ProPublica is a nonprofit newsroom that investigates abuses of power. Sign up to receive our biggest stories as soon as they’re published.

This article was produced in partnership with the Anchorage Daily News, which is a member of the ProPublica Local Reporting Network.

Illustrations by Aidan Koch for ProPublica.

Dennis Mouser walked into Anchorage police headquarters on Sept. 2, 1987, for an interview he had requested with a detective.

By the time he walked out, he had admitted to sexually assaulting his stepdaughter Sherri on at least two occasions when she was 10. He’d also exposed himself to her, he told police.

It was the second time Mouser had asked police to interview him and the second time he described entering his stepdaughter’s room naked. A detective recorded his statement. Then he left the station.

A lifetime passed.

In June, Sherri Stewart, 44, looked into her iPad at the face of Karen Rhodes-Johnson, the now-retired Anchorage police detective who had investigated the case when she was a child and referred it for prosecution.

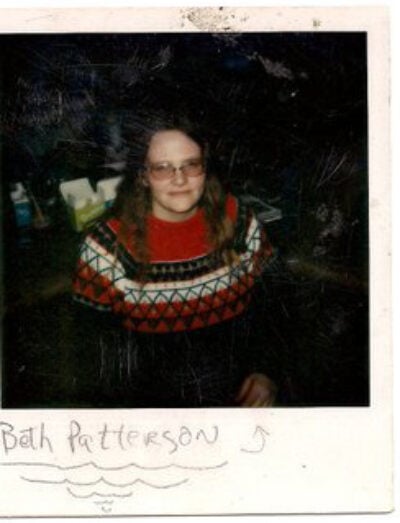

Stewart, who was born Sherri Patterson, lay in the bed that she has barely left since August 2019 because of an alarming neurological decline. Her bright red hair was in a French braid, a deep blue velvet blanket tucked around her frail body.

Nearly 34 years after they first met, this was a singular moment in the lives of a sexual abuse survivor and a detective who spent much of her career investigating crimes against children.

Why, Stewart had always wondered, had her stepfather gone free?

“I didn’t understand why he didn’t go to jail,” Stewart told Rhodes-Johnson. “And I didn’t understand why nobody was coming to take me away from all of this.”

“I’ve reread the confession,” Rhodes-Johnson said. “And yes, he did confess, twice. And I’m going to tell you that your case was one of those cases that lived with me forever because he was not convicted.”

Stewart fears her time to get answers may be running short. She told her children months ago she believes she is dying.

That was before a cardiologist visit in mid-August turned into yet another trip to the ER. It was before her husband arranged a last-minute flight to Minnesota in a desperate effort to visit the Mayo Clinic in the middle of a pandemic.

Doctors are still struggling to diagnose and treat her. Her days are urgent and uncertain.

No matter what happens, Stewart said, she wants her story told.

Stewart is among many Alaskans who still bear the wounds of childhood sexual abuse. In her lifetime, Alaska has tried and failed to reduce the soaring rates of rape and child abuse that, only now, in some corners of the state, are being recognized as epidemic.

“It can’t continue,” Stewart said. “We can’t keep breaking people and think that we are going to have a healthy society.”

In Alaska, women and girls are more likely to be raped than anywhere else in the U.S. More than half the victims of felony sex crimes in 2018 were children and teens, the vast majority of whom were abused by someone they knew, the state Department of Public Safety reported.

For Stewart, the wheels of justice turned so slowly that they undermined the few protections in place for her at the time she was a child. Her legal case made it to the state Court of Appeals in the early 1990s. Yet the long delays that prevented her stepfather from ever being held accountable or receiving treatment continue to plague sexual assault cases today. Just last year, a state judge in Fairbanks said the state’s courts were in crisis, declaring that turnover among public defenders had delayed criminal trials and denied justice to both victims and defendants.

Looking back today, some of the professionals involved in the case against Mouser maintain that they did what they could according to the laws and policies in place at the time.

Unlike many child sexual abuse cases in Alaska and around the U.S., Stewart’s was one that did receive attention from law enforcement, social services, prosecutors and judges.

Yet, amid it all, the child was lost. She told adults she was in danger, but she was sent back to endure more harm.

Stewart was 10 years old when she understood for the first time that her stepfather, Mouser, was sexually abusing her.

“It was when they first started talking about bad touches, good touches in school,” she said.

She was sitting in her classroom at Scenic Park Elementary in Anchorage when the school nurse arrived to do a presentation, she said.

Behind the school, the sawtooth peaks of the Chugach Range pierced the horizon.

Inside the lights were dim. A video played. It was unlike any class she had had before.

“It was something along the lines that nobody is supposed to touch you down there,” Stewart said. “It was talking about how people will try to scare you so you won’t talk about it. Which, of course, Dennis did all the time.”

She was grateful for the darkness as she shook and wept. As soon as she could, she ran out to the yard for recess.

“I was sitting in this big tire thing and I was crying.”

Her friends climbed in with her. “What’s wrong?”

“I can’t tell you,” she said at first.

But Stewart’s friends coaxed out her secret and convinced her to tell a teacher. School personnel in Anchorage called the Division of Family and Youth Services, or DFYS, now called the Office of Children’s Services, which reported the case to police.

That was May 1986.

The abuse began soon after Mouser joined the family, when Stewart was 4 years old, she said. “A constant, almost every night thing as a child.”

But to adults in her orbit, Stewart looked healthy and whole.

She was just a really sweet little girl, said an aunt. Bubbly and full of life, said a family friend, who remembered her love of sledding and playing outdoors.

After Stewart reported the abuse at school at age 10, the state took her out of her mother’s house in northeast Anchorage and moved her through a series of homes — family members, friends and, in one case, a foster home, Stewart said. (Foster care records are sealed, and Stewart has been too ill to file a court motion to obtain those records.)

In early June 1986, the Anchorage Police Department assigned Investigator Karen Rhodes-Johnson to the case. She had more than 15 years’ experience in law enforcement and took pride in interviewing children who had been put in terrible situations, she said.

Stewart told Rhodes-Johnson that Mouser would come into her “very own bedroom” at night, take off her panties and rub his erect penis against her vagina, Rhodes-Johnson wrote in a police report. He was always drunk, Stewart said. He would touch her genitals with his fingers. At least once, he had “used his tongue in between her legs,” Rhodes-Johnson wrote.

Shortly after Rhodes-Johnson was assigned the case, Mouser left Alaska. He spent 28 days in a drug and alcohol rehabilitation program in Washington state, he later told police. The detective couldn’t reach him.

In October 1986, about four months after Stewart reported the abuse, Rhodes-Johnson received an unexpected call from a social worker saying Mouser wanted to talk with police.

Mouser was back in Anchorage, an inpatient at Charter North Hospital. The social worker had recommended he seek psychiatric care, believing Mouser was suicidal.

In a case of sexual assault, “it is not uncommon for a suspect to reach out to detectives after learning about the investigation,” said M.J. Thim, a spokesperson for the Anchorage Police Department.

Rhodes-Johnson visited Mouser at Charter North on Oct. 15. She turned on her tape recorder just before noon. She told him he had the right to stop talking any time and the right to have an attorney present. Mouser said he understood.

The detective told Mouser that Stewart had given a statement describing sexual contact with him. She asked if sexual contact had ever taken place between Mouser and his stepdaughter.

“Uh ... I’ve tried to remember but I can’t, it’s just ... not that I can remember,” Mouser replied.

He went on to describe walking into Stewart’s room naked one time while intoxicated, sitting down next to her, and later feeling guilty about it. They were living in a trailer home in a place called Alaska Village at the time, he said, in East Anchorage.

Mouser also said he had heard from the social worker that Stewart was beginning to blame herself for being taken out of the home, but it wasn’t her fault.

“What wasn’t her fault?” Rhodes-Johnson asked in a police transcript of the interview.

“Uh, any of the ... sexual contact ... that might have taken place.”

“Did that sexual contact take place?

“Uh, like I said, I-I don’t — I can’t remember,” Mouser replied.

He said he had been struggling with cocaine and marijuana abuse and had frequent blackouts from drinking “maybe three six packs a day.” He was depressed and felt bad about not being with his wife, Beth Blake, Stewart’s mother. She was struggling emotionally, too, he said.

At a court hearing in early June of that year, Mouser said, a social worker had read an accusation from Stewart that he had “sexually penetrated her.”

He told Rhodes-Johnson he did not believe he was capable of all the acts Stewart had recounted.

But he said he felt he might have done some of them. “I-I don’t know. It’s just un ... something side [sic], deep inside ... guilt, I don’t know,” he said.

In mid-December 1986, Rhodes-Johnson sent a case report to the Anchorage District Attorney’s Office, requesting a review for charges of sexual abuse of a minor. More than six months had passed since Stewart had come forward at school and been removed from her home.

The DA’s office requested more interviews from APD, including with the school nurse, but did not immediately charge Mouser with a crime.

After a brief stay in the home of her father and stepmother, Stewart had moved in with her maternal uncle, Steve Blake, and his wife, Laura, who was a schoolteacher.

“She still was very much a little girl, and I doted on her because I didn’t have any children at the time,” Laura Blake said. She enjoyed curling and braiding Stewart’s blond hair and making sure she had everything a child could need.

During her time with her aunt and uncle, Stewart received counseling — the only time in her childhood she had mental health services, she said.

Although the Blakes had taken in a minor in need of a safe home, the child welfare system seemed distant and disinterested.

“No one communicated with us at that time,” Laura Blake said. “No court papers. No judge. No one from the legal system ever contacted us personally to talk about what was happening. We were like bystanders.”

Attorney Barbara Malchick, who supervised child advocates for 25 years in the Office of Public Advocacy, said that Stewart should have been receiving monthly visits from her social worker, and also should have been visited on occasion by her legal representative, called a guardian ad litem.

Laura Blake said that she does not remember Stewart receiving any such visits in their home or being offered any appointments other than counseling.

When Stewart was removed from her aunt and uncle’s home, her aunt thought the girl was returning to live with her mother.

“I thought she’d go back with her mom, and I thought that Dennis was out of the picture,” Laura Blake said. “And nothing turned out the way I thought it would.”

Blake said she and her husband would gladly have kept Stewart in their home had they known she was not being placed with her mother.

Instead, Stewart said, she was sent to a crowded foster home where she said she was beaten by the foster mother’s biological son. In addition to facing neglect and abuse, Stewart lost her access to counseling because of the move, she said.

A spokesperson for the Office of Children’s Services, formerly called DFYS, wrote in an email that Stewart’s files have been destroyed in accordance with policies from that time. Numerous new laws and policies have been implemented since then, he said, “including the establishment of Child Advocacy Centers designed to change the way sexual abuse allegations are investigated.”

Mouser remained free and continued his romantic relationship with Stewart’s mother. In December 1986, Mouser moved to the apartment next door. They filed for divorce, a legal split that was finalized the following March.

But Mouser later told police it was a ploy to regain custody of Stewart. Beth Blake believed that divorce was “the only way she’d get her daughter back,” Mouser told Rhodes-Johnson, that it must appear she had ended her relationship with Stewart’s alleged abuser.

In fact, Blake was pregnant with Mouser’s child at the time.

Within a month of the divorce, Stewart was sent home to live with her mother, Mouser told police.

For several months, Stewart said, she and her older brother had their mother all to themselves in a new home. It was the happiest time of her childhood, a summer of bike rides and making friends with new neighbors.

“My mom was way more stable then,” Stewart’s older brother, Donald Patterson, said. With Mouser gone, life seemed briefly normal. “There was not physical abuse, there was not mental abuse, there was not a lot of, just, negativity.”

But it didn’t last. By August 1987, Stewart’s mother was having “personal contact with Dennis on an almost daily basis,” Beth Blake wrote in an affidavit. Stewart said Mouser was, in fact, living with them.

“My mom allowed him right back into the house and then she had two kids with him,” she said.

“Dennis destroyed my mother every way he could,” Donald Patterson said. Mouser’s addictions fueled hers. “He was a blackout drunk,” Patterson said, prone to screaming and physical abuse of Blake. His abuse of Stewart was a part of the larger chaos and destruction, he said.

At age 11, Stewart was again being sexually molested by Mouser, she said. She had come forward earlier as she was taught to do, divulging a shameful secret to adults who said they would help her. But she was back in the same situation from which she had tried to escape.

“There’s nothing law enforcement could do,” Rhodes-Johnson later said. “She was back in the home because her mother was protecting the guy.”

“I could see how DFYS would get uninvolved in the case after returning the child and feeling like she was safe, and being bamboozled by the family” into thinking Mouser was gone, said Malchick, who supervised child advocates at the time.

Back then, and to this day, child welfare investigations proceeded more rapidly than criminal investigations, Malchick said, because police and prosecutors had to prove in court, beyond a reasonable doubt, that a crime had occurred.

DFYS social workers, on the other hand, could take a child out of the home quickly if they appeared to be in an abusive situation, and could return them to a parent if it was found to be safe, even before a criminal case was resolved.

Still, it was routine for social workers and the child’s legal advocate to continue visits for some months after a child returned to the home.

Stewart has no recollection of follow-up from the state. She was home, and Mouser was back.

“I went around feeling like I was not loved,” Stewart told Rhodes-Johnson when they talked this year. “At all. I just felt like I didn’t matter.”

By September 1987, Mouser was feeling anxious. A year and three months had passed since Stewart had reported him. He had no news of the investigation. He had not spoken to police about the case in nearly a year.

Two and a half months prior, in June, Rhodes-Johnson had filed a follow-up report to the district attorney detailing new interviews with Stewart’s mother, the school nurse and Stewart herself. “CASE STATUS: Pending prosecution,” she wrote.

But nothing had happened.

On Sept. 2, Mouser went in person to APD headquarters and asked about the case. Rhodes-Johnson interviewed him a second time.

She informed him that he was not under arrest and was free to stop the conversation at any point. Later, she also asked if anyone had threatened Mouser or talked him into coming to the station that day.

“I’m doing this on my own,” he said, because he was tired of “waiting and waiting and waiting.”

As he spoke, a tape recorder rolled.

Rhodes-Johnson told Mouser that there was a backlog in the district attorney’s office, and no decision about charging him had yet been made.

“The D.A. has not sat down and read the case,” the detective said. She told Mouser she had called the D.A.’s office the previous day and was told “it’s still in the pile.”

A lot had happened in the past year, Mouser told the detective.

After the divorce, Blake had moved out and got Stewart back, but Mouser remained in the building where they had lived. “We were still seeing each other,” he said, “and she was coming over to the apartment building.” Then in May, the building caught fire and burned down.

Afterward, Mouser said, he had spiraled, drinking heavily, getting into a fight. “I was a nervous wreck and living wild,” he said.

In June, he learned that Blake was pregnant with his child. “It’s made me grow up, though, this pregnancy thing,” he said.

Mouser told police that social services had been warned of his continued relationship with Blake. He said Stewart’s stepmother — her father’s wife — had called up and reported the pregnancy to a caseworker.

All this had happened “besides me waitin’ to go to jail, y’know and get it over with,” he said, referring to the pending investigation.

Malchick, the former child advocate, believes that if someone had notified the child welfare system that Mouser was in the home and Blake was pregnant with his child, it would have been required to investigate.

“I’d be very interested to know what happened there,” she said. “That sounds like a huge breakdown at that point.”

During this second interview, Rhodes-Johnson mined Mouser for more details that might be used to build a case against him. He obliged, naming specific dates on which he said he had abused Stewart, all while under the influence of alcohol and cocaine.

He also told police he had confessed the sexual abuse to drug counselors, his counselor at church, doctors and Stewart’s mother. Everyone, he said, but a lawyer, which he couldn’t afford.

In Mouser’s telling, the first time he abused his stepdaughter was Dec. 28, 1985 — three days after Stewart’s 10th birthday. He told police he had touched her vagina over her clothes. He also told her that if “it was reported in court” he’d been touching her — “teaching her about sex,” he called it — he would go to jail, and she’d be sent to a foster home. He claimed this was not a threat.

Two months later, on Mouser’s birthday, he molested her a second time. He said he forced her to touch his penis and he touched her vagina, skin-on-skin. He also forced oral sex on her. He said he thought he had rubbed his penis against Stewart’s vagina, an act she had described to police.

Then in late May 1986, Mouser said, he watched an “X-rated” video after everyone else had gone to bed.

“I went into the room … uh, naked, completely naked and she was awake and covered … scared.”

That night, he said, he talked to her but did not touch her.

“I realized what I was doing,” he told Rhodes-Johnson.

Mouser told the detective about his own experiences growing up in an abusive and dysfunctional home. How he began drinking heavily as a teen to “blank my mind to my brother’s suicide.”

Now, with a baby on the way, he appeared eager to bring the case to a close. He said he had given up cocaine and started attending the Anchorage Baptist Temple. (Stewart remembers being baptized there on the same day as Mouser, in disbelief that his sins could supposedly be washed clean.)

He also told Rhodes-Johnson that after getting out of Charter North Hospital, he had gone to Langdon, a mental health clinic, apparently seeking services related to his sexual behavior. Mouser said a practitioner there told him that the fee was too high for him to afford on unemployment, and that he would only be able to treat Mouser once he’d been arrested and taken to Hiland, the state prison.

Mouser said he made the visit to APD because he didn’t want Stewart to end up in court. “I feel it’s just — it’s a personal very personal family thing between me and her.”

Still, he believed his case was “so minor” compared with others that law enforcement dealt with.

Blake, Stewart’s mother, was outside in the car waiting for him, he told police.

Rhodes-Johnson told Mouser that she planned to call the DA’s office the next day.

She kept her word. Yet he wouldn’t be arrested for another year and a half.

In June 2020, Karen Rhodes-Johnson looked into her cellphone from the gray bench seat of her truck. She was parked in a lot in Anchorage while her husband, also a retired APD detective, ran errands in a store.

A video call with Stewart, more than 30 years after they first met, was the first time Rhodes-Johnson was seeing her as an adult. The coronavirus and Stewart’s fragile health had made it too risky to meet in person.

“Your face looks familiar,” Stewart said.

“Oh it does? A little bit older,” Rhodes-Johnson replied, adding that she hadn’t worn glasses the last time Stewart saw her.

At 73, Rhodes-Johnson wore her blond hair swept back, slender hoops in her ears. She had retired from police work more than 20 years before, after being seriously injured during a training session, she said.

Rhodes-Johnson started out in law enforcement in 1969, she said, the rare woman to become a police officer at the time. By the time she was assigned to Mouser’s case, she was working in the APD’s Crimes Against Children Unit while raising four children of her own.

The unit was often overtaxed; at one point she told a judge she worked as many as 70 cases at once.

In the mid-1980s, the department was just developing protocols for sex crimes cases involving children, Rhodes-Johnson said. She helped coordinate between agencies, she said, and sought out specialized training on working with child victims.

Now, video chatting with Stewart from her truck, Rhodes-Johnson let the child she once interviewed lead the questions.

“Well, basically, Sherri, why don’t you ask me what you’d like to know,” Rhodes-Johnson said.

“One of the biggest things was, did my mom know? Was she told?” Stewart asked.

“I wish I could say that she didn’t know, because I know that would be easier,” Rhodes-Johnson said. “But yes, your mother knew. And during my whole career, it was maybe a very, very small percentage of the children I interviewed that their mothers didn’t know.”

Rhodes-Johnson had spoken to Beth Blake shortly after Stewart reported the abuse at school and again in March 1987. Blake told her she first learned of the molestation when she was called at work by social services and told they were beginning an investigation into Mouser. Blake said she had confronted Mouser about the abuse, but he had just avoided her questions.

Their younger daughters were born in 1988 and 1989.

Starting at age 12, Stewart said she cared for her baby sisters.

During that time, Mouser and Blake abused cocaine, marijuana and alcohol. Sometimes they “partied” in the house, she said. Other times, they left Stewart in charge and drove off to visit friends.

“The abuse, then me taking care of my mom’s kids while they were doing drugs, both her and him, I felt the system failed me completely,” she said.

Patricia Phillips was a family friend in the 1980s and knew Stewart as a young child. “Her mom was obviously broken,” she said.

Blake had told Phillips that she had been raped as a teenager. “I don’t think she was capable of making a better choice for her daughter.”

As far as Stewart knew at the time, nothing had ever happened to Mouser in response to her complaint of sexual abuse.

But Mouser was, in fact, charged with a crime. The day after Rhodes-Johnson interviewed him a second time, in October 1987, she recommended to the DA’s office that the case proceed immediately.

About two weeks later, state prosecutors charged Mouser with three counts sexual abuse of a minor. A district court judge issued a summons for Mouser to appear in court.

Rhodes-Johnson said she does not know why Stewart was not again removed from her mother’s home when the summons was issued.

According to a writ filed by D.H. Daniel, a peace officer, the summons was never served. The officer wrote that Mouser’s residence had burned down and neighbors hadn’t seen him since. Around the same time, Mouser had quit his job. Daniel had no further leads.

Then on Oct. 14, 1987, a warrant was issued for Mouser’s arrest.

In a motion to supplement the record, a district attorney would later argue that Mouser was not taken into custody until much later because Alaska State Troopers were unable to find him. But he was close by all along.

On two occasions, a state trooper looked for Mouser at the home Stewart shared with her mother and stepfather. Stewart’s mother told the trooper Mouser didn’t live there.

“If the mother is protecting the guy and hiding him, and she’s a child, what could we have done?” Rhodes-Johnson said.

On the Alaska State Troopers’ second attempt to find Mouser, there was also a warrant out for Blake’s arrest, in a separate theft case. Blake was not arrested, Trooper William Hughes wrote in a report, because she was holding her newborn baby in her arms.

Those two partial days of searching, in December 1987 and April 1988, were all that troopers devoted to finding Mouser, records show.

APD’s Thim said that current practice is for detectives to attempt to serve the warrant, and for other APD officers to follow up if needed. State and federal law enforcement sometimes provide assistance. He did not comment on protocols in the 1980s.

Rhodes-Johnson later testified that after bringing the case to the DA for charges, she received no further requests. She was not asked to look for Mouser. She didn’t know what had happened to the case, she said.

Mouser continued living and working openly in Anchorage during that time. As Stewart watched over her infant sisters, he kept having contact with law enforcement and the courts, but he was not arrested.

Stewart remembers calling police in the early months of 1988, at age 12, when Blake was pregnant and nearly due to deliver Mouser’s child.

“Dennis was so intoxicated and violent he tried to strangle my mom,” she said.

“He stressed her out, yelled at her, screamed at her, beat her,” said Patterson, Sherri’s older brother. He remembers confronting Mouser that day, trying to intervene.

Stewart cowered in the kitchen area and called police to tell them Mouser was hurting her mother, she said, but Blake took the phone from her and told them that nothing was wrong.

Mouser had other contacts with police that year. Beginning in 1988, he worked at a Wash-and-Lube car wash in midtown Anchorage. He frequently washed police cruisers and had contact with officers, he later wrote in an affidavit to the court.

In April of that year, he gave a statement to police after a co-worker had stolen a car from the car wash. It included an address for him.

Then in August 1988, Blake was tried for theft. Mouser walked into the downtown courthouse and testified at her trial, again giving his name and address.

Afterward, he asked Blake’s defense attorney for information about the case against him. According to a later affidavit, the defense attorney contacted a colleague at the Office of Public Advocacy, who told Mouser his case had been “quietly shelved.”

Rhodes-Johnson said that testifying in Blake’s trial would not have triggered a check for criminal warrants.

In January 1989, Mouser was served a civil summons at the home he shared with Blake and the children, according to the same affidavit. In other words, the authorities were able to find him. But he was still not arrested for sexually abusing Stewart.

Finally, in May 1989, Mouser went to work temporarily in Whittier, an isolated harbor town outside of Anchorage. At the end of the month, he was picked up by Whittier police on an unrelated matter and arrested on the 1987 warrant. He was sent back to Anchorage and posted bail.

Three years had passed since Stewart first told authorities he had abused her.

When Stewart was 13 years old, a grand jury finally indicted her stepfather, charging him with one count of sexual abuse of a minor in the first degree and three counts in the second degree.

As an adult, Stewart has no memory of the legal proceedings; she is not sure she was aware they were taking place. Her daily life at the time involved basic survival in a home where she did not feel safe.

In August 1989, Mouser was arraigned and pleaded not guilty, and when the trial date arrived on Oct. 9, his attorney filed a motion to dismiss the indictment. The argument: The State of Alaska had taken so long to arrest and charge Mouser that it violated his constitutional rights to a speedy trial.

The three years that had elapsed since Stewart first came forward made it impossible to mount an adequate defense, he argued.

Stewart’s mother and Mouser also filed affidavits detailing Mouser’s numerous contacts with law enforcement and the courts after the warrant was issued.

Mouser said in his affidavit that he had sought out APD and given statements because he believed he needed to be arrested in order to be assigned a public defender.

For the next two days the lawyers argued on paper and in court. But not over whether Stewart had been sexually abused. The questions at hand were whether the state’s delay was reasonable, and what efforts had been made to locate Mouser.

Judge John Reese had been on the bench of the Superior Court for two months when he heard Mouser’s case. Before that, he had spent years in private practice and had been “pretty involved” in the anti-domestic violence movement in the 1970s, he said.

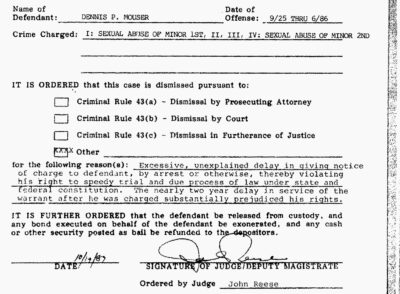

Reese found that Mouser’s right to a speedy trial had indeed been violated because of “excessive, unexplained delay” by the state. “The nearly two-year delay in service of the warrant after he was charged substantially prejudiced his rights,” the judge wrote.

He dismissed the case. No evidence was presented in court about Mouser’s guilt or innocence, including his admissions of sexual abuse to APD.

“We walked out of there in more disbelief than we could have ever done in our careers,” Rhodes-Johnson said, “not only speechless, but like somebody had punched us.”

Reese, 76, is now retired. He said he cannot comment on individual cases, nor does he remember this one in particular. But he spoke generally about questions of delay.

Speedy trial challenges are rare, he said. Prosecutors are responsible for bringing cases in a timely manner, and when they don’t, the law requires a judge to dismiss. “A judge’s discretion is really limited,” he said.

“We’re supposed to follow the law, not our whims and biases and prejudices,” he said. “Your ability to have a fair trial is greatly diminished with delay.”

Reese said it would have been improper for him to consider any evidence of a defendant’s guilt or innocence before first deciding if the case belonged in court and if the state had violated the defendant’s rights.

“Criminal law does many things,” he said, “including protecting people accused of crime.”

Rhodes-Johnson saw the case differently, although she acknowledged that the court was bound by the laws. “They abandoned Sherri’s rights,” she said. “They abandoned her rights versus his.”

The memory of that dismissal in court has stayed with her, she told Stewart in June.

“When we believe a victim, we do everything in our power. And sometimes our hands got tied. And so we had to go home to our families and hold that with us.”

The state’s case against Mouser churned through the legal system for two more years.

The district attorney appealed Reese’s decision, outlining the efforts that had been made to arrest Mouser.

Mouser’s attorney argued the state had failed in its basic duties to pursue the case.

“Throughout this case it has been Mr. Mouser who has had to come forward and prod the State along. It was Mr. Mouser who initiated both interviews with the police and who repeatedly requested that something be done with respect to this case so that it would not be forever hanging over his head,” he wrote.

“Even when the State had what amounted to two confessions, (thus characterized by this Court), it failed to prosecute this case,” he added.

The Alaska Court of Appeals decided to review the case.

While the judges worked, Stewart weathered eruptions of violence in her home.

Just two months after the judge first dismissed the case against Mouser in 1989, Stewart's mother pressed charges against him for assault. A police officer wrote that Mouser had struck Blake across the face, and the officer had seen her injuries.

Mouser was ordered not to return to the home without written permission from Blake and was sentenced to 10 days in jail, with nine suspended. But he remained in their lives.

At least twice, Blake filed for emergency protective orders against Mouser for domestic violence. In July 1990, he made a series of threats to Blake and her children:

“Threaten[ed] to kill me if I file a restraining order, threatened to throw hot coffee in my face, get my children all taken away and sent to foster homes by breaking a no contact order,” the mother wrote.

She added that Mouser “threatened + attempted to hang self in garage so we will all suffer.”

It was Stewart who found him purpled and hanging, with an electrical cord around his neck, she said. She was 14 years old. The image has stayed with her, indelible, among her childhood’s other traumas.

Mouser survived the suicide attempt and was taken to a psychiatric hospital, Stewart said. His relationship with Blake fell apart. By October 1990, she filed for custody of their two daughters.

A few months later, in February 1991, the Court of Appeals issued its opinion in the case against Stewart’s stepfather.

Chief Judge Alexander Bryner wrote that the state’s efforts to arrest Mouser on the warrant appeared “patently inadequate when viewed in isolation,” but that prior attempts to serve him with a summons made it “less flagrant.” Still, the court agreed that the 20-month delay in arresting Mouser was unreasonable.

Ultimately, the result was the same.

The Court of Appeals asked for a different legal test to be applied to the question of Mouser’s right to a speedy trial. They sent the case back to the trial court.

Again, Reese presided. He applied the new legal test but still found that the state had failed in its basic due diligence. “One can only conclude that the government did not care about trying to serve the warrant,” he wrote.

It was the state’s job to gather the evidence against Mouser and bring him to court. It had taken far too long.

On Dec. 23, 1991, Reese dismissed the criminal indictment against Mouser for the final time. Mouser was free to go.

A representative for the Alaska Department of Law said that none of the district attorneys involved in the case still work for the department. “We no longer have the 30-year old files pursuant to our file retention policy. Without first-hand knowledge to answer your questions about the handling of cases 30 years ago we are unable to answer your questions,” she wrote.

Stewart turned 16 two days after the final court dismissal. Six and half years had passed since the day she had crawled into the tire in the school yard and cried.

A month or so before the final dismissal, Stewart’s mother had moved the family to Washington state. Distraught to be leaving Alaska, Stewart was determined to forge her own path.

She moved out of her mother’s house as a teen, she said, the beginning of many years of wandering across the country and back up to Alaska.

When Stewart was 20, she said, her mother was hospitalized with liver complications from hepatitis C. She died the following year in West Virginia, still denying to Stewart that she knew about the sexual abuse.

Mouser’s later years can be traced in a series of entries in CourtView, Alaska’s database of court cases. Entering his name results in a list of charges for driving while intoxicated, shoplifting, public drunkenness.

And domestic violence. In addition to Blake, two more women filed complaints against him in the following years.

Mouser died in 2009. Stewart only found out in 2017.

Stewart’s adulthood led her all over the country. She joined the Navy at 23 and was raped shortly thereafter, she said. This time she didn’t report it, fearing retaliation. Years later, Department of Veterans Affairs doctors diagnosed her with PTSD.

In 2017, Stewart moved back to Anchorage after many years in the Lower 48. Her family photos are bound in leatherette albums and stuffed in popcorn tins that her grandmother passed down to her. She keeps them in her bedroom now at her home in Hillside, hoping little by little to organize them and excavate her past.

The pictures capture holidays and birthdays, smiling faces and dated haircuts. But for Stewart, each one is cast over with darker memories. There’s the Christmas tree her stepfather was too drunk to mount in a stand. The outfit she wore in elementary school that he told her was too provocative. The house where he beat and choked her pregnant mother.

“I can’t stand it,” she said, having those photos so close and seeing herself with her abuser.

But the albums also hold her childhood protectors, the adults in the family — her grandparents, her aunt and uncle — who offered moments of safety and reprieve.

In Anchorage, over the course of two years, Stewart attended college classes in human services and psychology, she said, which helped her cope with her past trauma.

“I realized that I, as a child, did what I was supposed to do, and my mother failed me. The system failed me. It wasn’t me. And that’s a really, really hard thing for victims, especially childhood victims, to understand.”

Stewart said her studies in psychology also allow her to feel empathy for Mouser, even though she wished he had been held accountable for the abuse. She dreamed of a career helping people convicted of sex crimes get mental health care.

“Sometimes the people who sexually offend are actually really mentally ill and they need mental help, not just being put in a prison where they’ll become a more violent offender,” she said.

But that dream and all her others have run up against the limits of her faltering health. It has been a mysterious and devastating transformation over the course of a year.

A photo from last July shows Stewart immersed in the turquoise water of the Bahamas, head tilted back toward the sun, wet hair draped over her shoulders. Her husband, Alain, laughs beside her.

This June she posted photos of an IV in her arm, the surgical mask protecting her, her red hair spread across a clinic pillow.

For much of the past year, Stewart has moved with the aid of a wheelchair or walker, when she can move at all. She faints often, due to sudden drops in blood pressure. She has trouble swallowing, muscle atrophy, numbness in her leg and lost more than 50 pounds in recent months, she said. Her voice often dims to a whisper.

“We are frankly terrified,” Alain Stewart wrote in a note to a VA doctor in June.

Finally in August, a specialist in Anchorage told Stewart she may have a rare and incurable connective tissue disorder, as well as a condition related to her low blood pressure and fluctuating heart rate.

When she returned about two weeks later for test results, he sent her straight to the emergency room. Within days, she lost the ability to verbalize her thoughts, trapped in the maze of her own mind, she said.

Fearing the worst, the Stewarts decided to risk a flight to Minnesota, hoping the Mayo Clinic could save her life. Doctors there described a functional neurologic disorder: the structure of her brain was not damaged, but the wiring wasn’t working right.

Staff worked with her to practice words and syllables until she regained the ability to speak over the course of several days. The first sentence they gave her to repeat was, “Today is a sunny day.”

As she improved, the sentence she chose to practice was, “I was given this life because I’m strong enough to live it.”

Stewart has now returned to Anchorage to wait for a longer-term spot at the Mayo Clinic and a more definitive diagnosis. She is scheduled for further evaluation and treatment at its Scottsdale, Arizona, campus beginning in mid-October.

Rhodes-Johnson remains steadfast in her belief that she did all she could for Stewart all those years ago.

In other cases she won convictions, she said. She worked on thousands over her career. She couldn’t let the losses hold her back, she said. The work ahead was too important.

For Stewart, a video call during the pandemic marked the first time she could get answers from an adult who remembered her at the time the case unfolded, who had worked in the system that had let her down.

On the one hand, Stewart wants to expose how she was denied justice. “I want people to know how bad the system failed me as a person. I could have had a better life.”

On the other, she offers her story as proof positive that survivors can “rise above the poverty, the drugs and the abuse.”

“It’s not your whole life,” she said. “That’s the past. What you do afterwards is who you are.”

For Rhodes-Johnson, their encounter was a chance to try to help a former child victim heal an old wound. Stewart was one of myriad child victims she worked with who never saw justice, she said.

“I’m hoping that you’ll see me not as a horrible part of your past, but someone who really did care to make sure that didn’t happen.”

She offered words of encouragement — “I’m proud to see that you made the best of this” — and the hope that other victims, as adults, might get the same chance as Stewart.

“I can see now that victims need to, if they feel that this helps them to get through this, meet with the officer that you’ve dealt with, meet with a social worker, find out later what went on,” Rhodes-Johnson said.

A lifetime after Stewart turned in her stepfather and was abandoned to his abuses, four words cut across the years.

“Sherri, I believed you.”

Adriana Gallardo contributed reporting.

Stewart first contacted ProPublica and the Anchorage Daily News via our online questionnaire about sexual violence in Alaska.

Have You Experienced Sexual Abuse or Sexual Violence in Alaska?

We’d like to hear your story.