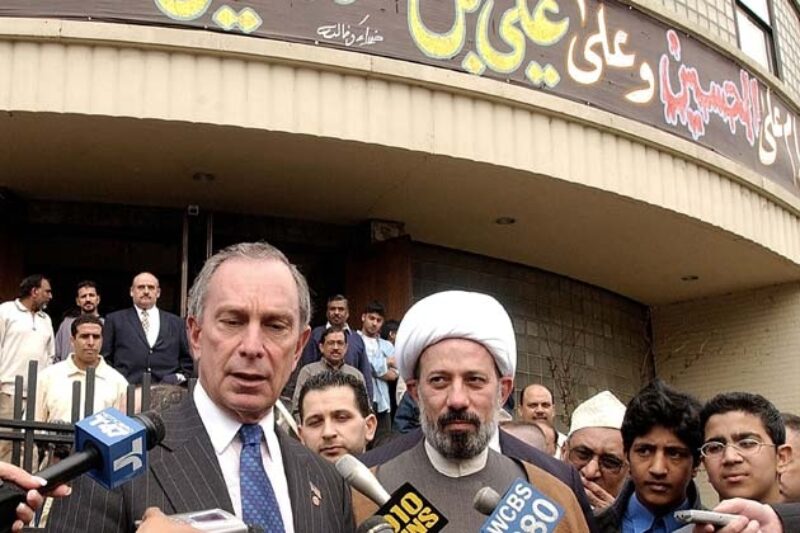

In July 2004, New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg presided over a celebratory signing ceremony at City Hall for a new law that banned the NYPD from racial or religious profiling. Advocates gushed. The mayor hailed the new law.

“Racial profiling will not be tolerated in our city,” Bloomberg declared after reading the law’s definition of racial profiling, which includes religion. “New York City is home to 8 million people of every race, ethnicity and religion from all over the world.”

Fast-forward to the present, and the NYPD has come under fire for spying on the Muslim community in the city and beyond, including using informants to prepare reports on political speech at mosques and dispatching undercover officers to map Muslim-owned businesses in Newark, N.J.

The activities seem to counter at least the spirit of the law. So, why hasn’t there been an investigation or enforcement?

The answer may lie in the text of the law itself, which experts say is vaguely worded and lacks a clear enforcement mechanism. Further, there appears to be little political will among city and state officials and prosecutors to go after the NYPD over profiling.

"The racial profiling law, to me, does not appear to be worth the paper it’s written on,” says Eugene O’Donnell, a former NYPD officer and prosecutor who is now a professor of police studies at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice at the City University of New York.

O’Donnell and others point to the section of the law defining profiling. Here it is:

an act of a member of the force of the police department or other law enforcement officer that relies on race, ethnicity, religion or national origin as the determinative factor in initiating law enforcement action against an individual, rather than an individual's behavior or other information or circumstances that links a person or persons of a particular race, ethnicity, religion or national origin to suspected unlawful activity.

Those two bold-face phrases are at the heart of the matter. The law does not define either phrase. "The word 'determinative' – what does that actually mean?" asks O’Donnell.

"The devil is in the details, and it all boils down to how we define profiling,” says Udi Ofer, advocacy director at the New York Civil Liberties Union. “Right now, the definition is very weak. "

That may be by design. The original version of the bill drafted by the city council defined racial profiling somewhat differently — it focused on the NYPD’s practice of “stop and frisk," and it outlined specific penalties. Officers could have their leave reduced, be ordered to do community service, and be suspended or fired for violating the law. But the final version was watered down, reportedly following objections by Police Commissioner Ray Kelly. The measure was “reduced from a toughly worded proposal several pages long to a single paragraph,” the Associated Press noted at the time.

"Unless there's an explicit enforcement provision, it's difficult to enforce laws," Ofer says. On Wednesday, City Councilman Jumaane Williams introduced a tougher anti-profiling bill, which outlines how victims of profiling can sue the city.

The city and state officials who might investigate have so far declined to do so or aren’t commenting.

New York Attorney General Eric Schneiderman last week said he would not to look into the NYPD's surveillance of Muslims, citing "significant legal and investigative obstacles." Asked by ProPublica about potential violations of the 2004 law, the office of New York County District Attorney Cyrus Vance declined to comment. The office of Public Advocate Bill de Blasio, which plays a watchdog role for city residents, also declined to comment on the surveillance of Muslims by the NYPD.

U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder did say this week that the Justice Department is beginning to review whether to investigate possible civil rights violations by the NYPD.

The 2004 anti-profiling law has apparently not yet come up in court, so there is no precedent that might offer clarity on its phrasing. "The 2004 law, as far I know, has never been used in terms of someone claiming in court that it's been violated," Ofer says.

As we noted earlier this week, the NYPD’s activity also raises questions about potential constitutional violations and other rules that govern police investigations.

Bloomberg’s office and the NYPD did not respond to requests for comment. The mayor recently maintained that the NYPD’s surveillance of Muslims is “legal” and “constitutional,” though he has not repeated his earlier claim that the NYPD merely follows threats and leads, and does not consider religion.