When it comes to politics, there’s nowhere like Illinois. Throughout the election season, ProPublica Illinois reporter and political junkie Mick Dumke will analyze the state’s political issues and personalities in this occasional column.

If video killed the radio star, big money is sealing the fate of the old Democratic machine.

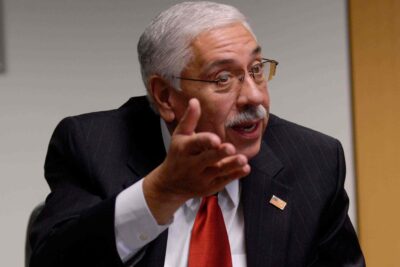

Cook County Assessor Joe Berrios, one of the last remaining machine bosses, conceded early Tuesday night to a political newcomer, a nobody, as the old pols used to say. Fritz Kaegi’s apparent victory — pending a possible court challenge by a third candidate to void the election — came after he vowed to fix what has been exposed as a faulty assessment process, one that burdens lower-income property owners while helping the wealthy.

But Kaegi wasn’t just any reformer promising to clean up this town. He delivered his message by pouring more than $1.5 million of his own money into his campaign.

As the assessor’s race unfolded over the last several months — and especially as the results began to come in last night — I kept thinking about how Berrios got his start in politics nearly 50 years ago: His alderman used clout to get rid of a speeding ticket for him.

It wasn’t his first ticket, and Berrios, then 17, was worried about losing his driver’s license. That would have been a serious financial blow to him and his working-class family, he said in a 2016 interview with me and Ben Joravsky of the Chicago Reader. Berrios’ parents were from Puerto Rico, and during his early years, his family lived at the Cabrini-Green public housing development before moving to the Humboldt Park neighborhood.

At a neighbor’s urging, Berrios mentioned the ticket to his precinct captain, one of those guys who’d been given a government job in return for keeping residents happy and getting them to vote for the machine. The precinct captain took Berrios to meet the boss of the 31st Ward, Alderman Tom Keane.

Berrios said he had no idea Keane was one of the most powerful men in the city, controlling not just his Northwest Side ward but the entire City Council as the right-hand man to Mayor Richard J. Daley. As Berrios stood before Keane’s desk, the alderman noted that the neighborhood was changing. He suggested Berrios volunteer for him.

“He said, ‘You know, we’re looking for some Hispanic kids to join the organization,’” Berrios recalled. Berrios understood that Keane was offering him a deal: You help me connect with Hispanic voters and I’ll help you take care of your speeding ticket. Berrios agreed.

Sure enough, when Berrios showed up for his court hearing, the judge immediately found him not guilty. “I was amazed,” Berrios said. “And that’s how, really, I got started in the game.”

Berrios, worried about finding work when he finished school, was happy for the chance to join the machine. He said his first patronage job was cleaning bathrooms in Humboldt Park.

“You’d be surprised, under the old system, how many people we were able to help on a day-to-day basis,” Berrios said. “Most Hispanics didn’t finish high school back then. It created opportunities for people who would not have had an opportunity.”

But the system also enabled corruption. In 1974, Keane was convicted in federal court of mail fraud for a scheme involving the purchase of tax-delinquent land in city auctions. He then installed his wife as alderman while the ward organization was run by a former aide — who ended up going to federal prison, too.

Meanwhile, Berrios rose through the ranks. In 1983, he became the first Hispanic to serve in the Illinois General Assembly. By 2007, he was chairman of the Cook County Democratic Party, and three years later, he was elected assessor. He also is an owner of a firm that lobbies government officials.

Following in Keane’s tradition, Berrios used his positions to put family members on the public payroll.

Yet his grip on power began slipping. Federal court decrees prohibit political hiring and firing for most local government positions, and the ward organizations don’t have as many jobs to hand out. Many voters are sick of insiders profiting off the system.

Few people thought rookie candidate Will Guzzardi had even a faint chance when he challenged incumbent state Rep. Toni Berrios, Joe’s daughter, in 2012. But Guzzardi came within 125 votes. Two years later, Guzzardi beat her handily after going door to door for months to talk with voters.

“I think we were able to show that the Berrios machine was really a paper tiger, and that they really didn’t have the strength everyone assumed,” Guzzardi told me in an interview last week. “People were really fed up with that brand of politics and wanted something different.”

Through it all, Berrios continued to brush off his critics. In speaking about the operations of the assessor’s office, he sounded a little like Mussolini boasting about the trains: “After one year in that office, I got the tax bills out in time,” he said, estimating this saved local governments millions of dollars in borrowing costs.

But Berrios appears to have gotten the bills out on time because thousands of commercial and industrial properties weren’t being assessed, as my colleagues Jason Grotto and Sandhya Kambhampati found in months of reporting. In short, the assessor’s office wasn’t doing its job.

Kaegi, a financial asset manager, ran for the right office against the right guy at the right time. He depicted his quest as a social cause as much as a political campaign — even as he engaged in the old-school power play of trying to knock a third candidate, Andrea Raila, off the ballot. A state appellate court ruling kept her in the race, but some voters were told their ballots for her wouldn't count, prompting Raila to call for a new election.

This wouldn’t have happened when the machine was humming.

For now, Kaegi is the winner — and Berrios is the clear loser. It remains to be seen if Kaegi will follow through on his vows to clean up and restore confidence in the assessment system. Voters are hopeful, and quite frankly, the bar is low.

Only a couple of the old-school bosses are left. As the machine dies off, the void is often filled by people with the finances and friends to purchase a pathway to office — as we’ve seen with Mayor Rahm Emanuel, Gov. Bruce Rauner and J.B. Pritzker, the Democratic nominee for governor.

Berrios noted the trend when asked about his practice of accepting campaign contributions from lawyers with appeals before his office.

“I am not the governor,” he said. “He can just flip the money out any way he wants to. I need to go out and solicit contributions.”

It was a weak excuse for engaging in pay-to-play politics. But it doesn’t mean Berrios was wrong about some of the new bosses getting rid of the old ones.

Filed under: