This story was co-published with WTTW/Chicago PBS. ProPublica is a nonprofit newsroom that investigates abuses of power. Sign up for Dispatches, a newsletter that spotlights wrongdoing around the country, to receive our stories in your inbox every week.

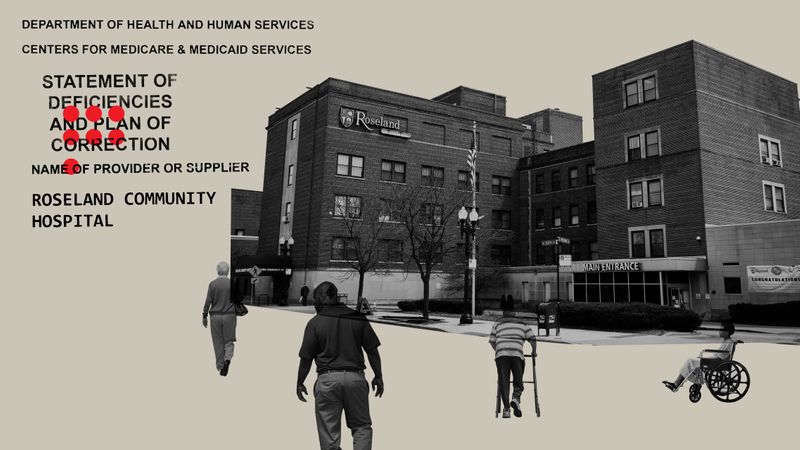

For years, Roseland Community Hospital has been buffeted by complaints about the quality of its medical care and the competence of its management, all while periodically at risk of shutting down. And for years, leaders at the nonprofit facility have defended it, arguing the safety net hospital is essential to the health of residents on Chicago’s South Side.

The hospital’s website is loaded with pithy phrases to reassure patients: Trust us. People come first. We provide best quality care. Always on time.

But federal inspection reports, medical malpractice lawsuits and a whistleblower complaint to the state paint the hospital as putting patients at risk of harm or death, an investigation by ProPublica and WTTW News has found.

Since Jan. 1, 2020, errors or neglect have contributed to the deaths of at least seven Roseland patients, including one who was pregnant, according to federal inspection reports. At least four more deaths during that period have prompted lawsuits against the hospital, with families of patients alleging that their loved ones would be alive if not for the staff’s medical missteps.

Two other deaths are highlighted in a whistleblower complaint that a former Roseland physician filed with the Illinois Department of Public Health. In the complaint, the physician alleges that another doctor who used to practice at the hospital was slow to respond to patients’ medical needs, contributing to their deaths.

The deaths of those 13 patients suggest that conditions at Roseland had become dire — so much so that illnesses that should have been treatable had become potentially fatal and a hospital long dedicated to treating its South Side neighbors safely did not always manage to do so.

Federal regulators have cited Roseland at least 72 times since Jan. 1, 2017, more than any other Illinois hospital that’s monitored by the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

The lapses touched different departments, different employees, different leaders. Nurses and others neglected to consistently monitor patients’ vital signs as they lay slowly dying. Doctors failed to give patients required medical assessments. The pharmacy took hours to fill potentially life-saving prescriptions. In other cases, the hospital failed to maintain equipment and follow infection prevention protocols.

Some of the lapses were serious enough to warrant what federal regulators call an “immediate jeopardy” citation, which flags problems that, if left uncorrected, put patients at risk of harm or death. Since 2017, Roseland has received eight immediate jeopardy citations.

For a hospital to receive even just one immediate jeopardy warning is a “shock,” said Dr. Jose Figueroa, an assistant professor of health policy and management at Harvard University who has researched hospital quality. Getting such a large number in a relatively short period of time “seems really bad,” he said.

Timothy Egan, Roseland’s president and chief executive, declined requests for an interview. But a spokesperson and a top hospital official defended Roseland’s record, saying that it has faced significant challenges over the past several years that were made worse by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Like other safety net hospitals, which treat all patients regardless of their ability to pay, Roseland depends financially on reimbursements from Medicare and Medicaid, which pay for treatments for its low-income, senior and disabled patients.

The spokesperson, Dennis Culloton, and the hospital’s new chief quality officer, Sharon DeVita, declined to comment on particular deaths or about lawsuits brought in connection with those deaths. Court records in Cook County show Roseland denied the allegations in one lawsuit and that another lawsuit was dismissed. Court records do not show any response to a third lawsuit, while in another the hospital has said that under an executive order signed by Gov. JB Pritzker, Roseland should not face litigation stemming from incidents that occurred during parts of the pandemic.

“The entire staff of Roseland Hospital served the disinvested community of the far South Side of Chicago through the global pandemic, the challenges of which the hospital and the community continue to face to this day,” Culloton said in an email. “Severely ill patients from our community presented in our safety net hospital’s Emergency Department and sadly some did not survive.”

DeVita said Roseland’s staff “grieves for the loss of any patient.” But she said the circumstances of the deaths flagged by investigators are less similar than their reports suggest and involve patients with unique health conditions.

Roseland, like hospitals across Illinois, at the time was barred by the state from closing its emergency room since the beginning of the pandemic; that, hospital officials said, contributed to overcrowding and stress on the staff.

“The pandemic,” DeVita said, “strained staffing throughout all healthcare systems, especially urban and safety-net hospitals.” She said some nurses who were contracted by the state to help shore up Roseland’s staff during the pandemic “required significant training.”

Both Culloton and DeVita emphasized that since 2021, Roseland has embarked on a campaign to examine and enhance safety practices across the facility. They said the hospital has also addressed the specific deficiencies cited by regulators.

DeVita said Roseland has “redoubled its commitment to the process of continued improvement.”

A spokesperson for the state public health department said that corrective actions taken by the hospital in the wake of the 2021 immediate jeopardy warnings were “sufficient,” and that all of the warnings have been lifted. Roseland is now in good standing with the state.

But while Roseland’s deficiencies have been addressed, there’s no guarantee that the underlying conditions that caused them have been resolved, according to Lisa McGiffert, a co-founder of the Patient Safety Action Network.

“Not sure there’s anyone looking at these hospitals holistically,” McGiffert said of hospitals in general. “[Regulators] will say, ‘We found infection control breaches in a particular room. … You have to clean up the sinks.’ But if there’s a more systemic problem, just cleaning up the sink isn’t going to fix the issue.”

The last time Melichsia Boss spoke to her father, Wilford, in June 2021, an ambulance was speeding him to Roseland. The 70-year-old former property manager had been picked up at his South Side nursing home after he complained of trouble breathing. Medical records provided by his daughter show that Wilford Boss, who underwent regular dialysis treatments, was found breathing rapidly and somewhat confused.

Still, Boss said, her father was lucid enough to reassure her when she reached him on the phone. It was just some shortness of breath, he told her. She asked the ambulance driver not to take her father to Roseland. His primary care physician practiced at the University of Chicago Medical Center, and as a native Chicagoan, she was aware of Roseland’s reputation.

“They have history,” she said in an interview.

But protocol required that medics take Wilford Boss to the nearest hospital. By the time the ambulance arrived at Roseland’s emergency room, his breathing had worsened and his heart rate had become erratic. Doctors ran tests to find the cause. The attending physician later wrote that, as Boss began to decline, he might need a breathing tube.

But the treating physician delayed inserting a breathing tube as Boss’ lungs failed, despite several pleas by duty nurses to do so, a Roseland physician wrote in a complaint to the Illinois Department of Public Health. Less than eight hours after the ambulance dropped Boss at Roseland, he was dead. The official cause of death was respiratory failure.

The doctor who submitted the complaint, obtained by ProPublica and WTTW News, was named in the records but declined to comment for this story. The news organizations are not naming the whistleblower.

The doctor who treated Boss no longer works at Roseland and declined to comment.

Spokespersons for the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and the state public health department declined to discuss complaints regarding Boss’ death or other deaths, but it appears Roseland was never cited for its treatment of Boss.

Boss’ daughter was unaware of the complaint over her father’s medical treatment, and she began to cry when reporters showed it to her. A year after her father’s death, she said she regrets not involving herself more in his care.

“I wish I’d never let them take him to Roseland,” she said.

Roseland opened in 1924, one of several hospitals established to serve growing populations of immigrants settling on Chicago’s South Side. The area was once solidly middle class. But as factories shuttered, companies disinvested and crime increased, a number of the communities surrounding Roseland slid into poverty. Over time, the hospital increasingly struggled financially. Today its service area spans 12 predominantly Black neighborhoods and six ZIP codes.

The hospital and its advocates have often complained that reimbursements from Medicare and Medicaid are slow to arrive, forcing Roseland — as well as other safety net facilities — to operate on slim financial margins.

Nearly 92% of patients admitted to Roseland in 2020 received Medicare or Medicaid, according to state reports. That’s a far larger percentage than the statewide number, which shows that 66% of all Illinois hospital inpatients relied on those benefits. Regardless of their method of payment, for many South Side residents, Roseland is the only option. The next nearest hospital is several miles away.

In 2013, budget woes forced Roseland to the brink of closure. That year, the hospital laid off nearly 70 employees amid a messy fight with then-Gov. Pat Quinn over millions of dollars in allegedly unpaid reimbursements, with accusations of mismanagement lobbed back and forth between the two sides.

A $350,000 grant from the state helped the hospital avert closure. Then-president and chief executive Dian Powell stepped down that June after less than two years on the job amid accusations of mismanagement and after stating incorrectly that the state owed Roseland $6 million. Powell denied any mismanagement but said she was mistaken about the amount the state owed Roseland.

Egan was made Roseland’s chief executive in 2014 after initially being brought on to stabilize hospital finances. But Roseland continued to struggle. In January 2018, Roseland officials announced another round of layoffs. This time, 35 workers, about 7% of the hospital’s 500 employees, were terminated in an effort to cut costs, officials said at the time. Dozens of employees, including some executives, saw their salaries temporarily reduced.

Federal tax documents filed in February 2018 show that the hospital’s operating deficit reached $7.5 million. Four years later, Roseland reported just over $11 million in surplus, the records show.

Federal investigative reports make it clear that the pandemic further stretched an already-thin medical staff.

Regulators have cited Roseland three times since 2017 — including twice since 2020 — for failing to ensure an “adequate” number of nurses were assigned to its emergency and intensive care units.

Starting in January 2022, as the omicron variant of COVID-19 surged, Roseland was frequently understaffed. Federal regulators identified five days between January and March on which the number of nurses working in the hospital’s emergency department fell below set minimums. The manager of the emergency department at the time acknowledged the staffing problems, saying they were especially “difficult.”

Alderman Anthony Beale, whose 9th Ward borders the 34th Ward that’s home to the hospital, said that on balance, the hospital is doing a “phenomenal” job. Most of its problems, Beale added, can be traced to a lack of resources.

Beale has backed recent efforts to establish a new medical district in Roseland that he said would help enhance the medical services available to residents who depend on it.

“If we had the same resources that a University of Chicago or a Northwestern or a Rush has, then we would be talking about a different type of hospital right now,” Beale said.

Carrie Austin, the 34th Ward’s alderman, did not respond to requests for comment.

While the hospital’s circumstances, including the pressures the pandemic forced on it, cannot be ignored, they do not fully explain the hospital’s recent performance, according to Dr. Robert Wachter, the chair of the Department of Medicine at the University of California, San Francisco.

“What strikes me here is that this was true for every hospital in the country,” he said. “It was true for every safety net hospital in the country. It was true for every hospital that was struggling financially, and there are hundreds of them. ... But not every hospital, even while being stressed by the pandemic, had that many citations.”

Watch the WTTW/Chicago PBS Report

When a patient showed up at Roseland’s emergency department one evening in July 2021, the events that followed at first seemed routine. The patient, who is not identified in federal records, complained of worsening abdominal pain. A doctor diagnosed them with sepsis and dangerously high blood sugar. The doctor then ordered hourly checks of their blood sugar level, and the patient was later transferred to the intensive care unit.

The next morning, the patient coded and doctors placed them on a mechanical ventilator to help them breathe. Around noon, they “coded” for a second time. A short time later, a doctor pronounced the patient dead.

A review by inspectors found that as the patient’s condition deteriorated, nurses failed to regularly check their blood sugar levels as the doctor had ordered. A Roseland official told inspectors that on the morning of the patient’s death, ICU nurses also failed to conduct a “head-to-toe” assessment, which is required by hospital protocol, to gauge how the patient was responding to treatment.

That July death was preceded by two others, with all three patients dying after periods where checks of their vital signs were inconsistent, according to federal reports.

One arrived on July 4 and was diagnosed with sepsis. Inspectors later found that the medical staff failed to consistently check their vital signs for more than 13 hours. They died just after midnight on July 6. The third patient, who had paralysis after a stroke and low blood pressure, was treated at Roseland for more than a month before their death in early July. Inspectors determined that the medical staff failed to consistently monitor their vital signs, records show.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services hit Roseland with an immediate jeopardy warning for the treatment provided to the three patients who died. It was the second the hospital received that year. Before the year was over, the agency would issue a third.

Egan and Roseland’s senior medical team tried to correct the problems cataloged by inspectors, with Egan signing off on a package of reforms. They included hiring a consultant to oversee a suite of new programs — daily audits of nursing care among them — retraining sessions on how frequently patients should be assessed, and seminars on the proper use of blood sugar meters.

That winter, Egan also hired DeVita as Roseland’s new chief quality officer. Her assignment, she said, was to focus on ensuring that patient safety protocols were followed throughout the hospital.

But before long, inspectors returned to the hospital to investigate additional deaths.

“Meaningful progress takes time,” she said.

A second wave of patient deaths came in January 2022. An ambulance brought a patient to Roseland on a frigid January evening. A doctor would later tell inspectors that, on this night, COVID-19 had stretched the hospital’s staff and resources thin, leaving patients in beds that lined along the hallways of the emergency department.

The patient had a history of diabetes and had missed several scheduled doses of medication before coming to the hospital. Paramedics noted that the effects had begun to alter their mental state and had severely elevated their heart rate, according to a federal report.

The doctor who initially examined the patient prescribed an insulin drip, then ordered them moved to Roseland’s intensive care unit. Seven hours passed before they received the medicine.

The patient continued to decline, reports show. Their blood pressure dropped, and they became unresponsive to verbal commands, nurses noted. On the afternoon of their second day at the hospital, nurses found they had no pulse. A doctor, according to the reports, pronounced them dead just after 4 p.m.

Federal inspectors made note of the delayed insulin treatment. In interviews, a nurse told the inspectors that they’d waited “a long time” for the pharmacy to prepare the insulin before the nurse finally prepared it themselves. The inspectors did not determine a reason for the delay, according to reports.

Inspectors also found gaps in the patient’s medical records where nurses had failed to document that their blood sugar levels were checked or whether a doctor was informed that their health was worsening. Nurses told the inspectors they had done the checks but acknowledged failing to document them.

Over the next two weeks, two other patients died following monitoring and assessment lapses. The hospital was cited for understaffing and for failing to ensure proper patient care. The latter would earn Roseland another immediate jeopardy warning.

The hospital, inspectors wrote, should have flagged two of those deaths for additional review. Failing to do so violated federal regulations requiring hospitals to track unusual events and unexpected patient deaths, according to the inspection reports. A hospital official, who is not named in the reports, later told inspectors that they had reviewed the cases and determined they didn’t meet the criteria for further investigation.

The official said that the hospital’s staff was under severe strain at the time, with as many as 70 patients filling the emergency department, according to inspection reports. And the hospital was not redirecting patients coming to Roseland in ambulances to other facilities to relieve the overcrowding.

“Patients,” the official said, “were being monitored as best as possible, not as they should have been.”