ProPublica is a nonprofit newsroom that investigates abuses of power. Sign up to receive our biggest stories as soon as they’re published.

Simon Ressner is a battalion chief with the Fire Department of New York based in central Brooklyn. Twenty-five years ago, the department, nicknamed New York’s Bravest, took on the added role and responsibility of responding to emergency medical calls. Today, firefighters make some 300,000 runs a year.

Last week, we asked Ressner, 60, to keep an informal diary of his latest 24-hour shift, a tour of duty that began at 9 a.m. on Friday, April 3.

“10-37 Code 1.”

It’s fire department shorthand for “dead on arrival.” Word of such tough calls crackles over the citywide radio in bursts.

One of my engines just returned from a 10-37 Code 1, and a firefighter is at my office door. He hands me what’s called an “alarm ticket,” and asks for a new supply of protective masks.

“Need four,” he says, as if asking for some money for candy.

I ask about the run. “She had a fever, I reached out and touched her head and she was so hot.”

I hand him four N95 masks, grab a disinfected pencil from my desk and mark on the inventory sheet: “Engine 235, Box location 431, Madison Street between Nostrand Avenue and Bedford Avenue.”

It’s around the corner from the firehouse, and so close that I can walk to my office’s rear windows and see the building. Inside, an 83-year-old woman with family nearby just died. Just outside my window.

While I’m attempting to get that to register, I hear several more 10-37 Code 1 signals come in. As I’m writing this, yet another one. The tone of the officer on the radio reporting the signal is matter-of-fact — not detached, more along the lines of, “Yep, another one.”

10-37 Code 1. Another one a minute later.

I begin my shift at 9 a.m. I grab the bleach wipe from the canister, wipe down the computer keyboard, mouse, phone, desk and 20 other places where I can imagine anyone has put their hands.

I am working as chief in Battalion 57 of the FDNY, located in Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn. Bed-Stuy is a historically African-American neighborhood that saw its population grow during the time when huge numbers of Southern blacks migrated north, leaving agriculture work for ostensibly better jobs. In the last few years, it has undergone major gentrification, but it still remains culturally and demographically an African-American neighborhood with a history of both hard times and cultural richness. Since almost all the country’s past traumas have always hit the poor neighborhoods worst, I wonder what this worst situation, COVID-19, is going to entail and for how long.

I was a fireman here 25 years ago and now have returned as chief towards the end of my career. I thought that surviving Sept. 11, 2001, would be the part of history I would tell grandchildren, but COVID has clearly surmounted even that disastrous and heartbreaking day. The department lost 343; at least 50 of them were people I knew, including my chief, Dennis Cross. He taught me how to fight fires, but also how to sail a boat, and after his death his widow gave me use of his 25-foot Catalina.

I am focused on my work of supervising the four engine companies and two ladder companies of the 57, but I also have a ritual of checking the numbers: New York City Department of Health daily statistics; the Johns Hopkins website for worldwide information on COVID cases and deaths. I quickly calculate the death percentages, taking comfort when I find the rate under 2% somewhere. But this morning the world figures show a rate of 5.23%, so I try and convince myself that it will drop because of the anomalies of Italy and Spain.

But the truth is that it is here in the U.S. where the percentages are climbing, and here in New York City where the numbers are headed toward the unfathomable. Every day I read the obituaries in The New York Times to remind myself of the pain that the families endure in a way that calculating the percentages can’t. But I am waiting. I want to see those bars in the graphs get dramatically shorter.

Yesterday, I was tasked with approving hospital and nursing home requests to use the streets around their buildings to construct tents for overflow patients. Around 11 a.m., I received the first request of several to use the streets for refrigerated trailers to store the accumulating bodies. In the moment, I can be detached enough to do the work of looking at street dimensions, trailer sizes, locations of hydrants and entrances to buildings in order to make it work. It takes me five minutes to look at that information and email back, “FDNY has no objection.” And then a few more requests for more trailers. “FDNY has no objection.”

Simple as that, we have approved the refrigerated storage on public streets of someone’s relative.

I spend a good part of Friday morning rebalancing staffing in the fire companies in the battalion as well as the 31 Battalion in Downtown Brooklyn. Staffing has become a challenge because, as of this morning, there are 1,056 firefighters, 686 EMS workers and 115 FDNY civilians suspected of COVID-19 infection; 241 Fire personnel, 74 EMS and 23 civilians have been confirmed. Fire companies that normally have 20 people on their roster are down to 11, and so we move people from companies that have fared better to those companies that are depleted. Even now, there is still a fair amount of tangled paperwork to deal with.

After, I head down to the Chief’s Vehicle and start the next disinfecting ritual. The firefighters assure me that it has been done, but they are young and I am not. And they clearly haven’t grasped the genuine risk we are facing with each contact with each other and each response for fires and emergencies.

I try to transmit a “10-18” as fast as I can when engines or trucks are responding to a fire. That signal allows me to hold one engine company and one ladder company at the scene and relieve the remaining three or four companies and get them back to their houses. I do this to limit the amount of time the firefighters hang out with each other talking, catching up, all typically done elbow to elbow. The faster I get the “18” out, the quicker I can keep them separated.

The Sirens Speak

Around noon, I watch Gov. Andrew Cuomo’s daily briefing on my computer. I haven’t yet had a fire call, but I can hear the ambulance sirens regularly. People ask how I can tell what kind of siren it is, and I realize that I have to think about that: It’s the absence of the air horns (the blasting trumpetlike sound) of our trucks and the absence of the “rumbler” that the New York Police Department uses. I definitely can tell. Another siren off in the distance — no air horn, no rumbler. It’s EMS.

When you work 24-hour shifts, it’s often easy to be confused about what day of the week it is. But with COVID, I realize that there is no rhythm for anyone anywhere. I stop myself when I ask my wife, “What’s going on this weekend?” There is no weekend, no beginning of the week. What does TGIF mean anymore?

For my wife, Moy, the load is devastating. She is an accountant for an urban planning firm, and like all her colleagues has been working from home. It is her job to get everything needed for a new PPP (Payroll Protection Plan). The faster they get the money the more likely her firm can survive. She does all this while caring for her 91-year-old mother, who lives with us and suffers from advanced dementia.

In the aftermath of 9/11, she attended every funeral from my company, six in all. And in “normal” years, she has endured all of the isolation, fear and hardship that a family member of an active-duty firefighter can deal with. I never imagined in our lifetime we would be facing what is essentially an international plague. As late as February, we still couldn’t imagine a world where the streets of New York are empty during rush hour. Or a world where — years after having to worry about infections because of damage my lungs had suffered on 9/11 — I would once again have fear that I could die of a virus! by going to work.

My nose starts itching. DON’T TOUCH YOUR FACE!!

Up until recently, the Fire Department was able to switch and swap shifts in a way that led to different people working together in a random but ordered way. But with the department’s response to COVID, we were organized into four platoons — A, B,C and D. Everyone in each group would work with the same people each time their letter came up on the calendar. The idea was that if there was a person positive for COVID in one particular group, it would only affect that particular group as opposed to infecting everyone in the company.

At the beginning of the outbreak, if someone tested positive and had been in close contact with other members, those members were directed to quarantine. Quickly that changed since the number of people testing positive was increasing rapidly. Within a week, the department revised the protocols and directed that members who were in contact with a suspected or known positive colleague should continue to work unless they exhibited symptoms. If symptoms came on, they would be placed on medical leave. During the “earlier” days of the pandemic, we all believed that you were only contagious if you had symptoms. And although we now know that is not the case, the manpower needs are such that without positive testing we continue to work until we have symptoms or if we have prolonged close contact with someone who has a positive test.

The Interim Lifesavers

The Fire Department started taking on medical calls in 1995 in order to help improve response time to serious medical emergencies by providing lifesaving care from a fire crew while awaiting transport and more advanced medical care by EMS. As a result, all firefighters are trained to provide some degree of emergency medical care, including the use of a defibrillator. But several hundred current firefighters are former EMS personnel who had transferred to the fire protection side of the department. With the number of COVID cases accelerating daily, some of those more highly trained firefighters have been brought back to supplement EMS.

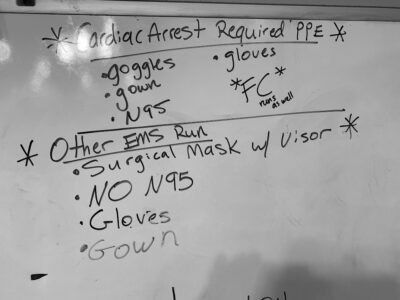

On medical runs, the firefighter’s role is to provide patient evaluation, basic life support and first aid, and if needed perform CPR until better trained help arrives. They wear protective gloves, and administer only what’s called BVM resuscitation efforts: bag, valve, mask, basically hand compressions and a device to get oxygen into lungs. Fire companies do not transport people to the hospital.

Those lifesaving protocols were shifted approximately a week ago. We always attempt to revive a patient and perform CPR, and still do. But now, our efforts are limited to 20 minutes, and so if there is no spontaneous pulse or defibrillation is unsuccessful, we cease. The exception is for what is called “obvious death,” like rigor mortis, decomposition, dismemberment.

In the afternoon, I get a phone call from Fire Operations Command Center, “How many N95 masks you have in stock, Chief? We’re doing the daily tally.” I tell him the truth — 84 — and a cheerful voice says, “Great, you’re in good shape then. Stay safe out there.”

We all say it, we all mean it, but I know that it is, as the president would say, “aspirational.” A month ago I was thinking about how to surprise my wife for our 30th anniversary. Perhaps San Francisco or London. How quaint. On April 7, my anniversary, I will return for my next 24-hour shift.

Another siren: no air horn, no rumbler. EMS. Lunch is ready.

In emergency work, if your mind, or at least your behavior, can’t adjust to what is actually happening and to deal with that as it is, you simply cannot help anyone. So the regular rhythm of 10-37 Code 1 mostly registers as a clear-eyed reminder of what is being confronted. Firefighters make this adjustment at lots of incidents: fires, car accidents, falls, construction accidents and so on. But then there is a shift back to a world that is not tragic every day or even every week.

In 2019 there were 66 people who died in fires in all of NYC — in a year! So you deal with the fire, steel your emotions, revel in the action, recognize the loss, but then there is what seems to be a respite. I’m pretty sure that by the end of my 24 hours this shift, there will be at least 66 calls that I hear on the radio for COVID-related deaths.

Isn’t there a quote about the banality of evil? The radio goes off again: ‘10-37.’

At lunch, for all my desire to isolate from everyone, I stay longer than I should have because the laughter was soothing. Five young men, with some fear but mainly strength and youth on their psychological side.

Soon, the young firefighter who had got masks from me earlier was back. “I need four.” I ask him if the patient was an elderly person. “Yes, and he was really thin,” he tells me. I say that maybe it was a cancer patient, and sure enough, he hands me the dispatch ticket and right there it says, “Patient has Cancer.”

My questions are in part meant to maintain my sense of empathy and in part to soothe my fear. I’ll be OK even though I’m over 60. I’ll be OK because I don’t have cancer.

“10-37 Code 1.” I have truly lost count. At one point, while watching Norah O’Donnell’s newscast, I hear several 10-37s. It feels like when it snows into your eyes, a little sting, a blink, a little sting.

The Daunting Curve

The message from New York State’s health commissioner plays for the 50th time. Mild mannered, even bland, he espouses the social distancing as if he’s telling young kids to share their toys in the sandbox.

Returning from a fire run, we see a double-size city bus sailing down Nostrand Avenue. There are people seated throughout, and many sitting directly next to each other. That’s one bus with 25 people who may infect 40 who then may infect 80 more. I’m a trained engineer as well as a firefighter, and my mind pictures the exponential curve from math class: mercilessly steep and ever steeper over time.

When I got to Bedford-Stuyvesant more than two decades ago, it was considered a tough and dangerous place. And it was a tough and dangerous place. Murders were through the roof. But it was a place we all wanted to be. Everyone who worked here, in fact, had to know someone in order to be assigned — “a hook,” someone who can pull a string or two.

Firefighters want to be where the action is, not because they are unfeeling or reckless but because we know that you can’t be good at this without actually doing it. Over time, dealing with fires is something that combines art, science and the deepest psychophysiology of human performance under stress. It was exciting to be here in the ‘90s, it was a great place to learn this job, but I don’t remember ever feeling this sense of looming menace. A dangerous neighborhood filled with beautiful brownstones, weary frame houses, and blocks and blocks of public housing is something your consciousness can quantify and manage. COVID is too big and too dynamic. Even 24-hour news can’t give a sense of time passing. The numbers I saw before dinner were up by several hundred by the time I walked by the apple pie and went upstairs.

This isn’t firefighting, this feels more like the crew on a sinking ship desperately trying to load the boats while the water gets ever closer.

I wish I had taken a piece of pie.

Filed under: