ProPublica is a nonprofit newsroom that investigates abuses of power. Sign up to receive our biggest stories as soon as they’re published.

ProPublica is working with THE CITY, WNYC/Gothamist and The Marshall Project to report on how allegations of misconduct by law enforcement officers in New York are investigated and to examine and analyze police disciplinary records that have recently been made public.

This story includes reporting and analysis done by THE CITY.

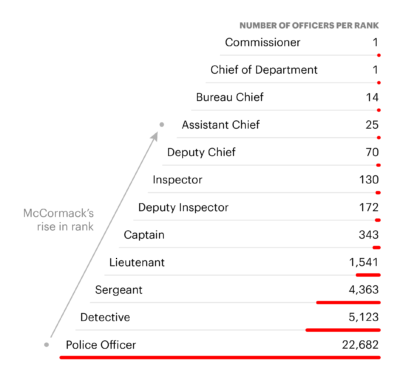

Christopher McCormack is one of the New York Police Department’s highest-ranking officers. As an assistant chief, he helps oversee drug enforcement and organized crime investigations throughout the city. He was hand-picked for the promotion two years ago by his old friend James O’Neill, who was police commissioner.

But his ascension started three decades earlier, when he was a rookie cop patrolling drug-infested Washington Heights. “He was always the first guy out of the car,” said Joseph Esposito, his precinct commander at the time. “Always the tip of the spear.” He would earn the nickname “Red Rage” for his ginger hair, fiery temperament and aggressive approach to policing.

Street cop. Sergeant. Lieutenant. By 2006, McCormack was running his own narcotics squad. Captain. Deputy Inspector. By 2011, he had his own precinct, more than 200 officers in his command. His rise continued, said a former colleague, like “greased lightning.”

Along the way, police leaders were privy to an ever-growing list of complaints against McCormack, signs that his harsh tactics and heated temperament were pushing the limits. Some of the grievances were made in lawsuits that the city eventually settled. Others were submitted to the Civilian Complaint Review Board, created to investigate misconduct. Many of the allegations were hidden from public view.

Using court records, newly released data and a trove of confidential documents, ProPublica has pieced together just how much top officials had to look past to promote him.

The allegations against McCormack read in some ways like those against many other cops in the NYPD: that he was destructive in searching a home or overly physical with someone on the street. What stands out, though, is how often Black and Latino men accused him of invasive, humiliating searches. They say he pulled down their pants in public, exposing their genitals; some said he used his fingers to search for drugs around and inside their anal cavities or directed his officers to do so.

All told, ProPublica found that at least 15 men spoke to this pattern of behavior.

One man claimed he was “told to get on all fours while naked” before he was probed with a finger. Another said McCormack searched him so violently, pulling crack cocaine from his anal cavity, that he felt he needed to go to the hospital. Then there was Unique Kennedy, who said that when McCormack dug around in his underwear, “it felt like someone getting sexually abused, assaulted.”

McCormack is just one of dozens of high-ranking NYPD officers who have risen despite allegations of misconduct in their records.

Eighty-six of the roughly 420 officers in the department who currently hold a rank above captain — running precincts and other large commands and overseeing hundreds of officers — have tallied at least one misconduct allegation that was substantiated by the CCRB, meaning that investigators amassed enough evidence of offenses, ranging from bad language to pistol whippings, to say that they happened and broke patrol guidelines. The most common involved improper property entries and searches.

For many of the officers, their substantiated complaints are dwarfed by a far larger list of those that are “unsubstantiated,” meaning investigators could not reach a conclusion on what had happened. Sometimes, complainants have no witnesses to support their claim. Other times, the NYPD fails to hand over key evidence.

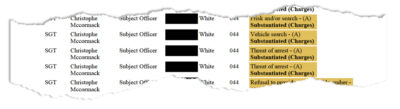

Of at least 77 allegations made against him in 26 separate CCRB complaints, 29 were unsubstantiated; five were “unfounded,” meaning investigators concluded the incident never took place; and 27 were “exonerated,” meaning the conduct fell within patrol guidelines. Investigators have never proved that McCormack strip-searched men in the street, let alone penetrated them with his finger, though the city settled four lawsuits involving strip-search allegations against him for a total $184,500.

In all, the CCRB substantiated 16 allegations lodged in six complaints, most involving the stops and searches of young men of color. No other high-ranking NYPD officer has amassed as many substantiated CCRB complaints.

Promoted Up the Ranks

Over three decades, Christopher McCormack rose to an elite tier of the New York Police Department numbering only 25 officers. Promotions beyond the rank of captain are primarily at the discretion of the police commissioner.

To understand why and how officers can be promoted despite such records, ProPublica spoke with dozens of people who crossed McCormack’s path, from colleagues who admire him to Black men who say he violated them to CCRB investigators who parsed through complaints about him and officers like him. We obtained confidential investigative files to understand how the CCRB examined allegations against him.

When we reached McCormack, he referred us to the Police Department, which did not answer questions about his record or the extent to which it had independently investigated the citizen complaints before promoting him. Documents obtained by ProPublica show that at least one strip-search allegation was referred to the NYPD’s Internal Affairs Bureau, which then sent it to NYPD leadership; it's unclear what happened afterward.

The NYPD said that it continuously evaluates the conduct of its officers “through a host of internal monitors” and factors in their CCRB histories and lawsuits, along with their “record of fighting crime,” before promoting them.

But more than a dozen current and former officers say there is no formal system for examining CCRB complaints as part of the promotions process, and there should be, especially if an officer’s record suggests a pattern of troubling conduct.

As for McCormack’s record, officers offered various defenses: that aggressive searches can be necessary to find drugs or stay safe; that he often stopped people of color because he worked in Black and Latino neighborhoods; that he was “hands-on” at a rank when most officers step back; that criminals may have made false complaints; even that his red hair may have caused people to identify him more than other officers.

Esposito, who went on to become the department’s highest ranking uniformed officer, noted McCormack’s long tenure in narcotics, an intense beat involving many encounters. “He made a lot of arrests. Twenty-six complaints? That’s less than one a year, six times where something was substantiated by the CCRB. Are you kidding me? This is just part of his job.”

But many of the officers also said that it’s possible to be an effective cop without so many complaints. An overwhelming majority of the city’s 36,000 officers do not have a single substantiated complaint on their records; only 1 in 9 does.

Alex Vitale, a critic of the NYPD who has advised the federal government on police accountability, said McCormack’s record was troubling.

“In any normally functioning system, this would be considered a huge red flag and something would have to be done about it,” he said. “If there is a pattern of even unsubstantiated complaints, this should be considered a warning sign.”

In 1989, New York City was besieged by violence, awash in drugs.

If crime were a fire, it burned hottest in the 34th Precinct in Washington Heights. Sandwiched between the Hudson and Harlem rivers along the northern reaches of Manhattan, its geography made it perfect for peddlers of crack and heroin; the George Washington Bridge brought in customers from New Jersey; I-95 gave access to the Bronx. Its tenement buildings made for invaluable gang turf, and shootouts for control were nonstop. At a time when each year brought another record murder tally, more people were killed in the 3-4 than almost anywhere else.

McCormack, who joined the force that July, seemed made for the moment. Those who aspired to become detectives needed arrests, said a former detective who worked with him. “Riding around in a livery cab, pulling people over, chasing people. … You had to have a certain level of bravado to put yourself in harm’s way like that.”

McCormack had it, and in the ensuing years, he would benefit from a novel way in which the NYPD would measure and respond to crime.

In 1994, new Commissioner William Bratton instituted a management system called CompStat. Instead of just responding to 911 calls, the department would vastly expand its use of data, seeking to pinpoint, even predict, hot spots and deploy officers accordingly. Inspired by the “Broken Windows” theory in criminology, the NYPD began directing intense attention to the most minor infractions, believing this would improve public safety and reduce crime overall.

Every person McCormack stopped became a data point; the guns he recovered, the baggies of cocaine he pulled, all tallied like points on a scoreboard by a department that valued statistics more than ever.

For men who lived in high-crime neighborhoods, always communities of color, the dragnet descended and never let up. Even as crime began to decline, ultimately falling to some of the lowest levels in the city’s modern history, many of those neighborhoods endured an exponential surge in the practice of stopping and questioning people deemed suspicious.

Over the years, a profound consequence of the NYPD’s expansion of stop-and-frisk became clear. Most of those stopped were young and Black; almost all had been acting lawfully, walking away without an arrest or summons.

In 2013, a federal judge ruled that the way the NYPD had carried out stop-and-frisk violated the constitutional rights of people of color. It cast such a cloud over the legacy of former Mayor Michael Bloomberg that during his presidential run last year, he apologized, acknowledging that it had led to an “erosion of trust.” The city has since tried to distance itself from it.

Many of the more than 12,000 CCRB complaints examined by ProPublica stem from broken windows offenses and stop-and-frisk policing.

ProPublica obtained them this summer through a public records request after New York repealed a controversial state law that had kept them secret for decades. But soon after, the unions persuaded a federal judge to block further releases of records that were not substantiated. The lawsuit is ongoing. In response to questions about the records, the NYPD said it is waiting for the conclusion of the lawsuit to comment in detail. “While we remain committed to increased transparency, we are equally committed to due process.”

The complaints reflect a level of aggression incentivized by top police officials, said Darius Charney, an attorney with the Center for Constitutional Rights who helped lead the federal case against stop-and-frisk. Cops that are “out there arresting a lot of people, ticketing a lot of people, harassing a lot of people, that’s the kind of police activity that these departments around the country reward.”

There is a stubborn belief that exists within the department that large numbers of complaints are just proof that a cop is doing the job right, and cops without them aren’t aggressive enough, former officers and CCRB investigators said.

In her nearly three years as a CCRB investigator, Krista Kano said she saw “more and more cases that I had substantiated and I didn’t feel like the consequences mattered or were a deterrent for that behavior.”

Maurice Phillips is still fuming over what he said McCormack did to him on the afternoon of Jan. 22, 2003.

“Harassing, harassing,” Phillips said in a recent interview. “It wasn’t cool.”

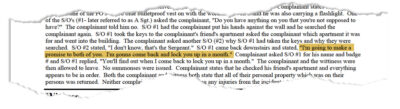

The way he tells it, he and his friend Carlos Ortiz were standing outside of a housing project in the South Bronx when McCormack pulled up in a police van, stopped them and began searching through their pockets. McCormack took the keys of both Phillips and Ortiz, used them to enter their building, then came back out and threatened them both.

“I’m going to make a promise to both of you,” Phillips later recalled McCormack saying. “I’m gonna come back and lock you up in a month.”

Phillips also told the CCRB that one of the officers told him to get used to being questioned, “that this is what is going on now in his neighborhood,” investigators wrote. Another officer allegedly told him that he was lucky because they were searching some people every day.

The CCRB received Phillips’ complaint on Jan. 27. Four days later, Phillips was at the same intersection waiting for his friend Leon Miller. He was getting ready to help Miller paint his home in New Jersey when he said McCormack returned with two other officers. This time, in addition to taking Phillips’ keys again, McCormack also found Miller’s keys and searched his car.

When Miller asked McCormack why he was searching his car, he told investigators McCormack replied: “I’m a sergeant. I can do what I want.”

Again, McCormack did not find anything on them and did not arrest them.

In a recent interview, Miller, who has worked for 20 years at the New York City Department of Education as a heating, ventilation and air conditioning technician, said he felt like he was targeted because of his race, hair and car. He said he was driving a Lincoln Navigator and wore his hair in cornrows at the time McCormack searched him.

“It just feels messed up,” he said. “It’s like you just can’t do what you want to do when you’re Black. Like even if you are doing right, they look at things to find out … to make it so you are doing something wrong.”

He decided to complain, too.

Multiple entities are responsible for investigating abuse and corruption by NYPD officers. The department has internal investigators, and state and federal prosecutors can bring criminal charges. But it’s the CCRB that’s supposed to provide an independent venue for citizen complaints. Established 70 years ago to address “police misconduct in their relations with Puerto Ricans and Negros specifically,” it has the authority to investigate everything from discourtesy to excessive force.

When McCormack sat before CCRB investigators to respond to the complaint from Phillips and Miller, he evinced pride that he was well known in the area he patrolled.

“I talk to the whole corner so, uh, they all know me. I always break their chops and stuff like that … in a good way,” he said. “They all call me ‘Sgt. McCormack,’ he’s no joke. They all know when I show up, they gotta leave.”

He said he did not recognize the names of the men, but when shown photos of two of them, he said they were familiar faces on the corner and he may have arrested or written a summons to one before. He told the investigator he only took people’s keys when they agreed to hand them over, and he said he sometimes did this so he could verify that people he stopped were living where they said they lived.

McCormack said he patrolled their corner often because it was known for drug sales. When asked specifically whom he had seen selling drugs, McCormack said “the people we constantly lock up.”

According to the investigation, he said he had no documentation from the day’s events because “any stops he made at this location led to arrests and therefore, Stop-and-Frisk Reports were not required.” McCormack said he didn't recall stopping the men and he denied taking anyone's keys.

The CCRB noted that the testimony of each complainant lined up and that it found Miller’s particularly credible. “Mr. Miller is a homeowner in New Jersey and works two janitorial jobs for schools in the Bronx,” the investigators wrote. “Mr. Miller would seem to have little motive to fabricate or exaggerate allegations.”

The investigator substantiated all 10 allegations of “abuse of authority,” including improper searches, threats of arrest and McCormack’s refusal to provide his badge number. The investigator noted that in one of the allegations, neither McCormack nor his fellow officer could “provide any documentation or testimony to demonstrate that they are conducting these investigations in accord with procedural guidelines.”

The CCRB recommended discipline. But it was up to the police commissioner to punish McCormack.

The NYPD has long chafed at robust civilian oversight, whether from mayors, prosecutors or the CCRB, and police unions have repeatedly sought to limit the agency’s legal authority and political standing. Officers interviewed for this story described the CCRB as inept or ineffectual, saying that the agency is biased against the police and that its staff lacks the investigatory experience to credibly examine allegations of misconduct.

The CCRB countered that its investigators are rigorously trained and every recommendation is reviewed by experienced professionals, “ensuring that investigations are thorough, complete and fair.” It’s the police who slow-walk and sometimes all-out obstruct their investigations, CCRB staffers have told ProPublica.

Even when the CCRB substantiates a complaint, the police commissioner can veto or downgrade the proposed discipline. Court records show the department has historically rejected substantiated complaints that hinge on the credibility of a witness. And the NYPD has increasingly disagreed with CCRB’s substantiated findings in complaints about stops, frisks, searches and trespasses.

At the time of Miller and Phillips’ complaint, substantiated allegations sometimes went to an administrative trial where the judge was an NYPD employee, the officer could be represented by union lawyers and the cases were prosecuted by an NYPD lawyer.

“Nobody goes through CCRB and says, ‘Hey listen, I’m going to really find my justice here,’” said Marq Claxton, a former NYPD detective and spokesman for the Black Law Enforcement Alliance, which represents Black police officers who advocate for civil rights. “You go through all these machinations … and jump all the hurdles … and finally make it to a point where you get a founded complaint against a police officer and ultimately the penalty will be decided by the police commissioner.”

Records show that Phillips complained about McCormack again, just before he was scheduled to testify against him in the administrative trial. He said that he encountered McCormack and another officer at a restaurant on Mt. Eden Avenue. The fellow officer asked, “Is this the guy?” And the two began taking photos of Phillips with their cellphones. Officers denied that their phones were equipped with cameras, and Phillips could not be reached by investigators.

McCormack was later found not guilty of the substantiated allegations. He was never punished.

Miller was disappointed, but not surprised. “The system is not working, especially in the Black community,” he said. “It’s not for us.”

Claxton echoed Miller.

“It’s a broken system,” he said. “It’s a system that was not intended to work effectively and it’s doing exactly what it was put there to do. And that’s to give cover to the Police Department, to give the illusion or the impression that they have some semblance of independence in investigating these police misconduct cases. But the reality of the situation is that it’s not independent at all.”

In June, the New York City Council passed a reform package that required the NYPD to improve and make transparent its disciplinary system. Last week, the department released a draft of its “disciplinary matrix,” which, among other changes, could impose stiffer penalties for supervisors who commit misconduct, but ultimately those penalties will still ultimately be decided by the commissioner. NYPD is collecting public comments on the proposal.

Documents show the allegations against McCormack grew, but the outcomes remained largely the same as he continued to advance. In two years, he went from lieutenant to captain to commanding officer.

By September 2011, McCormack was deputy inspector and commanding officer of the 40th Precinct in Mott Haven. He would supervise roughly 235 officers patrolling an area of the Bronx that remained stubbornly violent, even as crime fell almost everywhere else.

“I spent 38 years of my life in the Bronx,” he later said at a court hearing, referring to his upbringing on the other side of the borough, in the Throgs Neck neighborhood. “I was very excited about going back.” Community leaders and police officers helped him identify a cluster of public housing six blocks north of the Major Deegan Expressway from which violence appeared to emanate.

McCormack impressed police executives. He took part in federal prosecutions of gangs in the area, and in rapid-fire CompStat sessions at Police Headquarters, he could deftly explain upticks in crime or enforcement.

“It’s a numbers game,” said Edward Carrasco, a lawyer and retired NYPD deputy inspector, voicing an opinion about metrics held by many in the department. “In the simplest form, CompStat is: ‘Hey, you know, you wrote 100 summons last year, this year, you have to write 101. And next year, you have to write 102.’ … So when that’s how the game is played, the more aggressive you are, the better — and I’m using my air quotes here — the ‘better’ supervisor you are.”

To make arrests, McCormack expected officers in his command to make use of their stop-and-frisk authority. Stops tripled in the 40th Precinct for the first six months of his tenure, according to police data. To help understand McCormack’s effect on crime, ProPublica analyzed data that experts consider a bellwether for a violent precinct like the 4-0: murders, rapes and robberies. In the roughly two years that McCormack led the precinct, murders fell, rapes remained about the same and robberies increased.

Two officers who worked with McCormack in that time, Pedro Serrano and Ritchie Baez, said he took stop-and-frisk too far. “We were taught to strip-search every arrest, which is insane,” Serrano said. “He would say if your finger doesn’t smell like shit afterwards, you didn’t do it correctly,” Baez said.

They said he was known as the “credit card swiper” or “credit card Chris,” because of the way he would move his hands through the buttocks of people he was searching. Serrano said he saw McCormack push his hands into men’s underwear on multiple occasions and he would often wonder if the searches were legal.

The NYPD Patrol Guide states, in all uppercase letters, that “UNDER NO CONDITIONS SHALL A BODY CAVITY SEARCH BE CONDUCTED BY ANY MEMBER OF THE SERVICE.” An officer must also have a search warrant to perform a cavity search, and any object found can only be taken out by a medical professional.

At least three men have accused McCormack of performing or supervising cavity searches, including one who said he and another officer brought him to a holding cell, pinned him down and pulled a bag of crack cocaine out of his anus. McCormack, along with the officer, denied the allegation, saying a palm-sized quantity of drugs were in the man’s underwear. It was the man’s word against that of the officers and the CCRB could neither prove nor disprove it.

The patrol guide also mandates that strip-searches are only to be done in the “utmost privacy.” “They’re never to be done in public,” said Brooklyn Defender Services lawyer Maryanne Kaishian. “They’re never to be done to humiliate somebody.”

According to lawsuits and CCRB documents, McCormack is alleged to have conducted public, aggressive searches of men’s genitals on at least six occasions.

Paul Butler, professor at Georgetown University Law Center and author of “Chokehold: Policing Black Men,” said he saw in the McCormack complaints an effort to dominate and publicly humiliate Black men, part of a legacy of mistreatment by law enforcement and citizen mobs dating back to Reconstruction.

“It’s about power,” said Butler, who specialized in prosecuting public corruption when he worked for the Justice Department. “It’s about the police demonstrating their dominance of the streets.”

Serrano said he once saw McCormack pull down a man’s underwear on a sidewalk, exposing his genitals, to conduct a search. The man shivered because he said McCormack’s hands were so cold on the man’s testicles, Serrano recounted. He said he found it especially strange that McCormack was doing this as a deputy inspector, when most commanding officers began to spend more time behind a desk.

Wilbur Chapman is a former deputy commissioner of the NYPD who was once in charge of training. He and other officers said the allegations raise questions about McCormack’s judgment. “I don’t care who you are, if you’re a deputy inspector, there is absolutely no reason for you to strip-search anybody for any reason,” Chapman said. He and several other officers said a subordinate should do so under supervision.

ProPublica spoke with two people who say they were searched this way after McCormack was made a deputy inspector.

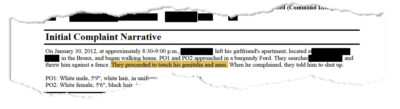

On Dec. 31, 2011, Unique Kennedy said he was getting ready to celebrate the New Year. He was leaving a liquor store with friends when McCormack and another officer rolled up to them in a squad car.Kennedy said McCormack pinned him against the wall and dug into his underwear with his free hand.

“Is this legal?” said Kennedy, remembering his thinking. “There are other officers watching and no one can stand up and tell him to stop? I felt violated.”

According to his CCRB complaint, Kennedy was charged with possession of a controlled substance. He said the charges were related to outstanding warrants that had nothing to do with the stop. Kennedy ultimately did not cooperate with the CCRB. He told ProPublica that with a baby on the way, he did not have time to stay involved with an investigation that he was skeptical of to begin with.

As a result, McCormack was never interviewed by investigators.

On the night of Jan. 30, 2012, Devon Johnson was standing outside a housing project on East 143rd Street in the Bronx when McCormack approached him.

“I know you,” said McCormack, according to a CCRB investigation.

McCormack told investigators he had been involved in arresting Johnson five years before. Johnson had drug and weapons convictions on his record and was under federal investigation for dealing crack cocaine in the projects he was standing in front of.

But even for someone who had dealt a lot with police, what happened next surprised and aggravated Johnson.

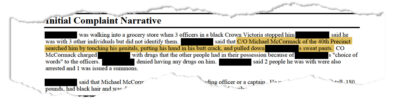

He complained to the CCRB that McCormack unbuttoned and pulled down his pants and searched for drugs, feeling his genitals and anus through his underwear.

“He has me on the floor, pants halfway down,” he said, recalling the event in a recent interview. “He stripped me butt-naked.”

He was not arrested that night. But by the time McCormack sat for an interview with CCRB investigators a year later, Johnson was in federal prison.

In his initial interview with the CCRB, McCormack said that his decision to stop and frisk Johnson was based on a “furtive” action he had observed and that he knew Johnson was a drug dealer. In his second interview, however, McCormack was inconsistent about whether it was his criminal past that influenced his decision to frisk him. At no point did McCormack mention Johnson’s previous weapons charges.

The CCRB determined that McCormack lacked reasonable suspicion at the time that Johnson had committed a crime, and therefore he had no right to stop him or frisk him. Those allegations were substantiated, deemed abuses of authority.

But the allegation that McCormack reached into Johnson’s pants ended like most of the others. Johnson said it happened. McCormack and his partner said it didn’t, and without any additional evidence either way, it went unsubstantiated.

The CCRB decided two other men’s strip-search allegations against McCormack were unfounded. They came to that conclusion once because the alleged search happened in a public place and in broad daylight, suggesting someone would have seen it and said something. The second time, the complainant did not include the allegation in a letter announcing his intent to sue. The allegation was, however, mentioned in later court filings; the city settled the lawsuit for $25,000.

Serrano and Baez would later claim they received low evaluations to punish them for voicing their concerns over McCormack’s orders. They are now suing the NYPD for racial discrimination.

In February 2013, Serrano secretly recorded a long, contentious conversation in which McCormack defended his evaluation. He said Serrano had failed to make enough stops and arrests in a high-crime area, which clearly meant he was a low-performing officer. His activity would be justifiable if he were patrolling Central Park, but he was in the 4-0, where robberies were up 23%.

“We’re still one of the most violent commands in the city,” McCormack told him.

At one point Serrano asked him: “OK. ... So what am I supposed to do? Is it stop every Black and Hispanic?”

McCormack replied: “This is about stopping the right people, the right place, the right location. … Take Mott Haven, where we had the most problems. And the most problems we had there were robberies and grand larcenies.”

When Serrano pressed him further, McCormack said, “The problem was, what? Male Blacks. And I told you at roll call, and I have no problem telling you this: male Blacks, 14 to 20, 21.”

A month later, lawyers suing the city over stop-and-frisk played Serrano’s recording in Manhattan federal court, sending the critical sound bites all over the city. On May 13, 2013, McCormack took the stand and defended himself, saying there had been a spate of robberies in Mott Haven and the perpetrators matched the description he gave Serrano. He said he had never issued quotas.

On Aug. 12, 2013, Judge Shira Scheindlin ruled that the NYPD application of stop-and-frisk violated the constitutional rights of people of color. She noted that while McCormack did “not display the contempt or hostility toward the local population” that she heard in a recording of another officer, his testimony supported her opinion that the “right people” was an indirect form of racial profiling.

“Individuals of all races engage in suspicious behavior and break the law,” she said in her ruling. “Equal protection guarantees that similarly situated individuals of these races will be held to account equally.”

Gabriel De Jesus, the president of the 40th Precinct’s community council, said McCormack’s style was informed by complaints he heard from residents in community board meetings. Several of McCormack’s supporters said the same. “His door was always open,” De Jesus said. “He was also out with his officers, not just in his office. He led by example and people liked that.”

But we spoke to several community leaders in the South Bronx, and they said such meetings can create an unbalanced view of neighborhood needs and concerns.

“If you have an event and you have a whole bunch of cops there, of course, you’re going to hear all the little old ladies,” said Althea Stevens, a director at the East Side House Settlement, an education nonprofit in the South Bronx. “But you didn’t speak to the young people. They’re part of the community.”

Dariella Rodriguez, 40, spent much of her youth in the South Bronx and is now the director of community organizing at The Point, a nonprofit that provides educational and social services in the Hunts Point neighborhood.

She said that she and her friends were often stopped when they came out of school, and her brother would recount being thrown up against buildings by police who aggressively searched him. “It’s not that they got away with it or they hid it or they were sneaky,” she said. “No, they are being rewarded for doing exactly their job and we know that.”

“Being policed like that for so long not only psychologically makes you feel like you’re a bad person, like your community is bad,” said Clarisa Alayeto, who grew up in Mott Haven’s Patterson Houses and is now vice chair of a community board there. “It builds a real bad relationship between us and the Police Department. If you’re someone who’s constantly being stopped and frisked by a police officer, wrongfully, then you know that system is broken. You know that system doesn’t work.”

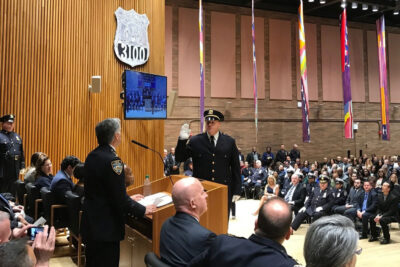

In 2015, McCormack was promoted to full inspector.

Up to the rank of captain, promotions are based almost exclusively on written tests. Sometimes CCRB complaints are considered, but for the most part, a high score will guarantee promotion.

Beyond the rank of captain, promotions are ultimately at the discretion of the police commissioner.

In the past, commissioners have relied on promotion boards to help them evaluate candidates. Chapman, the former deputy commissioner who was once in charge of training, chaired such a panel in 2010. It consisted of five high-ranking officers who gave candidates scores based on how they performed in interviews that covered three areas: technical knowledge, job experience and communications skills. A ranked list was ultimately passed onto the commissioner, who would make the selection.

But Chapman said the rankings really didn’t mean much. On one occasion, a former commissioner selected someone who never even appeared before the panel.

“It is subject to the arbitrary and capricious idiosyncrasies of the mayor and the police commissioner. You might have an all-Irish promotion list or an all-Italian promotion list, or the pressure’s on ‘I’ve got to promote some women and minorities,’” said Chapman, who is Black.

Current and former officers say the most influential factor in advancement comes down to who candidates know. “It’s like a secret society,” said one former high-ranking NYPD officer, adding that family connections are particularly important.

“That type of so-called process for promotion is not at all unusual,” said Walter Katz, vice president of a law enforcement consulting company called Arnold Ventures, which works with police departments across the country on improving their oversight.

“In my experience, past complaints are not at all a factor,” he said. “It signals to the public that the department is not concerned with the public’s opinion and it signals internally that that kind of behavior will not be a detriment to advancement.”

Many officers said complaints are either ignored or weaponized at the whim of the top brass. Several said race plays a role.

“If I’m a minority officer and it’s my turn up, then all of a sudden it matters that when I was a cop 20 years ago, such-and-such happened,” said Anthony Miranda, who retired as an NYPD sergeant and represents roughly 10,000 officers as the CEO of the National Latino Officers Association, a fraternal advocacy group. “Then they say, ‘Well, since you got that on your records, we’re not going to give you that job.’ Then it matters.”

Data shows that while more than half of officers in the lowest rank are people of color, the higher ranks — above captain — are more than 75% white.

A dozen of those high-ranking officers have three or more complaints with substantiated allegations; 10 are white. Five have reached the rank of deputy inspector, the lowest promoted at the commissioner’s discretion; all are white.

“The higher you go up in rank, the more untouchable you are,” said a former Internal Affairs Bureau investigator. “You never see captains or inspectors get hammered or thrown out, even for criminal matters; things a regular cop, or detective, would get fired for, these guys get shielded.”

Jenn Rolnick Borchetta became familiar with McCormack through her work as one of the lead attorneys on the stop-and-frisk case. “There are officers who are wanton and wild with misconduct,” she said. “And those officers the NYPD shuffles around. But then there are officers whose use of aggressive tactics is more of a controlled boil. And those guys get promoted. Those are guys like Chris McCormack.”

McCormack has been accused of misconduct in at least 16 lawsuits, 11 of which settled for a combined $415,000. The allegations ranged from racial discrimination to strip-searches to false arrests.

The city settled three of them in 2016, paying a total of $84,500 to complainants who alleged that McCormack had been involved in improper strip-searches.

That same year, James O’Neill became NYPD commissioner.

McCormack and O’Neill went way back. They worked together in the Bronx and in executing warrants across the city. They also shared two CCRB complaints in 1997. In one, a complainant said one of the officers in their squad threatened to “rip [his] testicles off.” The man was not arrested, and the CCRB substantiated several abuse allegations in the complaint, involving his detention and search. It did not specify the name of the officer who made the threat, but all involved wound up with a finding of misconduct.

Years later, a former cop and commenter on the police blog Thee Rant admired McCormack in a post that referred to him as “O’Neill’s unruly son” and speculated that he, too, might one day become commissioner.

ProPublica attempted to reach O’Neill several times, but he did not respond to text messages or phone calls.

Many current and former high-ranking NYPD officers believe McCormack’s relationship with O’Neill was key to his promotions.

“Chris is a hard worker, but he has been accused of many things in his career,” said an NYPD precinct commander who was not authorized to speak publicly on the matter. He was one of two department veterans who accurately guessed on their first attempt that McCormack was the highest ranking officer with the most substantiated CCRB complaints against him.

“If he wasn’t good friends with O’Neill,” he said, “they would have held him back.”

Instead, in 2017, McCormack became a deputy chief.

The year after that, he rose another rank to assistant chief.

Derek Willis contributed reporting.

About the Data

ProPublica relied on multiple sets of data and records to report this story. On July 26, ProPublica published a searchable Civilian Complaint Review Board database that contained the 12,056 closed complaints of every active-duty police officer who had at least one substantiated allegation against them. Those records span September 1985 to January 2020.

The allegation counts in this story differ from those reported in ProPublica’s database, because the organization had access to a broader set of records than was published.

Through a seperate Freedom of Information Law request, ProPublica obtained a larger set of records for McCormack. Those records include complaints that had been withdrawn or where the complainant was uncooperative. Reporters also obtained a separate trove of CCRB investigative files that examined complaints made specifically against him. These documents were the source of some of the incidents of people quoted in this story.

On Aug. 25, the New York Civil Liberties Union published its own, larger database of CCRB records, which we also analyzed. According to the NYCLU website:

The NYPD Misconduct Complaint Database is a repository of complaints made by the public on record at the Civilian Complaint Review Board (CCRB). These complaints span two distinct periods: the time since the CCRB started operating as an independent city agency outside the NYPD in 1994 and the prior period when the CCRB operated within the NYPD. The database includes 323,911 unique complaint records involving 81,550 active or former NYPD officers. The database does not include pending complaints for which the CCRB has not completed an investigation as of July 2020.

Tell Us About Police Misconduct

Do you have information about an incident? We want to hear from police officers, public employees and community members who can help us learn more.