farm. The cacophony of village life gives way to the hum of insects as residents trek up the dirt path, some balancing basins of water on their heads. Not even the children are exempt from the work it takes to clear the ground for planting. It goes on from dawn to dusk, every day but Sunday, heedless of the heat. You know you’re close to the farms when you start to hear the sound of metal striking the earth.

One day last summer, a 7-year-old boy beat a piece of scrap metal between two rocks, forming it into the head of a hoe, then raced up the slope to join other young workers. Jiba Masandouno, the village chief, followed them, sprinkling rice seed where the land was freshly bare.

These are not the terraced rice paddies that rise like stairs for giants in postcards from Asia. Farming here is very time consuming and difficult, with steep slopes prone to erosion. Many farmers in the U.S. use controlled irrigation, mechanization, fertilizers and products to kill pests and disease. In Meliandou, everything is done by hand, and farmers are at the mercy of the weather and depleted soils, with no room for error. If a field produces a decent harvest one year, they’ll plant it again the next. If it doesn’t, the farmers cut down or burn another patch of forest.

The majority of emerging infectious diseases originally came from wildlife. Many might picture places with caged animals as the spots most primed for a novel virus to spread to humans. After all, one of the leading theories about the origin of COVID-19 is that the virus jumped to humans at a market that sold wild animals in Wuhan, China, and health authorities now are worried about the pandemic potential of a bird flu that swept through a mink farm in Spain last fall. But scientists have shown that land-use change, especially clearing forests for agriculture, is the biggest driver of spillover.

In Borneo, deforestation has brought macaques closer to humans; researchers believe that’s seeding outbreaks of what’s known as monkey malaria. In Australia, the clearing of eucalyptus trees pushed bats closer to homes and farms, spurring the spread of the brain-inflaming Hendra virus. And Nipah, another virus that causes the brain to swell, killed more than 100 people in Malaysia in the late 1990s, after slash-and-burn agriculture forced bats closer to hog farms, and the virus jumped first to pigs and then to humans. That horrific outbreak was fictionalized in the movie “Contagion.”

Researchers have also found that it’s not just the amount of forest cut down but the pattern of deforestation that matters. Models have shown that the more patchy a forest gets, the more edges are created at the borders of clearings where virus-carrying animals can come into contact with humans, until so much forest is cut down that it can’t sustain wildlife anymore. The theoretical model we worked with encapsulates this concept to assess risk by considering the amount of “edge” produced by deforestation. Cutting one big chunk out of a forest would create less edge than cutting out many holes.

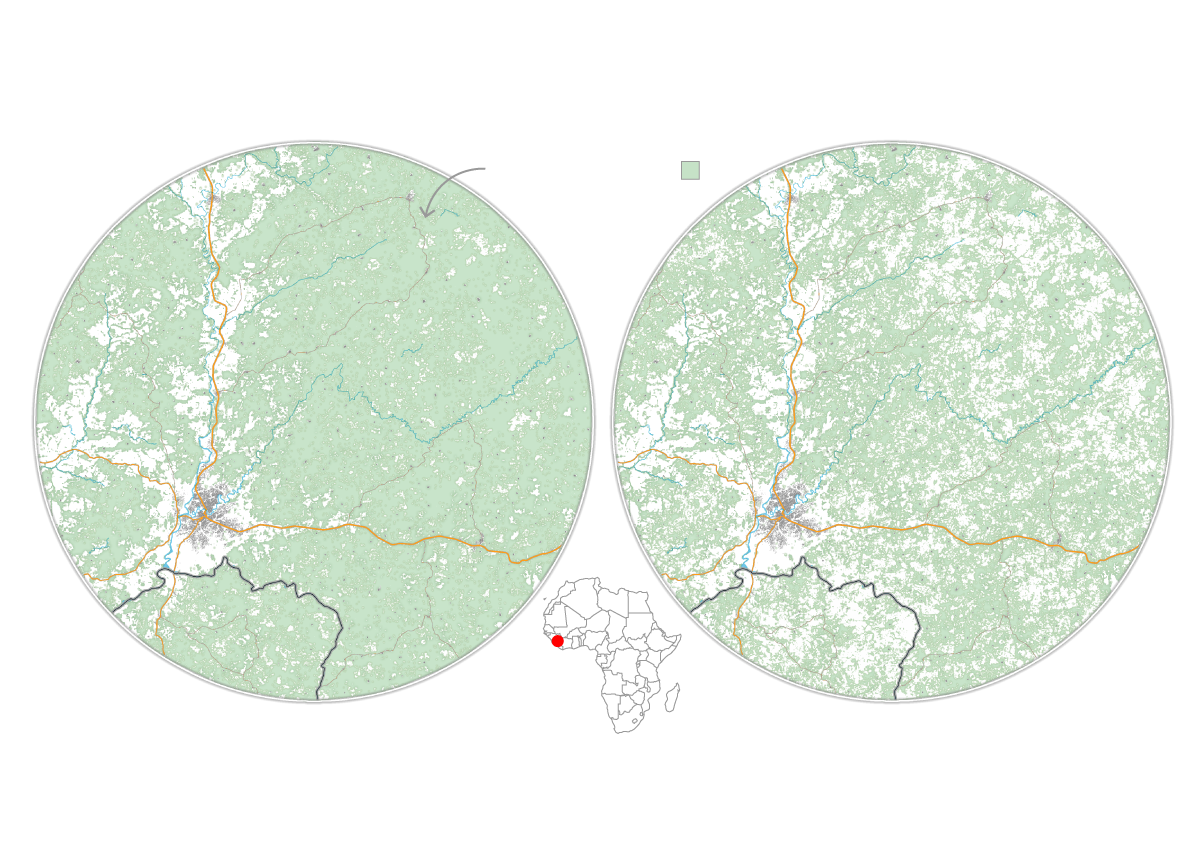

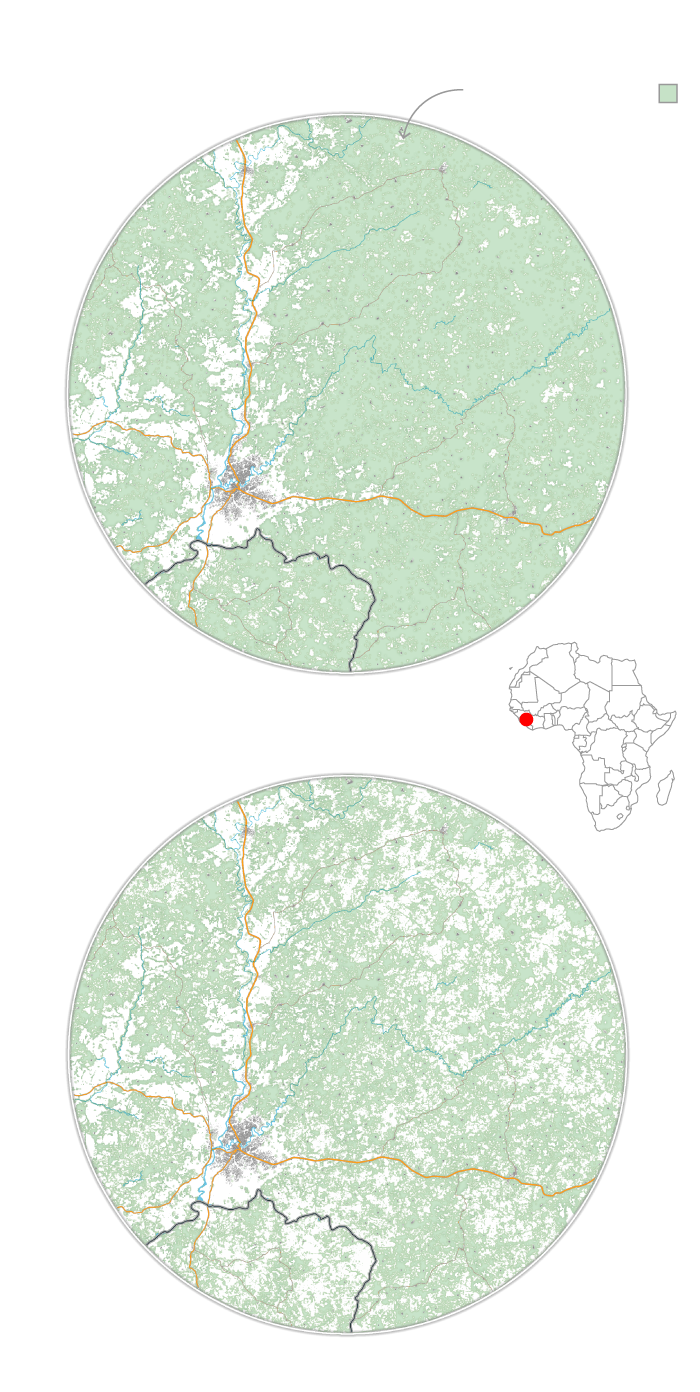

The chance of spillover is higher where people and animals overlap, which the model assumes is along the edge of cleared forest patches. We estimated the size of these “mixing zones” within a radius of 20 kilometers, or about 12.5 miles, from Meliandou. Experts told us this was a reasonable distance for a person there to cover on foot or bicycle. We found that as the forest around Meliandou got more fragmented, the mixing zone area increased sharply, by 61% from 2013, the year the epidemic began, to 2021.

Meliandou’s Forests Have Become Patchier Since the Last Ebola Outbreak

2013

2021

Remaining forest

GUINEA

GUINEA

• Meliandou

• Meliandou

• Guéckédou

• Guéckédou

LIBERIA

LIBERIA

2013

Remaining forest

GUINEA

• Meliandou

• Guéckédou

LIBERIA

2021

GUINEA

• Meliandou

• Guéckédou

LIBERIA

While the model does not calculate the absolute risk of spillover — factors like population density and human behavior are not considered — it shows that the potential for an outbreak starting has increased due to growing patchiness of the surrounding forest. (For more details, read our methodology.)

Last summer, the mountainsides around Meliandou were dotted with light green rice shoots punctuated by tree stumps. The elders there reminisced about the lush forest they grew up in. They hated to see it shrinking, but they said the trees were a necessary sacrifice. The 2021 harvest was meager, so the village did not have money from rice sales to buy fertilizer or pesticide for the crop planted in 2022. Fearful of famine, they cleared more of the forest for farming. Some families also supplement their income by chopping down even more trees to make charcoal they can sell.

Despite the billions spent on recovery from the outbreak that began here, no one has helped the farmers adopt methods that could lessen their risk of spillover.

ProPublica shared with rice farming experts photos of the Meliandou villagers at work and asked what could be done to help them grow food without constantly clearing more of the forest. Mamadou Billo Barry, a retired researcher with the Agronomic Research Institute of Guinea, said those subsistence methods yield only about 1 metric ton of rice per hectare. In neighboring Mali, where the environment is kinder to rice growers, average yields are 4 to 6 metric tons per hectare with potential for 10. What’s more, 75% to 80% of the cultivated land in Africa is degraded; in Meliandou, the fragile soil can lose essential nutrients and organic matter after a year or two of planting.

Experts said that one way to improve the soil’s fertility is to plant cover crops, which add nitrogen to the soil, are left to decay in the fields and slow soil erosion. Erika Styger, a professor of tropical agronomy at Cornell University, said the villagers could divide the fields into sections and rotate what’s planted in each area — rice one year, cassava the next — then let that section rest with cover crops for several years. This, along with targeted fertilizer application, could increase the organic matter in the soil and gradually triple or quadruple their yields compared with what they’re harvesting now.

The bigger expense would be to support an agricultural specialist to build trust with the farmers and figure out what works best so they can avoid clearing more of the forest. A program in Madagascar, which set out not to prevent spillover but to save trees, has succeeded in doing this.

The world has produced more than 40 reports on what went wrong during the epidemic that began in Meliandou and how to avoid similar disasters in the future. Yet Barry, the Guinean farming expert, said the authors of those reports never asked him or his colleagues for advice.

But the link between farming and health is always on the mind of Masandouno, the village chief, whose brow seems permanently furrowed in an expression of concern. As he strides up and down the slope, flinging handfuls of rice seed, he is aware that any excess crop can be sold to pay for medications. He remembers neighbors who have died in recent years of appendicitis and hernias and during childbirth, unable to afford going to the hospital because their harvest was too bare. He knows that villagers, especially children, catch rodents in the forest to fill their bellies, despite the fact that rats in Guinea can carry Lassa fever, which can cause deafness and death.

“We are suffering,” Masandouno said with a tired gaze. “The government has forgotten us. The international community has forgotten us.”

The failure to imagine ways to prevent spillover is rooted in who gets a chance to weigh in when it’s time to make policies and spend money to protect the world from the next big one.

After the Ebola epidemic, Suerie Moon, co-director of the Global Health Centre at the Geneva Graduate Institute, helped lead one of the more influential studies of what needed to change to avoid another epidemic. The 2015 report focused on preparing for and responding to outbreaks, she said, because that was the expertise of the people in the room, including policy wonks fluent in global crises, infectious disease epidemiologists and a representative from Doctors Without Borders, the nonprofit that sent medical workers to the epicenter of the outbreak. Experts in agriculture, conservation and ecology — those most attuned to the forces that drive spillover — were not present, and they are largely excluded from conversations about how to spend pandemic prevention money.

Though the research tying deforestation to outbreaks has piled up since then, the mindset hasn’t changed. The Biden administration’s pandemic preparedness plan, published in September 2021 after COVID-19 had ripped across the globe, identified five areas for action — all of which focused on responding to an outbreak that has already begun. And the International Health Regulations, established by the WHO to govern how the U.S. and nearly 200 other countries address infectious threats, are “largely built on the assumption that disease outbreaks cannot be prevented, only contained and extinguished,” Moon and her co-authors wrote in an article calling for more investment in prevention.

The U.S. has invested in preventing spillover, but its most notable projects haven’t attempted to stop the kind of deforestation that can lead to outbreaks.

In 2009, the U.S. launched what became a 10-year, $207 million project called PREDICT to serve as an early warning system for contagions emerging from the wild. The idea was to identify possible threats and give the world a head start in responding if one of those pathogens jumped to humans. The project discovered 949 novel viruses extracted from bats and other wildlife, trained thousands of people to do disease surveillance and strengthened more than 60 labs across Africa and Asia. Though it assessed risks of deforestation, PREDICT wasn’t designed to stop tree loss. After Ebola burned through West Africa, the program searched for wildlife that transmit the virus and, to help communities reduce their risk, created and distributed a picture book called “Living Safely with Bats.”

Despite its emphasis on virus hunting, PREDICT didn’t identify the coronavirus that sparked the COVID-19 pandemic. And one of its core partners became embroiled in controversy for collaborating with researchers at the Wuhan Institute of Virology in China on risky experiments that manipulated coronaviruses to gauge their spillover potential, using a grant from the National Institutes of Health.

A federally funded successor program called Stop Spillover briefly considered planting trees in one Ugandan district to entice bats away from homes to prevent Ebola and a related virus called Marburg. But potential problems emerged, among them that bats pollinate the cacao crops that villagers rely on for income and drawing them too far away could hurt the harvest. Instead, the program has focused on decreasing contact between people and bats, partly by teaching residents how to keep the creatures and their excrement out of food, water and homes.

Whether it’s Ebola or COVID-19, the way the world responds when viruses ricochet across the globe has a predictable rhythm. In public health circles, this is known as the “cycle of panic and neglect.” At the end of every major outbreak, nations panic and vow to do what’s needed to do better the next time. But after the shock fades, so too does the commitment. The pot of money often winds up far smaller than what was initially recommended, leaving various groups to fight over the scraps.

After the Ebola epidemic, the world invested in virus-testing equipment and training scientists so that African countries could identify contagions as soon as cases popped up. Guinea’s lab infrastructure has improved dramatically; elsewhere, capacity dwindled as resources faded. Dr. Marcel Yotebieng, a New York City infectious disease researcher who often works in the Democratic Republic of Congo, said he often arrives to find equipment in need of maintenance due to a lack of sustained funding. At a lab where he does HIV testing, samples from infants have been known to sit for two years.

There are signs the cycle is repeating now in the denouement of the COVID-19 crisis. G20 countries last year agreed to set up a global fund for pandemic prevention, preparedness and response. The World Bank and the WHO estimate that $10.5 billion is needed annually, and the fund is expected to run for eight years. But as the world focuses on returning to pre-pandemic life, countries and major philanthropies so far have pledged just 15% of the original goal.

At first, it looked like prevention might finally get its day. In a report last fall, staff at the World Bank championed investments in preventing spillover, including suggestions for curtailing deforestation in biodiversity hot spots around the globe. But the World Bank announced in December that the first round of money in the Pandemic Fund will go to the usual things: disease surveillance, laboratories and hiring public health workers.

The jockeying for money began early. Experts convened at the request of the WHO acknowledged that deforestation was leading to more collisions between humans and wildlife, but last June, they argued that spending much of the fund on spillover would be a waste of money. The “almost endless list of interventions and safeguards” needed to do so, they said, was so vast, it was akin to “attempting to boil the ocean.”

Scientists warn that this defeatist attitude is setting our world up for another catastrophe. Studies have shown that spillover events are increasing. In Guinea and other parts of Africa, new roads are being built every day, making it easier for someone to travel from a remote village to a major city. The chances of a spark igniting a multicountry blaze is higher than ever.

The experts convened by the WHO are not wrong about the gargantuan effort it would take to reduce the chances of spillover worldwide. Some researchers have estimated that putting a dent in global deforestation alone would cost up to $9 billion a year, but they argue that the expense would be a drop in the bucket compared with the hundreds of billions of dollars in economic losses from outbreaks each year, not to mention the cost of lives lost.

Nobody knows how many other Meliandous are out there, swaths of forest pocked with enough holes, and shared by enough people and wildlife, for a virus to break into humanity. But we do have a rough sense of where these places might be. The World Bank and the United States government have funded heat maps that can be used to target such places for long-term research and resources.

Instead of worrying about doing everything everywhere, the international community could have started small. A medical desert frequented by disease-carrying bats, Meliandou could have been a testing ground, a chance to make an outsized impact.

A visitor would think that the world invested heavily in Meliandou. At its entrance, a long-departed aid group erected a sign that boasts of the village’s recovery, listing accomplishments including “community resilience to epidemic diseases, the sustained resumption of education, community protection of vulnerable children, the restoration of social cohesion and economic recovery.”

Those who live there consider the sign a bitter joke. Though the group helped them build a school, there’s still no running water or electricity. Etienne Ouamouno, whose toddler Emile was the first to die, is tormented by the reality that, should one of his surviving children get sick today, Meliandou remains just as ill-equipped to help.

Before the disease struck, Ouamouno was known in the village as a charismatic young man, someone the elders said they could count on to lead work projects. But there is only so much pain someone can take. “Emile was everything to me,” he said, a long-awaited son after four daughters. He lost two children in eight days. Then his pregnant wife began to bleed. The midwife shooed him out of the house. Grasping for hope, Ouamouno thought that perhaps the stillbirth could mean his wife, his childhood sweetheart, would be spared. But, he said, “I learned from the cries of the women that my wife had also died.”

Ouamouno became “like a fool,” he said, tempted to run but with nowhere to go. He felt abandoned by everyone. His neighbors shunned him, terrified that they would be next. They only called on him to help bury their dead. Then, the foreign aid groups who promised all sorts of help moved on as Ebola spread into more populous towns.

Today, his resting face is grim; his demeanor, anxious and withdrawn. He didn’t make it to the village chapel on a Sunday last summer as the preacher said, “God is the only one who can give us support when we are abandoned by all.” He didn’t participate in the moment of silence the congregation held that day for their dead, as they have every Sunday in the nine years since Ebola arrived. Ouamouno wanted to hear nothing more about the virus that destroyed his life. He disappeared into the forest, heading to his farm.

If Ebola or another deadly disease emerges from that forest today, it will fall to Catherine Leno to spot it. The 25-year-old midwife, with a sweet voice and a warm, motherly demeanor, is the sole health care provider for Meliandou and also sees patients from more than 20 neighboring villages. The job comes with serious risks: One of her predecessors died of Ebola. Her clinic has three patient beds and a birthing room with a bare mattress, stirrups and a single IV pole. There are a couple of solar-powered lights, which Leno uses sparingly. Outside is the only bathroom in Meliandou, an outhouse with tiles placed around two holes in the ground.

When patients arrive, they wash their hands in the same bucket. Leno weighs them, takes their temperature and jots details of each visit by hand in a record book with a tattered yellow cover. Medication is stacked in a wooden cabinet: malaria treatments, one kind of antibiotic and common remedies for fever, dehydration and stomach troubles, as well as medicines to control excess bleeding in childbirth. She obtains the medicines on credit from Guinea’s Health Ministry, sells them to patients, then pays back the ministry at the end of the month. Leno said she picks drugs that she knows people can afford, eschewing treatments that are more effective but more expensive. She worries they will expire in her cabinet if patients can’t pay for them, leaving her on the hook for the bill.

Magassouba N’Faly, the former head of the hemorrhagic fever lab in Conakry, a full day’s drive away from Meliandou, told ProPublica he was optimistic that Guinea could respond quickly to a new outbreak of Ebola or other infectious diseases. There are 38 infectious disease treatment centers now, he said, one for each district, stocked with personal protective equipment and syringes. Guinean health authorities were able to intervene quickly when lab workers in 2021 detected a case of Marburg virus, a cousin of Ebola. “For our country, we are quite ready to respond to anything,” N’Faly said. Though he still works as a technical adviser to the lab, last summer a new director was installed after a military coup.

Leno’s clinic looks nothing like the new treatment centers — she has no such PPE. During a visit to the clinic last June, there weren’t even any masks in her cupboard; the ones she distributed to villagers earlier in the COVID-19 pandemic were used up long ago. “We’re not prepared,” she said. “If I have certain equipment, I can try my best to a certain level, but if not, I will call for an ambulance.”

The ambulance from Guéckédou can take up to an hour to arrive, slowed by the jolting dirt road. Sometimes it doesn’t come, and Leno’s only option is to take the patient herself, calling a motorbike taxi to carry her and a patient together into town — potentially setting off the same chain of transmission that allowed Ebola to tumble unannounced into the more populous areas of the country.

One thing in Meliandou has changed. The hollowed-out tree is gone, set ablaze by the community. Its decayed stump has been swallowed by the forest. But the bats remain. Hundreds of them return to Meliandou every fall after the rainy season. They found a new tree, this one even closer to the residents’ homes. It towers by the entrance to the village, a few paces off the dirt path, just opposite the sign that promises that after Ebola, everything got better.

Read More From Our Series

Roots of an Outbreak

View All

Just Read

Part One

On the Edge: The Next Deadly Pandemic is Just a Forest Clearing Away

Do You Have a Tip for ProPublica? Help Us Do Journalism.

Got a story we should hear? Are you down to be a background source on a story about your community, your schools or your workplace? Get in touch.

Lylla Younes and Gabriel Kamano contributed reporting. Translation by Youssouf Bah, Gabriel Kamano, Zujian Zhang, Sia Maria Justine Teinguiano. Photo editing by Peter DiCampo. Design and development by Anna Donlan. Illustrations by Katherine Lam.