ProPublica is a nonprofit newsroom that investigates abuses of power. Sign up to receive our biggest stories as soon as they’re published. Having issues voting? You can tell us about it or read ProPublica’s voting guides in English and Spanish.

As COVID-19 cases have soared in suburban St. Louis County, Missouri, so have the calls from ailing or quarantined voters to the Board of Elections, asking how they can vote. Until this week, workers have taken down their contact information and sent ballots to their homes. But on Monday, the board pivoted, establishing a drive-thru site. Today, 12 poll workers, including volunteer firefighters and police officers from the local emergency department, are processing voters in two drive-thru lanes.

“So many more people are testing positive, there’s no way we could send them all ballots,” said Eric Fey, the board’s director, estimating that at least 400 or 500 people were unable to vote in person and hadn’t signed up to vote by mail.

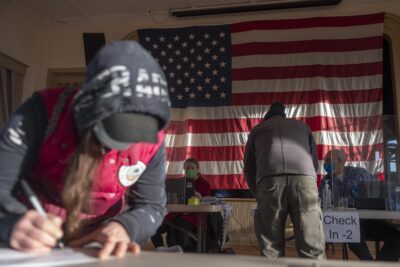

As Americans go to the polls today, they are voting in an election shadowed by public health issues in ways not seen since the midterms of 1918, which were held during a deadly flu epidemic that swept the globe. The last-minute adaptations in Missouri are the latest twist in an unprecedented campaign shaped by a pandemic, vastly expanded mail-in voting, widespread misinformation and the incumbent president’s unfounded allegations of voter fraud and threats not to abide by the outcome. In an election in which about 100 million people have voted early or by mail, the rising number of COVID-19 cases appeared poised to dampen turnout on Election Day itself.

For ProPublica’s Electionland project, hundreds of journalists from almost 150 newsrooms across the country are monitoring Election Day. Scattered instances of apparent voter intimidation, including some by supporters of President Donald Trump, have marred a largely calm and smooth election. For example, a 5-ton truck bearing Trump signs and flags parked near a voting site in Iowa. The occasional aggressive tactics did not appear to be coordinated or to discourage many people from voting. Other problems ranged from broken voting machines in minority neighborhoods to ballot-counting snafus.

It seemed likely that some voters would be disenfranchised because an overwhelmed Postal Service would be unable to deliver their ballots in time. Misinformation, especially on social media, aimed to intimidate people from going to the polls, while the number of polling places in some cities failed to keep pace with rising voter registration, spurring expectations of long lines in minority and low-income neighborhoods where residents predominantly vote in person.

The pandemic has transformed voting across the country. Most of the more than 300 election-related lawsuits filed in 45 states, Puerto Rico and the District of Columbia since March stem from efforts to make voting safer and the ensuing partisan backlash. Late Monday, a federal appeals court rejected a move by Republicans to block drive-thru voting in Texas. Nevertheless, Harris County closed nine of 10 drive-thru polling locations in the Houston area to minimize the number of votes that would be tossed out if the plaintiffs ultimately prevail. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said in a post Monday that people with coronavirus “have the right to vote, regardless of whether they are sick or in quarantine.”

In Hardin County, Iowa, auditor Jessica Lara has set up curbside voting so people who are COVID-19-positive or quarantining can have ballots brought to their vehicles by election workers. Over the past two days, Hardin County has had more than 30 COVID-19-positive people vote curbside, and Lara expects at least 20 more on Election Day.

Every poll worker in Hardin County is receiving gloves, masks and face shields, and as much as possible, is using nonrecyclable items. Every ink pen is being sent home with voters and not reused, Lara said. The county has also obtained large quantities of folders called “secrecy sleeves” that cover two-sided ballots. Normally these sleeves are reused, but this year there will be enough so each voter will have their own.

Lara has also had 10 volunteer poll workers, or 10% of her workforce, drop out because they have tested positive for the virus. She originally planned to have five workers at each polling site, and she’s now down to three or four at each location. “Three is minimum staffing, so we’re still OK, but it’s going to mean longer wait times for voters, and then we’ll have a lot of curbside voting and that means the staff will have to go inside and outside, so that’ll impact the in-person voters,” she said.

Here’s ProPublica’s reporting on the biggest questions about an election like no other:

How Is the Pandemic Affecting the Election?

Though state election rules vary widely, one thing is certain: Voters are going to the polls with the pandemic on their minds. Since April, nearly every month voters have consistently ranked the pandemic as the most important problem facing the country today, according to Gallup.

Spikes in the search term “vote with Covid” reflect areas where COVID-19 is rampant, according to Google Trends, with Iowa, Missouri, Minnesota and Wisconsin topping the list of states where the term has been most searched in the past seven days. The term has been searched five times as often in Iowa than in states like New Jersey or Washington, according to Google Trends.

Since Oct. 20, the U.S. has seen more than 60,000 new cases per day, with more than 97,000 cases reported on Oct. 30, shattering the record of 88,000 set the day before. With more than a dozen states reporting rising case counts, public health experts are characterizing the current surge as a “third wave” of the pandemic in America. From Oct. 1 to Oct. 29, hospitalizations in the swing states of Ohio, Wisconsin and Pennsylvania have more than doubled, according to data from The COVID Tracking Project.

Cheryl Sattler, a 52-year-old attorney in Gadsden County, Florida, signed up to be a poll worker for the first time in her life because of the expected shortfall of older volunteers at greater risk from the coronavirus. During her two-hour training, she learned about pandemic precautions, including the plexiglass barriers that are supposed to protect her and the cleaning device that would decontaminate every pen that voters would use.

During the primaries, she said, her county wasn’t ready. “I was touched by eight people, and it was so icky.” But, she said, it’s better prepared today. As for herself, the election is so important that she feels compelled to volunteer, she said. “I’m healthy, so I’m going to take my chances.”

Can the U.S. Postal Service Handle Tens of Millions of Mail Ballots?

With tens of millions of people voting by mail for the first time, election officials have spent months warning about postal delays.

In the days leading up to the election, the Postal Service has delivered increasingly fewer ballots on time in key battleground states. In Philadelphia, for example, 42% of all first-class mail is taking more than five days to be delivered. Last week, on-time deliveries for first-class mail dipped as low as 42% in Detroit, 56% in Wisconsin and 53% in South Florida. (USPS has asserted that daily figures fluctuate, and that on-time performance measured by week is much better.)

“It’s painting a pretty bad picture,” said Ivan Butts, health resource manager at USPS and executive vice president of the National Association of Postal Supervisors. Realistically, he said, the time to get ballots in the mail was a week before the election, which is in line with the Postal Service’s official advice to voters. He said it’s hard to say whether everyone’s votes are going to be counted. “I guess it’s going to be up to courts.”

Last week in Miami-Dade County, inspectors found 62 undelivered ballots sitting in a post office among 180,000 pieces of delayed mail. After the discovery, agents from the USPS Office of Inspector General searched other facilities in the county for more ballots, and a U.S. Southern District of Florida judge ordered the Postal Service to certify that there are no ballots left behind.

In light of the much slower delivery times, on Friday a U.S. district judge in Washington, D.C., ordered the Postal Service to take “extraordinary measures” to expedite ballots. Today, the judge ordered the Postal Service to sweep its processing facilities for ballots in 12 districts including Central Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Detroit, Atlanta, Houston, South Florida, Greater South Carolina and Arizona. Any ballots identified need to be sent out for delivery immediately. The Postal Service has to file a status update confirming the sweep and absence of ballots by 4:30 p.m. today.

The Postal Service remained understaffed as coronavirus sidelines employees. To date, almost 15,000 postal workers have tested positive for COVID-19, and 101 have died. Over the last two weeks, the number of positive cases rose by 13%. Last week, about 7,600 postal workers were in quarantine. According to a court filing, COVID-19-related absences have slowed mail in Detroit and greater Michigan, central Pennsylvania, Colorado and Wyoming.

“Everybody’s tired. Everybody’s working a lot of overtime. Everybody’s on edge. And then you say, we need a little more out of you,” said Roscoe Woods, a Detroit-area postal union president. “You can only go at 150% for so long.”

As of Monday, Wisconsin still had 179,700 ballots not yet returned. Last week, the U.S. Supreme Court rejected an attempt by Democrats to extend the deadline to receive absentee ballots until six days after the election. Mail delays or not, ballots must be received by tonight to count.

“There is going to be disenfranchisement,” said Jay Heck, executive director of Common Cause Wisconsin, a nonpartisan public interest group. He expects that the state will see many times more late-arriving ballots than during its spring primary, held during the first surge of the pandemic.

“It’s going to be more difficult for Wisconsinites to vote on Nov. 3 than it was last April,” Heck said.

A USPS spokesperson did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

How Safe Is Our Election Infrastructure?

Analysts from the commonwealth of Virginia and the U.S. Department of Homeland Security are gathering today in an old library reading room in the governor’s executive office in Richmond. Sitting 6 feet apart, and also connected to remote workers via online chat rooms, they will work to detect ongoing threats to election systems and share details of potential attacks.

U.S. officials are working to prevent a repeat of 2016, when Russia hacked the Democratic National Committee and strategically released emails during the presidential campaign’s eleventh hour. That effort promoted media coverage critical of then-Democratic nominee Hillary Clinton. Once again, as another election unfolds, Russian hackers are continuing to try to poke holes in election infrastructure.

They’re hardly alone. In recent weeks, DHS and the FBI warned that Iranian hackers were targeting election websites to obtain voter-registration data, which in some states is public record. Officials said the attackers also probed those sites for weaknesses in security protocols — a more significant threat that could allow them to disrupt the vote or access more sensitive information.

Cybersecurity problems have loomed over America’s election infrastructure for years. Earlier this year, ProPublica found that dozens of election-related websites in counties and towns that had voted on Super Tuesday were particularly vulnerable to cyberattack. In recent weeks, a county elections office in Texas became infected with a type of malicious software that is often a precursor to ransomware, while a ransomware attack penetrated a Georgia county’s networks.

Those kinds of attacks, in which hackers take computer systems hostage in exchange for a ransom payment, are a top concern among federal authorities, officials said. The problem is so concerning that U.S. Cyber Command recently tried to disrupt computer networks used to distribute ransomware. Attacks on election officials’ systems, even if they don’t directly affect voting machines, can cause slowdowns or muddy citizens’ confidence in the process.

The National Association of State Election Directors recently urged officials to be prepared with backup plans but cautioned that hiccups aren’t necessarily the result of malicious activity. “The eyes of the American public and the world are on election officials as we administer free and fair elections during this unprecedented time,” said Amy Cohen, the group’s executive director.

Christopher Krebs, director of the federal Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, said that while U.S. officials are confident that cyber-actors can’t change votes, “that doesn’t mean various actors won’t try to introduce chaos in our elections and make sensational claims that overstate their capabilities.”

How Widespread Is Misinformation About the Election?

Online misinformation has been fueling falsehoods, unfounded warnings and conspiracy theories about the election, much of it aimed at undermining faith in the electoral system and deterring people from voting. Trump has made unfounded allegations of fraud in mail-in voting, which many of his supporters have echoed.

ProPublica and KQED reported Monday that at least two dozen groups on the Chinese-owned social media app WeChat have been circulating misinformation that DHS is “preparing to mobilize” the National Guard and “dispatch” the military to quell impending riots, apparently in an attempt to frighten Chinese Americans into staying home today.

Last week, conspiracy theories circulated in Texas following reports about misprinted barcodes in Fort Worth. The error forced workers to duplicate ballots so they could be rescanned into the system. But the administrative mishap led some right-leaning voices to assume the worst. One post said the incident “should scare voters,” suggesting local officials can’t be trusted to count the duplicates correctly. That and other examples were collected by Junkipedia, a repository that gathers misinformation online.

Social media platforms have made uneven attempts to stop misinformation. Facebook has long banned posts that misrepresent who can vote, whether a vote will be counted and what kinds of documentation must be provided in order to vote. Facebook also blocked new political ads during the week before the election. (Twitter has banned political ads completely.) But ProPublica reported in July that misinformation about voting — particularly voting by mail — continued to flourish on Facebook. And Facebook’s administration of the political ad ban has been uneven, leaving loopholes that have resulted) in false ads being sent to voters.

“All the talk about militias and Antifa and civil unrest — it’s just so easy to spread that stuff online,” said Chris Piper, Virginia’s election director. Officials will have direct lines to social media companies in case large-scale half-truths and lies start spreading like wildfire on the internet. “Everyone’s standing guard,” he said.

Not all misinformation spreads via social media. U.S. intelligence officials say Iran was behind a recent voter-intimidation campaign in which hackers sent threatening emails purporting to be from the violent, far-right group Proud Boys. They also downloaded publicly available voter data and sent registered Democrats threatening emails, in a ham-fisted effort to force them to vote for Trump. Some misinformation efforts have also been delivered by text.

How Long Are the Lines?

At early voting in Columbus, Ohio, the line snaked around a shopping center parking lot as people waited hours to cast their ballots. Philadelphia voters came carrying their own folding chairs. In Texas, where more people have voted early than in all of 2016, people started lining up as early as 5 a.m.

As in previous elections, the lines were expected to be longest in minority and low-income neighborhoods. A 2019 study for the National Bureau of Economic Research used cellphone location data to estimate that residents of Black neighborhoods waited 29% longer to vote in the 2016 election and were 74% more likely to spend more than 30 minutes at their polling place. Researchers at the Brennan Center for Justice at New York University Law School have attributed the disparity to fewer voting machines and poll workers in minority neighborhoods.

“I would be surprised if there weren’t disparities in wait times for early voting and on Election Day in 2020,” said Devin Pope, a professor at the University of Chicago’s Booth School of Business and one of the authors of the NBER paper.

This year, cash-strapped jurisdictions have had to consolidate precincts, recruit younger poll workers and observe social distancing. (Standing 6 feet apart may make lines appear longer even if they’re moving swiftly.) In nine Atlanta-area counties, there are almost 40% more voters per polling place than in 2012 as officials cut precincts despite population growth, according to an analysis by ProPublica and Georgia Public Broadcasting. Voters there waited as long as 10 hours during the first days of early voting.

In West Philadelphia, Rev. Lisa Cross of the Calvary AME Church said several congregants who requested mail-in ballots in October never received them and will have to vote in person. One member went to vote early but was deterred by the long line. “He’s going to try to go today,” she said. “They’re pressing on.”

Eileen Haskell, a library branch assistant in Fort Wayne, Indiana, didn’t meet the criteria for an absentee ballot in her state. She made three trips to early voting locations but was deterred by hourslong waits each time, she said. She’s hoping for better luck at her regular precinct today.

“Obviously we needed more places to vote early or the lines wouldn’t have been so long,” Haskell, 61, said. Voters “shouldn’t be standing outside for an hour.”

How Many Mail-In Ballots Are Being Rejected?

A record number of American voters have already voted, thanks to a massive expansion of absentee voting in states across the country and early voting drives by campaigns. As many as 100 million people could vote early, according to an estimate by Michael McDonald, a University of Florida political science professor who tracks early votes.

For comparison, that’s about two-thirds of the total vote during the 2016 presidential election. Both Hawaii and Texas have already passed their vote totals from four years ago, and 10 other states are at 80% or above.

With more people voting by mail this year comes the potential for more rejected ballots.

In many states, rejected ballots can be fixed. This process is known as “curing” in North Carolina, where more than 928,000 mail ballots have been cast. As of Nov. 2, there were 4,865 mail ballots in the state marked as “pending cure” and about an additional 2,800 with incomplete witness information — together less than 1% of all mail ballots in the state, according to statistics released by the State Board of Elections.

African American voters are more likely to have ballots in need of curing and without witness information in North Carolina. In a state where Black people make up 20% of registered voters, 30% of the “pending cure” ballots came from Black voters. African American and white voters both have about 1,000 mail ballots flagged as missing witness information.

That pattern has repeated itself in other states, including Florida, where voters of color and younger voters are more likely to have their mail ballots flagged for “deficiencies,” according to an analysis by University of Florida political science professor Daniel Smith.

Other states, including Pennsylvania, Michigan and Wisconsin, have rejected a small number of mail ballots, but it’s likely that tally will increase throughout Election Day as election officials in those states begin to process ballots. In addition, mail ballots that arrive after deadlines likely also will be rejected.

More than 3 million voters in Pennsylvania requested a mail-in ballot for the election, a novelty in a state that in previous years has voted almost entirely in person on Election Day. Fewer than 1,000 have been rejected by election officials, mostly from first-time voters who did not provide identification, according to data provided by the state.

Rejections also could stem from changes to election procedures, such as in South Carolina, where a requirement that absentee ballots have a witness was removed then added back, potentially meaning that some voters’ ballots won’t be counted.

Ian MacDougall and Maya Miller contributed reporting.

Filed under: