This story is a collaboration with the Chicago Tribune.

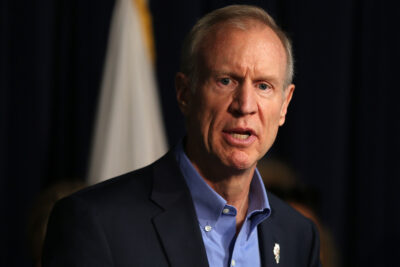

Gov. Bruce Rauner’s executive order seeking to bar state lawmakers from representing clients before a board that hears property tax appeals is largely symbolic, state data suggest, revealing how limited the Republican governor’s options are for changing the system.

Vowing to end what he called a “clear conflict of interest,” the governor cited the Chicago Tribune and ProPublica Illinois’ “The Tax Divide” series in promising to follow up the order with legislation to reform the property tax system in Cook County, as well as across the state.

“We have a deeply flawed and overly complicated property-tax system that recent investigations have shown results in inequitable, disproportionately high property-tax burdens on low-income residents,” Rauner said in a statement. “For any legislator to profit from this system undercuts the public’s faith that they are in office to do what’s best for their constituents.”

“The Tax Divide” found the Cook County assessor’s office often overvalued low-priced properties while undervaluing high-priced ones, ultimately giving unsanctioned tax breaks to wealthier property owners while punishing low-income residents and small business owners.

Rauner’s executive order, issued Friday, was aimed at property tax attorneys who benefit from the county’s flawed system, including his nemesis, House Speaker Michael Madigan.

But barring state lawmakers from representing clients before the Illinois Property Tax Appeal Board is unlikely to trigger much change, because the board does not provide as much relief as other venues open to tax attorneys — especially in Cook County.

Cook County property owners generally appeal their assessments directly with the assessor’s office or turn to the Cook County Board of Review, a three-member panel that also hears appeals. If they are not satisfied with those decisions, they can appeal to the Property Tax Appeal Board — whose five members are appointed by the governor and confirmed by the Senate — or file a property tax objection case in Circuit Court. Most attorneys in Cook County opt for the latter.

The state appeal board, known as PTAB, has heard cases involving about 175,000 parcels of real estate and granted more than $8.7 billion in reductions since 2011. Cook County accounted for nearly 80 percent of the caseload but only about a third of the reductions, according to data from the board’s annual reports.

By comparison, the Cook County assessor’s office granted nearly $19 billion in reductions for 251,000 parcels during that period for commercial and industrial properties alone, according to a Tribune-ProPublica Illinois analysis of county data. Billions more in reductions were granted by the Board of Review.

And while Madigan’s law firm, Madigan & Getzendanner, is one of the most active in Cook County’s appeals industry, data from PTAB show that the executive order would have little impact on the firm’s business.

Between 2000 and 2016, the data show, Madigan’s firm filed appeals at PTAB involving only 780 parcels of property. Between 2011 and 2016 alone, the firm filed appeals with the Cook County assessor’s office for more than 4,000 parcels.

Other lawmakers whose firms could be affected by the order are state Rep. Robert Martwick Jr., a Chicago Democrat, and Senate President John Cullerton, also a Chicago Democrat, whose brother Patrick handles property tax appeals for Thompson Coburn.

Martwick, who works at the law firm of Finkel, Martwick & Colson, where his father is one of the founders, called the executive order “blatantly political.”

“In a citizen legislature, everyone has a conflict of interest,” said Martwick, whose father is also secretary of the Cook County Democratic Party. “But the idea that legislators who are property tax lawyers have any more of a conflict than any other citizen who serves in the legislature is not true.”

In addition, Madigan spokesman Steve Brown said Rauner’s order “tends to pre-empt the idea that a person can hire whoever they want as their own lawyer.” He criticized it as a politically motivated move.

A spokesman said Cullerton’s office is reviewing the governor’s action.

Ann Lousin, a professor of law at John Marshall Law School who is an expert on the state’s constitution, said Rauner’s executive order may have trouble meeting a constitutional test.

“This is almost certainly a violation of separation of powers and a violation of the special legislation clause because he’s making rules regarding the ethical conduct of legislators, which is a separate branch of government,” Lousin said.

The governor’s office said the order is modeled after a state law that restricts lawmakers from representing individuals before the state’s Workers’ Compensation Commission and the Court of Claims, which hears workers’ comp cases.

As word of the order spread, it sparked criticism from property tax attorneys.

“I am outraged by this,” said Chicago-based lawyer Gary Smith. “I understand the governor objects to certain people practicing their profession. But you have to do things like this through legal means. The executive branch should not be writing laws through executive orders.”

Rauner has yet to provide details on what broader legislative changes he would seek. But altering Cook County’s property tax system would require legislation at the state or county level.

State law gives the county almost complete autonomy over how it structures its system, and any attempt to alter the state’s property tax code would be difficult given that Democrats led by Madigan and Cullerton control the General Assembly.

Oversight of the county’s assessment system has also been a challenge because for decades the assessor’s office has considered itself an independent agency that operates outside the purview of the bodies that oversee county government.

The county’s inspector general had to take Cook County Assessor Joseph Berrios — who is also chairman of the Cook County Democratic Party — all the way to the Illinois Supreme Court in order to exert oversight over the assessor’s office.

Earlier this month, the Cook County Board of Ethics fined Berrios $41,000 for failing to return campaign contributions from tax appeals lawyers that exceeded a limit for people who have recently sought official county action.

Berrios is expected to challenge that ruling as well, asserting among other things that the county ordinance is superseded by higher state contribution limits.

This story is not subject to our Creative Commons license.

Filed under: