ProPublica is a nonprofit newsroom that investigates abuses of power. Sign up for The Weekly Dispatch, a newsletter that spotlights wrongdoing around the country.

As she sat Wednesday on the covered deck at the 4-Way Saloon in Sidell, overlooking the town grain elevator, Leslie Powell made her way down the list of tasks she had scribbled on her yellow notepad. Asking the utility company for a payment plan was first.

Powell’s husband, Mark, became owner of this busy little bar and grill in east-central Illinois just nine days before Gov. J.B. Pritzker ordered residents across the state to shelter in place in an attempt to halt the spread of the novel coronavirus outbreak.

Now, with the 4-Way closed to dine-in orders, and the couple’s savings spent on buying and fixing it up, the Powells face losing their business if they don’t receive state or federal aid. And that has reinforced a thought Powell has had before: Chicago should be separated from the rest of the state.

The idea of secession has long simmered in Illinois’ more rural and Republican counties, periodically flaring up around issues such as raising the minimum wage, the establishment of sanctuary cities for undocumented immigrants and gun ownership. And though Illinois’ secession movement — or, movements — isn’t exactly united, many who believe in the principle share a general sense of feeling underrepresented in a state dominated by Chicago’s Democratic stronghold.

The coronavirus outbreak, which has yet to touch some areas of the state, has become the most recent flashpoint, inspiring both serious promises to reintroduce secession on the ballot and Facebook memes that call for building a wall around Chicago.

Political experts say there is virtually no chance that the state will ever split, especially since it will require an act of Congress and lead to the likely election of two Republican senators to represent that new state. Still, the secession conversation is a dramatic expression of the much more widespread — and potentially dangerous — frustration with a sweeping governmental response to the pandemic that many question in areas where some homes sit acres apart and people predominantly travel by car, not public transportation.

“There’s nobody around here that’s got it,” Powell said. “We’re a farming community. We know how to wash our hands. We’re with pigs and cows and chickens. In this community, it’s really hard to comprehend.”

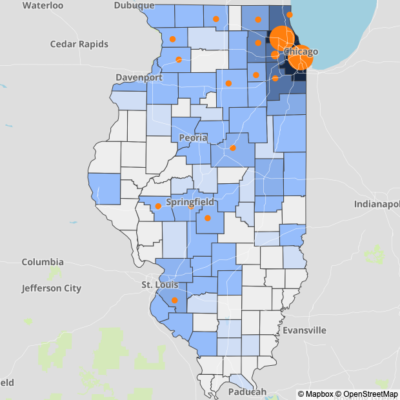

As of Thursday, 41 of Illinois’ 102 counties had yet to see a single case of COVID-19, according to the Illinois Department of Public Health. Experts caution that likely will change soon. Vermilion County, where Powell lives, reported its first two cases this week, officials there said.

On Tuesday, Pritzker announced he was extending the stay-at-home order through April. Many people said they are following it, even if their businesses and livelihoods are suffering.

At the same time, the response to the pandemic has exacerbated the feelings of some residents that the rest of the state is being forced to deal with Chicago’s problem. State Rep. Blaine Wilhour, a Republican from Effingham, said that he would like to see some regional accommodations considered to the shutdown measures, including the possibility of opening up some restaurants at half-capacity and allowing mom-and-pop stores to set up appointments.

“There’s obviously a big difference in how these broad policies affect Chicago, which is a very densely populated area, and how they affect my district,” Wilhour said.

Wilhour, along with six other Republican lawmakers, sent a letter to Pritzker last week asking for measures to help small businesses during the pandemic, including freezing the minimum wage for 18 months and implementing a sales tax holiday for the duration of the stay-at-home order.

While Wilhour said he understands the severity of COVID-19, he said the stay-at-home order has taken an enormous economic toll on his district. Residents are taking the safeguards seriously for now, he said, but they also see that the disease is not nearly as prevalent in their area as it is in Chicago.

“They see the trajectory of Illinois as not good, especially not good for people in our part of the state,” he said. “There’s a lot of pent-up anxiety about adversarial policies that are pushed down to benefit Chicago and they disproportionately don’t benefit us.”

One risk of that frustration is that people may feel less inclined to follow what they see as Chicago’s rules. Steve McNeil, who manages Rent One furniture and appliance store in West Frankfort, about 300 miles south of Chicago, said he’s concerned that some people are neither following Pritzker’s stay-at-home order nor social distancing guidelines. Though his store, part of a regional chain, remains open, he said he makes sure his staff sanitizes the store “on the hour, every hour.”

He can’t say all of his customers are taking similar steps, though.

“It’s very lackadaisical,” McNeil said. “A lot of people I don’t see taking the precautions seriously.”

McNeil said his store has seen unprecedented sales of washers, dryers, deep freezers and refrigerators — which he considers “essential items” and the reason he believes he’s allowed to stay open — and has felt heartened by the new role he sees his business providing during the crisis.

On Wednesday, McNeil’s Rent One store posted a photo on its Facebook page advertising its stock of lawn mowers: “Yard season has started and Rent One is here to help you get started. This bad boy is parked out front of the store so feel free to take a look at it TODAY!”

Rick Henson, who owns a barber shop in West Frankfort, closed Tuesday after business slowed because of the coronavirus. He now hopes to reopen next week, after he began getting calls from customers, many of whom are older people, city officials and local police officers, saying he’s a “needed commodity.”

Jared Gravatt, co-owner of Crown Brew Coffee Company in Marion, said he understands the need for the stay-at-home order but thinks the differences between Chicago and the rest of the state are “night and day.”

Gravatt said the county’s businesses are reeling from the shutdown. He and his business partner are organizing a virtual fundraising event on Friday to raise money and awareness for struggling businesses while encouraging people to abide by the stay-at-home order.

Even Gravatt, who said he recognizes the importance of protecting against the coronavirus outbreak, acknowledges the appeal of secession.

COVID-19 has “killed more businesses than it has people in this region,” he said.

Last year, State Rep. Brad Halbrook, a Republican from Shelbyville, filed legislation that urged Congress to declare Chicago the nation’s 51st state. The legislation stalled in the rules committee, where it found little support, but organizing around the issue continues. Once Pritzker’s stay-at-home order is lifted and people are able to gather again, “the interest will be as high as it’s ever been,” Halbrook said. “There’s no question about it.”

“They want to manage the entire state to suit Chicago,” Halbrook said. “They’re different lifestyles and different cultures. To do this one-size-fits-all management doesn’t work.”

John S. Jackson, a visiting professor at the Paul Simon Public Policy Institute at Southern Illinois University in Carbondale, points to similar secession movements in New York and California, where rural areas have animosity toward those states’ urban centers.

He called the perception of unequal resource distribution between Chicago and the rest of the state “a myth” that has existed for decades, and he said the stakes of that ideological divide are high during the coronavirus crisis.

“It’s a corrosive part of our culture,” Jackson said. “It has no chance at all of becoming law.”

Unlike other supporters, Collin Cliburn, a contractor and carpenter who lives outside Springfield, has led much of the state’s grassroots secession efforts. Cliburn describes his political views as “borderline old-school libertarian” and differentiates his effort from the “New Illinois” secession movement led by Halbrook as more populist and rogue than that of elected political leaders.

Cliburn hopes to collect enough local signatures to force the secession question onto statewide ballots as a referendum, county by county. So far, the strategy has paid off in Jefferson, Fayette and Effingham counties, which during the state’s March primaries voted more than 70% in a nonbinding referendum in favor of secession. While he believes, based on one-on-one conversations as well as the popularity of events he’s organized, that many in southern Illinois favor secession in practice, Cliburn said most are hesitant to vote for it.

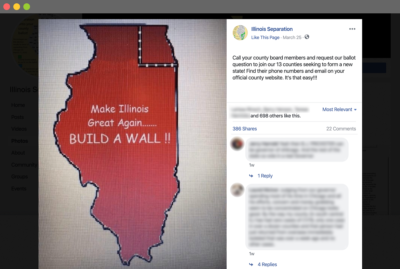

To try to build support, Cliburn has turned to social media. He makes memes, shares local news stories and writes posts across a network of Facebook groups and pages he runs to amplify differences he sees between Chicago and the rest of the state.

“What I’m doing is creating a spider web,” Cliburn said.

That spider web, which he’s crafted to function as a sort of social media ecosystem of secession sentiment, includes “Illinois Separation,” a page Cliburn runs that has garnered nearly 27,000 Facebook likes; “Illinoyed,” a page for more general venting about the state, which has about 11,700 likes; and also dozens of county-level pages for local organizers. Lately, Cliburn said, he’s been using coronavirus news to bring attention to the effort to kick Chicago out of the state.

“Everything is about Chicago,” reads a March 24 post on the “Illinois Separation” page, above a news story about Chicago preparing for a “surge in bodies” because of COVID-19 deaths. “When the Governor speaks only Chicago people stand beside him, including their Mayor Lightfoot …” he wrote. “I’m sick and tired of everything being about Chicago.”

Another post, shared on the “Illinois Separation” page on March 25, shows an image of the state of Illinois with the Chicago-area blocked off with a line. “Make Illinois Great Again … build a wall !!” the graphic reads. Comments included individuals blaming Chicago for positive COVID-19 cases in their own counties and criticizing the shelter-in-place order in areas with few if any positive cases.

The post has nearly 800 likes and 400 shares.

Pritzker spokeswoman Jordan Abudayyeh called it “appalling” that people would focus on division instead of unity during a national crisis. The governor’s duty is to every single resident in Illinois, she said.

“When COVID-19 was first reported in Illinois, it was in one county and quickly spread to more than 50 in the days since,” Abudayyeh said. “Almost every day there is a new county reporting positive cases.”

The frustration that some rural residents feel about the shutdown, or at least their expectation that COVID-19 won’t reach them, may be short-lived.

Experts warn that the low numbers of confirmed COVID-19 cases may simply reflect a lack of testing. In some counties, less than two dozen people have been tested. Because coronavirus spreads first in large urban areas then expands, it’s probably only a matter of time before the rest of the state sees cases, said Dr. Jerry Kruse, Dean and Provost of Southern Illinois University School of Medicine in Springfield

“It’s almost like throwing a pebble into a pool and watching the waves radiate out,” said Kruse, who added that it’s a “virtual inevitability” the coronavirus will reach rural Illinois.

Metro East St. Louis and Sangamon County have already started to see the number of cases rise.

“You should assume that the coronavirus has come to your county,” said Monica Dunn, assistant administrator at Edgar County Public Health Department.

Christian County, about 30 minutes southeast of Springfield, is an example of how quickly the situation can turn.

The county of 32,000 did not see its first case of COVID-19 for more than six weeks after the outbreak hit Chicago. On March 19, the county learned of its first case. For the next week, nothing changed. On March 25, there was one more.

Then overnight, 11 new confirmed cases.

“When we didn’t have any cases, there was a real complacency going on,” said Denise Larson, Christian County public health administrator. Larson said she fears the low number of confirmed cases so far in nearby counties gives a false sense of security.

The outbreak happened at a subsidized apartment complex for seniors in Taylorville after a resident attended church with someone who had contracted the disease. All 22 residents of Rolling Meadows Senior Living Apartments were tested, officials said. Two additional cases have been confirmed, bringing the total number of confirmed cases at the complex to 13 as of Tuesday.

On Wednesday, the county announced two COVID-19 deaths, a man and woman, both in their 80s.

Eighty-five-year-old Peggy Wadkins, who has lived in Christian County for more than 60 years and at the apartment complex for 10, said she spends much of her time now on the phone with her family, including her more than 30 great-grandchildren.

While residents remain in quarantine, city and county officials are checking to see if they need groceries or medicine. This week, Wadkins put her walker in the doorway so a worker could place tissues, tylenol, lunch meat and bananas on the seat without coming into contact with her.

When Wadkins looks out her bedroom window, which overlooks the now vacant parking lot, she imagines a day when all of this has passed.

Until then, she said, “No one is really safe.”